Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

Q: Did you all see the racist imagery on the cards from the game Ace of Spades?

~Jchon B.

Grand Rapids, Mi

A: Recently a company named Devir debuted a game called The Ace of Spades at the 2025 GenCon Indy convention in Indianapolis. The game received immediate backlash

because of some of the imagery and representations on some of the cards. The company

acted swiftly after the complaints arose and made a public statement, stopped sales of the game, offered replacement cards, and removed “all social media

content related to the game until all materials were reviewed and revised.”

A: Recently a company named Devir debuted a game called The Ace of Spades at the 2025 GenCon Indy convention in Indianapolis. The game received immediate backlash

because of some of the imagery and representations on some of the cards. The company

acted swiftly after the complaints arose and made a public statement, stopped sales of the game, offered replacement cards, and removed “all social media

content related to the game until all materials were reviewed and revised.”

On social media, the reaction has been mixed. Some are in support of the pulling of the game and see the problems with the imagery, while others do not see the issues with the illustrations. There are some who believe the apology from Devir misses the mark because they only admitted to two of the cards being “inappropriate illustrations” and “trivializ(ing)” the “violence and trauma of slavery.” Devir has not of yet addressed some of the other problematic cards.

Using imagery of the enslavement period is not necessarily wrong, but context is key. And it appears the game lacks context. One of the lessons that is often taught at the Jim Crow Museum is to understand the imagery of the past, so that we recognize its negative impact, and therefore not reproduce the same type of imagery, especially if it is not in context. We say at the museum all the time, that someone in the room making decisions about these types of portrayals should have stood up and objected to the proposed offensive imagery.

Let us look at some of the images on the cards and see their relationship with images and representations of the past and why they are problematic. The first thing to note, is that all the cards in question are considered “enemy cards” or “villains” and the game’s theme is based in the “Wild West.” After you defeat the “enemy” or “villain,” you gain a power described at the bottom of the card for the next rounds.

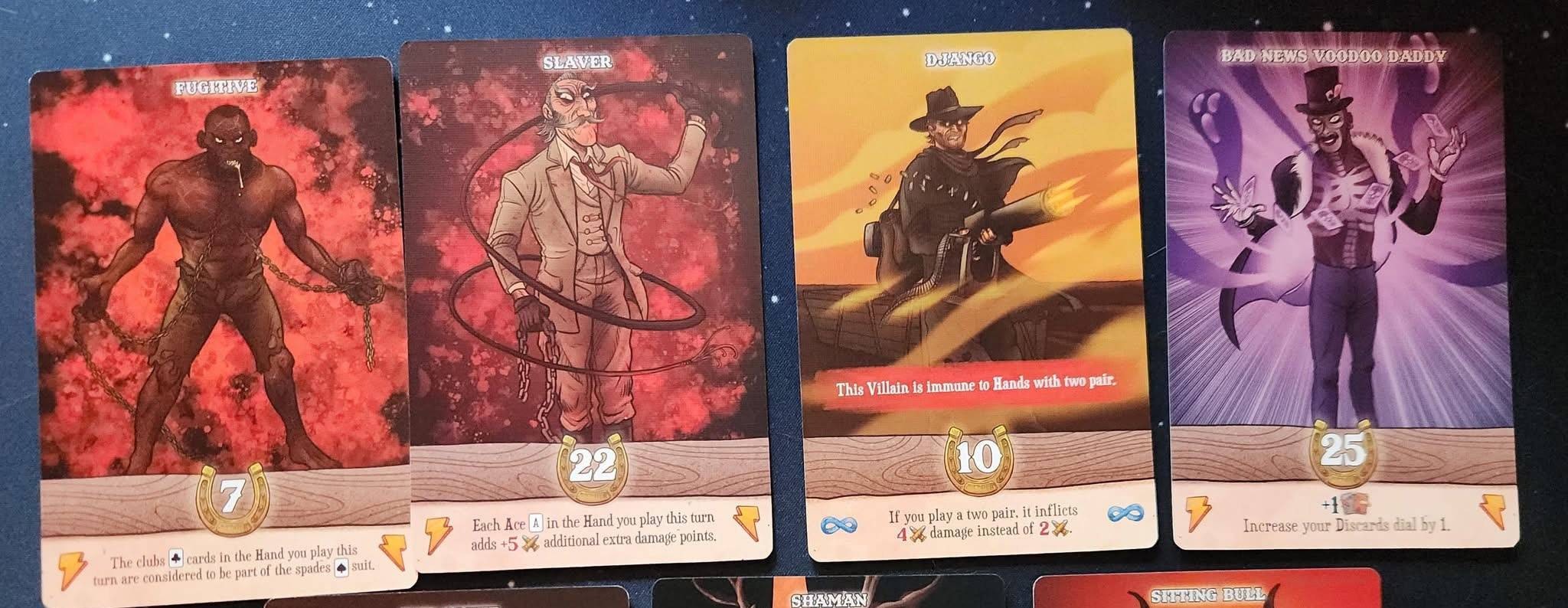

The Fugitive villain card.

The Fugitive villain card. The Fugitive card clearly depicts an ethnic African runaway enslaved man. The Fugitive is shirtless and barefoot with tattered short pants and holding broken chains that are affixed to a neck shackle. Probably the most disturbing aspect about the imagery is that the “fugitive” appears to be growling and foaming at the mouth. The card uses elements of the brute caricature. One of the narratives toward the end of the enslavement period and directly afterward, was that black men were “innately savage, animalistic, destructive, and criminal.” This narrative was used to justify the enslavement of black people. Dr. David Pilgrim writes:

“During the Radical Reconstruction period (1867-1877), many white writers argued that without slavery -- which supposedly suppressed their animalistic tendencies -- black people were reverting to criminal savagery. The belief that the newly-emancipated black people were a "black peril" continued into the early 1900s.” (Pilgrim, 2000)

The Brute villain card would also fit into the brute stereotype and caricature. The card depicts a brown skinned man who is very strong with a menacing scowl and is at the ready to pull out the pistols at his side while wearing a large sombrero. Although the character depicted is probably of a person with Latino heritage, many Latinos were subjected to similar discrimination laws and treatment as African Americans. There were hundreds of segregations signs, especially in the West and in the Southwest that stated, “No Dogs, Negros, Mexicans” or signs that said, “We serve white’s only, No Spanish or Mexicans.” These beliefs justified the imprisonment and lynching of people of color during the Jim Crow era. In the book Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence Against Mexicans in the United States 1848-1928 by Clive Webb and William D. Carrigan, the authors explore the hundreds and probably thousands of Mexicans murdered by mobs during that period.

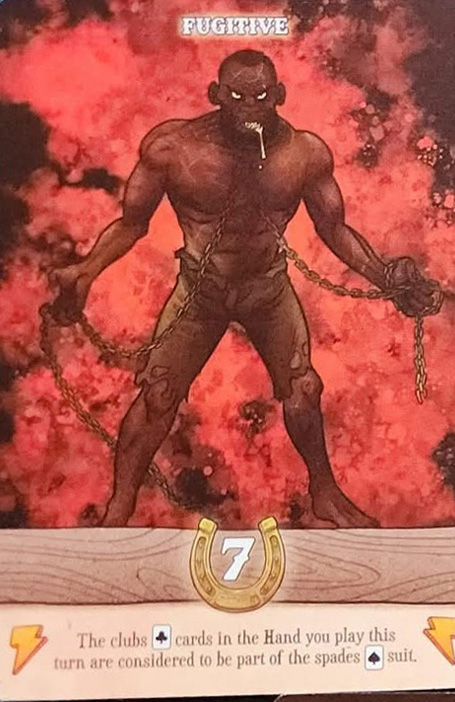

To be honest, this is the only “enemy” card that probably should be considered a “villain.” The Slaver is portrayed as a white man wearing a 1850s style suit holding a broken chain (which perhaps is associated with the Fugitive’s broken chains) and loading up a whip for a strike. The image of the Slaver on the card resembles the many illustrations and depictions of the character Simon Legree from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The atrocities of the enslavement period should not be trivialized nor sensationalized for effect.

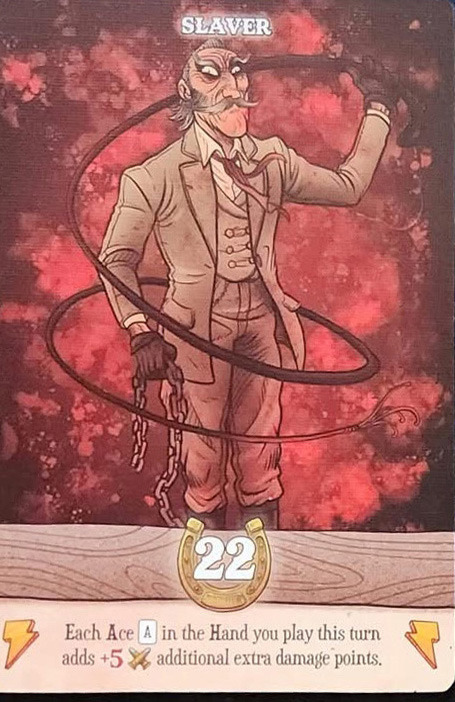

In the Devir apology response, it was stated that the some of the illustrations “were originally intended as visual references to scenes from the film Django Unchained, as part of the game’s homage to Western cinema.” Apparently, the homage was to the 1966 film version where the protagonist was played by Italian actor Franco Nero and not the 2012 version featuring Jamie Foxx as Django. The card depicts Django as a white man dressed like the 1966 film Django and shooting an iconic machine gun from the movie. Again, it is interesting that an apparent protagonist in the Django film, is considered a villain in the Ace of Spades game. The 1966 film had little to do with the American slavery period, it was more of a “spaghetti Western,” so it is unclear what homage is being paid other than the imagery on the card and furthermore, how is the Fugitive, the Slaver, the Shaman, and the Bad News Voodoo Daddy related to the 1966 film?

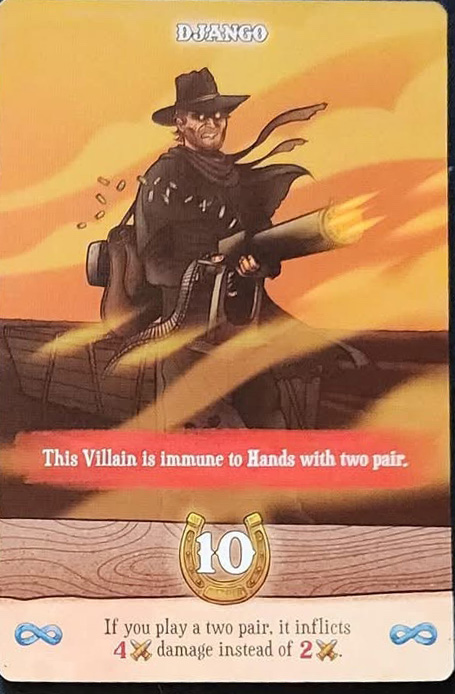

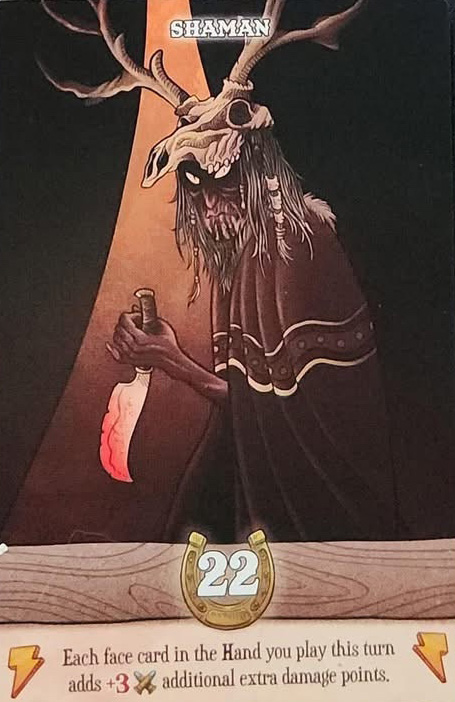

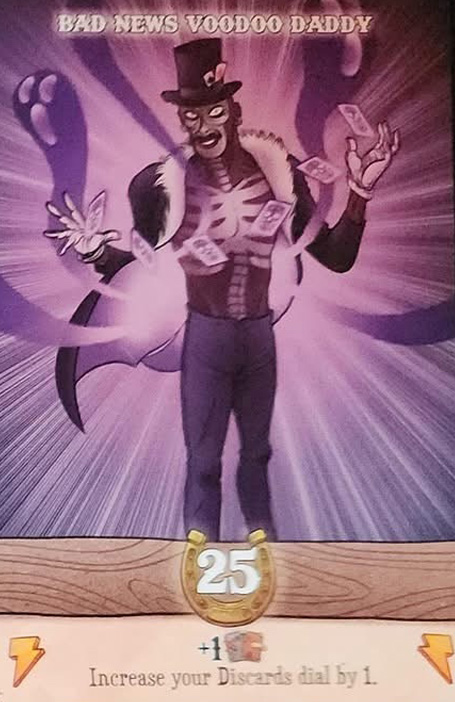

The Shaman villain card and the Bad News Voodoo Daddy villain card.

The Shaman villain card and the Bad News Voodoo Daddy villain card. These two cards have a few elements that are consistent with negative stereotypes, caricatures, and tropes of black people such as witchdoctors and cannibals.

The savage caricature often shows Africans and other “natives” as animalistic, crazed, or comical cannibals, often with bones in their lips. In many comic books, cartoons, and movies of the Jim Crow era, the savage caricature is depicted as a Shaman or witchdoctor who leads a group of cannibals, usually while they chase, catch and bind, place in a big black caldron, and subsequently eat their white victims. The trope is also based somewhat on the belief that African culture is steeped in Voodoo and dark magic. The Shaman villain card depicts a black character with an animal skull on its head, dark threatening eyes, in a robe, and holding a blood-stained knife.

The Voodoo trope is based on the idea that a priest or priestess, (usually a black

priest or priestess from the Caribbean or Louisiana), has magic abilities, uses tarot

cards, and conjures spirits from the underworld. The Bad News Voodoo Daddy villain

card matches the trope’s characteristics with a top hat, a skull painted face and

body, and floating tarot cards.

The Voodoo trope is based on the idea that a priest or priestess, (usually a black

priest or priestess from the Caribbean or Louisiana), has magic abilities, uses tarot

cards, and conjures spirits from the underworld. The Bad News Voodoo Daddy villain

card matches the trope’s characteristics with a top hat, a skull painted face and

body, and floating tarot cards.

For more information about the Voodoo and witchdoctor trope, see Graphic Voodoo: Africana Religion in Comics and Voodoo Tropes: Bizarre Hollywood Religion by Professor Yvonne Chireau.

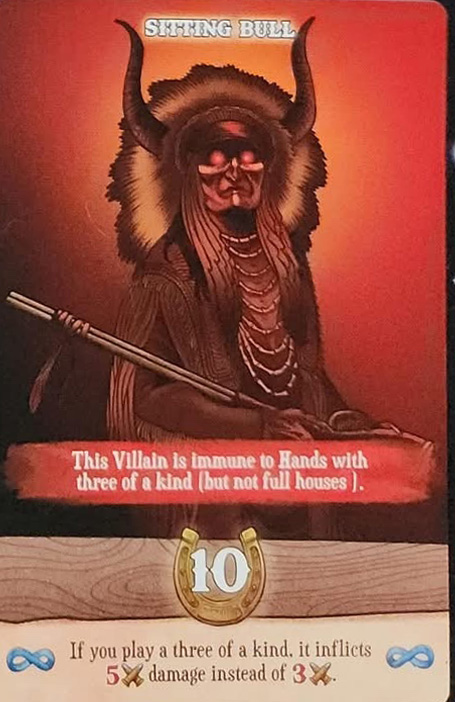

The Sitting Bull villain card.

The Sitting Bull villain card.Although the Jim Crow Museum does not primarily focus on imagery about Native Americans, the museum does have quite a large collection on display at the current facility. In 2018, two scholars, Arlene Hirschfelder and Paulette F. Molin, expounded our Native American stereotypes narratives by writing the article I is for Ignoble: Stereotyping Native Americans.

Unlike the previous cards, the Sitting Bull villain card is based on an historical figure. Sitting Bull was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader, both militarily and spiritually, and widely known for the Battle of Little Bighorn where the native warriors defeated General Custer and his army in less than an hour. Months before the battle, Sitting Bull led the Lakota in a Sundance ritual where he had visions of a great victory for the tribe. These visions inspired the warriors and is credited as the driving force for their victory.

The Sitting Bull villain card from the Ace of Spades game depicts Sitting Bull as a military leader with a warrior headdress, his eyes are red as if in a trance or seeing a vision and he is holding a traditional ceremonial pipe in his right hand. Even though this characterization of Sitting Bull is not entirely bad, why is he considered an “enemy” or a “villain” in the game? Sitting Bull and the Lakota were eventually forced off their land and many retreated to Canada. Facing starvation in Canada, Sitting Bull and his people would eventually return to the United States. Sitting Bull would later travel with the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. In 1890 he was accused of leading a Native uprising and was shot and killed during an attempted arrest.

As you can see, there were a number of problematic cards in the game, not just the ones associated with slavery. It is good that Devir has taken steps to correct the errors, but it is still hard to believe that the game made it all the way to production, which must have included play testing with multiple people, and these stereotypical depictions were not addressed. Devir is a successful worldwide game publisher. It is our duty, as well as theirs, to understand the importance of imagery and representation.

The Jim Crow Museum would love to have an original copy of the game so that we could have these discussions about race and representation with our patrons. We would also love to host members of Devir’s staff to continue the discussion. The tagline of the Jim Crow Museum is to Witness, Understand, Heal and we are hopeful we can help people get through all three phases.

Franklin Hughes

Jim Crow Museum

2025

References

Ace of Spades correction. (2025). https://devirgames.com/announcement-about-the-game-ace-of-spades

Chireau, Y., (2016, November 25). Graphic Voodoo: Africana religion in comics. AAIHS - African American Intellectual History Society. https://www.aaihs.org/graphic-voodoo-africana-religion-in-comics/

Chireau, Y. (2013, September). Voodoo Tropes: Bizarre Hollywood religion. Professor Chireau’s Academic Hoodoo. https://academichoodoo.com/2013/09/12/voodoo-tropes-2-bizarre-hollywood-religion/

Hirschfelder, A., & F. Molin, P. (2018, February 22). I is for Ignoble: Stereotyping Native Americans. The Jim Crow Museum. https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/native/homepage.htm

Pilgrim, D. (2000). The Brute Caricature - Jim Crow Museum. https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/brute/homepage.htm

Webb, C., & D. Carrigan, W. (2013). Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence against Mexicans in the United States, 1848–1928. Oxford University Press