Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

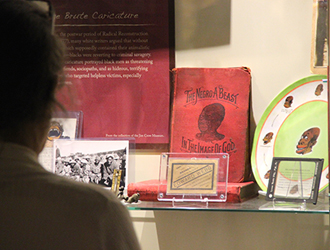

The brute caricature portrays black men as innately savage, animalistic, destructive, and criminal -- deserving punishment, maybe death. This brute is a fiend, a sociopath, an anti-social menace. Black brutes are depicted as hideous, terrifying predators who target helpless victims, especially white women. Charles H. Smith (1893), writing in the 1890s, claimed, "A bad negro is the most horrible creature upon the earth, the most brutal and merciless"(p. 181). Clifton R. Breckinridge (1900), a contemporary of Smith's, said of the black race, "when it produces a brute, he is the worst and most insatiate brute that exists in human form" (p. 174).

George T. Winston (1901), another "Negrophobic" writer, claimed:

When a knock is heard at the door [a White woman] shudders with nameless horror. The black brute is lurking in the dark, a monstrous beast, crazed with lust. His ferocity is almost demoniacal. A mad bull or tiger could scarcely be more brutal. A whole community is frenzied with horror, with the blind and furious rage for vengeance.(pp. 108-109)

During slavery the dominant caricatures of black people -- Mammy, Coon, Tom, and picaninny -- portrayed them as childlike, ignorant, docile, groveling, and generally harmless. These portrayals were pragmatic and instrumental. Proponents of slavery created and promoted images of black people that justified slavery and soothed white consciences. If slaves were childlike, for example, then a paternalistic institution where masters acted as quasi-parents to their slaves was humane, even morally right. More importantly, slaves were rarely depicted as brutes because that portrayal might have become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

During the Radical Reconstruction period (1867-1877), many white writers argued that without slavery -- which supposedly suppressed their animalistic tendencies -- black people were reverting to criminal savagery. The belief that the newly-emancipated black people were a "black peril" continued into the early 1900s. Writers like the novelist Thomas Nelson Page (1904) lamented that the slavery-era "good old darkies" had been replaced by the "new issue" (black people born after slavery) whom he described as "lazy, thriftless, intemperate, insolent, dishonest, and without the most rudimentary elements of morality" (pp. 80, 163). Page, who helped popularize the images of cheerful and devoted Mammies and Sambos in his early books, became one of the first writers to introduce a literary black brute. In 1898 he published Red Rock, a Reconstruction novel, with the heinous figure of Moses, a loathsome and sinister black politician. Moses tried to rape a white woman: "He gave a snarl of rage and sprang at her like a wild beast" (pp. 356-358). He was later lynched for "a terrible crime."

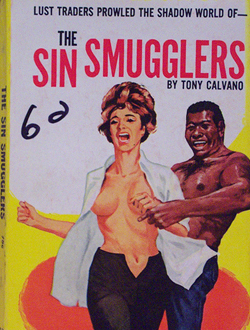

The "terrible crime" most often mentioned in connection with the black brute was rape, specifically the rape of a white woman. At the beginning of the twentieth century, much of the virulent, anti-black propaganda that found its way into scientific journals, local newspapers, and best-selling novels focused on the stereotype of the black rapist. The claim that black brutes were, in epidemic numbers, raping white women became the public rationalization for the lynching of black people.

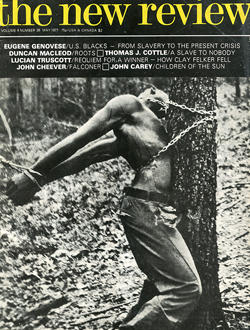

The lynching of black people was relatively common between Reconstruction and World War II. According to Tuskegee Institute data, from 1882 to 1951 4,730 people were lynched in the United States: 3,437 black and 1,293 white (Gibson, n.d.). Many of the white lynching victims were foreigners or belonged to oppressed groups, for example, Mormons, Shakers, and Catholics. By the early 1900s lynching had a decidedly racial character: white mobs lynched black people. Almost 90 percent of the lynchings of black people occurred in southern or border states.

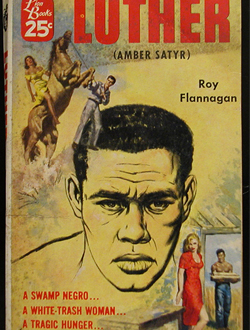

Many of these victims were ritualistically tortured. In 1904, Luther Holbert and his wife were burned to death. They were "tied to trees and while the funeral pyres were being prepared, they were forced to hold out their hands while one finger at a time was chopped off. The fingers were distributed as souvenirs. The ears...were cut off. Holbert was beaten severely, his skull fractured and one of his eyes, knocked out with a stick, hung by a shred from the socket." Members of the mob then speared the victims with a large corkscrew, "the spirals tearing out big pieces of...flesh every time it was withdrawn" (Holden-Smith, 1996, p. 1).

A mob lynching was a brutal and savage event, and it necessitated that the lynching victim be seen as equally brutal and savage; as these lynchings became more common and more brutal, so did the assassination of the black character. In 1900, Charles Carroll's The Negro A Beast claimed that black people were more akin to apes than to human beings, and theorized that black people had been the "tempters of Eve." Carroll said that mulatto1 brutes were the rapists and murderers of his time (pp. 167, 191, 290-202). Dr. William Howard, writing in the respectable journal Medicine in 1903, claimed that "the attacks on defenseless White women are evidence of racial instincts" (in black people), and the black birthright was "sexual madness and excess" (Fredrickson, 1971, p. 279). Thomas Dixon's The Leopard's Spots, a 1902 novel, claimed that emancipation had transformed black people from "a chattel to be bought and sold into a beast to be feared and guarded" (Fredrickson, p. 280).

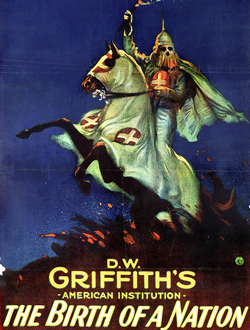

In 1905 Dixon published his most popular novel, The Clansman. In this book he described black people as "half child, half animal, the sport of impulse, whim, and conceit...a being who, left to his will, roams at night and sleeps in the day, whose speech knows no word of love, whose passions, once aroused, are as the fury of the tiger" (Fredrickson, 1971, pp. 280-281). The Clansman includes a detailed and gory account of the rape of a young white virgin by a black brute. "A single tiger springs, and the black claws of the beast sank into the soft white throat." After the rape, the girl and her mother both commit suicide, and the black brute is lynched by the Ku Klux Klan. This book served as the basis for the movie The Birth of a Nation (Griffith, 1915), which also portrayed some black people as rapist-beasts, justified the lynching of black people, and glorified the Ku Klux Klan. Carroll, Howard, and Dixon did not exceed the prevailing racism of the so-called Progressive Era.

In 1921-22 the United States House of Representatives and Senate debated the Dyer Bill, an anti-lynching bill. This bill provided fines and imprisonment for persons convicted of lynching in federal courts, and fines and penalties against states, counties, and cities which failed to use reasonable effort to protect citizens from lynch mobs. The Dyer Bill passed in the House of Representatives, but it was killed in the Senate by filibustering southerners who claimed that it was unconstitutional and an infringement upon states' rights (Gibson, n.d., p. 5). The following statements made by southern Congressmen during the Dyer Bill debate suggest that they were more concerned with white supremacy and the oppression of black people than they were with constitutional issues.

Senator James Buchanan of Texas claimed that in "the Southern States and in secret meetings of the Negro race [white liberals] preach the damnable doctrine of social equality which excites the criminal sensualities of the criminal element of the Negro race and directly incites the diabolical crime of rape upon the white women. Lynching follows as swift as lightning, and all the statutes of State and Nation cannot stop it." (Holden-Smith, 1996, p. 14)

Representative Percy Quin of Mississippi, spoke of lynch law, "Whenever an infamous outrage is committed upon a [Southern] White woman the law is enforced by the neighbors of the woman who has been outraged? The colored people of [the South] realize the manner of that enforcement, and that is the one method by which the horrible crime of rape has been held down where the Negro element is in a large majority. The man who believes that the Negro race is all bad is mistaken. But you must recollect that there is an element of barbarism in the black man, and the people around where he lives recognize that fact." (Holden-Smith, 1996, p. 15)

Representative Sisson of Mississippi said, "as long as rape continues lynching will continue. For this crime, and this crime alone, the South has not hesitated to administer swift and certain punishment....We are going to protect our girls and womenfolk from these black brutes. When these black fiends keep their hands off the throats of the women of the South then lynching will stop..." (Holden-Smith, 1996, p. 16)

Representative Benjamin Tillman from South Carolina claimed that the Dyer Bill would eliminate the states and "substitute for the starry banner of the Republic, a black flag of tyrannical centralized government...black as the face and heart of the rapist...who [recently] deflowered and killed Margaret Lear," a White girl in South Carolina. (Holden-Smith, 1996, p. 14) Tillman asked why anyone should care about the "burning of an occasional ravisher," when the House had more important concerns. (Holden-Smith, 1996, p. 16)

Senator T.H. Caraway of Arkansas claimed that the NAACP, "wrote this bill and handed it to the proponents of it. These people had but one idea in view, and that was to make rape permissible, and to allow the guilty to go unpunished if that rape should be committed by a Negro against a white woman in the South." (Holden-Smith, 1996, p. 16)

Despite the hyperbolic claims of those Congressmen, most of the black people lynched had not been accused of rape or attempted rape. According to the Tuskegee Institute's lynching data, the accusations against lynching victims for the years 1882 to 1951 were: 41 percent for felonious assault, 19.2 percent for rape, 6.1 percent for attempted rape, 4.9 percent for robbery and theft, 1.8 percent for insulting white people, and 27 percent for miscellaneous offenses (for example, trying to vote, testifying against a white man, asking a white woman to marry) or no offenses at all (Gibson, n.d., p. 3). The 25.3% who were accused of rape or attempted rape were often not guilty, and were killed without benefit of trial. Gunnar Myrdal (1944), a Swedish social scientist who studied American race relations, stated:

There is much reason to believe that this figure [25.3 percent] has been inflated by the fact that a mob which makes the accusation of rape is secure from any further investigation; by the broad Southern definition of rape to include all sexual relations between Negro men and white women; and by the psychopathic fears of white women in their contacts with Negro men. (pp. 561-562)

Lynchings often involved castration, amputation of hands and feet, spearing with long nails and sharpened steel rods, removal of eyes, beating with blunt instruments, shooting with bullets, burning at the stake, and hanging. It was, when done by southern mobs, especially sadistic, irrespective of the criminal charge. Most white southerners agreed that lynching was evil, but they claimed that black brutes were a greater evil.

Lynchings were necessary, argued many white people, to preserve the racial purity of the white race, more specifically, the racial purity of white women. White men had sexual relations -- consensual and rape -- with black women as soon as Africans were introduced into the European American colonies. These sexual unions produced numerous mixed-race offspring. White women, as "keepers of white racial purity," were not allowed consensual sexual relations with black men. A black man risked his life by having sexual relations with a white woman. Even talking to a white woman in a "familiar" manner could result in black males being killed.

In 1955, Emmett Till, a black fourteen year old from Chicago, visited his relatives in Mississippi. The exact details are not known, but Till apparently referred to a female white store clerk as "Baby." Several days later, the woman's husband and brother took Till from his uncle's home, beat him to death -- his head was crushed and one eye was gouged out--and threw his body into the Tallahatchie River. The men were caught, tried, and found innocent by an all-white jury. The case became a cause celebre during the civil rights movement, showing the nation that brutal violence undergirded Jim Crow laws and etiquette.

There were black rapists with white victims, but they were relatively rare; most white rape victims were raped by white men. The brute caricature was a red herring, a myth used to justify lynching, which in turn was used as a social control mechanism to instill fear in black communities. Each lynching sent messages to black people: Do not register to vote. Do not apply for a white man's job. Do not complain publicly. Do not organize. Do not talk to white women. The brute caricature gained in popularity whenever black people pushed for social equality. According to Allen D. Grimshaw (1969), a sociologist, the most savage oppression of black people by white people, whether expressed in rural lynchings or urban race riots, has taken place when black people have refused or been perceived by white people as refusing to accept a subordinate or oppressed status (pp. 264-265).

The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s forced many white Americans to examine their images of and beliefs about black people. Television and newspaper coverage showing black protesters, including children, being beaten, arrested, and jailed by baton-waving police officers led many white people to see black people as victims, not victimizers. The brute caricature did not die, but it lost much of its credibility. Not surprisingly, lynchings, especially public well-attended ones, decreased in number. Lynchings became "hate crimes," committed secretly. Beginning in the 1960s the relatively few black people who were lynched were not accused of sexual assaults; instead, these lynchings were reactions of white supremacists to black economic and social progress.

The brute caricature has not been as common as the Coon caricature in American movies. The Birth of a Nation (Griffiths, 1915) was the first major American movie to portray all the major anti-black caricatures, including the brute. That movie led to numerous black protests and white-initiated race riots. One result of the racial strife was that black male actors in the 1920s through 1940s found themselves limited to Coon and Tom roles. It was neither socially acceptable nor economically profitable to show movies where black brutes terrorized white people.

In the 1960s and 1970s "Blaxploitation" movies brought aggressive, anti-white black males onto the big screen. Some of these fit the "Buck" caricature -- for example, the private detective in Shaft (Freeman & Parks, 1971) and the pimp in Superfly (Shore & Parks, 1972) -- but some of the Blaxploitation actors were cinematic brutes, for example Melvin Van Peebles' character in Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song (Gross, Van Peebles & Van Peebles, 1971). Sweetback, the main character, is falsely accused of a crime. On the lam he assaults several men, rapes a black woman, and kills corrupt police officers. The movie ends with the message: A BAADASSSSS NIGGER IS COMING BACK TO COLLECT SOME DUES. That frightened white people. Young black people, tired of the Stepin Fetchit portrayals, flocked to see the low-budget movie. Although dressed in the clothes of a rebel, Sweetback was as much a brute as had been the lustful Gus in The Birth of a Nation.

American Gigolo (Bruckheimer & Schrader, 1980) had a poisonous and despicable black pimp. He was one of the many black sadistic pimps who have abused and degraded white people in American movies. Mister---, the husband in The Color Purple (Jones, Kennedy, Marshall, Spielberg & Spielberg, 1985), is an angry and savage wife abuser, and so is Ike Turner in What's Love Got To Do With It? (Chapin, Krost & Gibson, 1993). Both are brutes whose victims happen to be black. Turner's real life criminal behavior (which predated the movie) was used to give credibility to his character's portrayal as a brute and, more importantly, to reinforce the belief that black people are especially prone to brutish behavior.

In the 1980s and 1990s the typical cinema and television brute was nameless and sometimes faceless; he sprang from a hiding place, he robbed, raped, and murdered. He represented the cold brutality of urban life. Often he was a gangbanger. Sometimes he was a dope fiend. Actors who played the black brute were usually not on screen very long, just long enough to terrorize innocent victims. They were movie props. On television shows like Law and Order, Homicide: Life on the Streets, ER, and NYPD Blue, nameless black brutes assault, maim, and kill. On October 2, 2000, NBC debuted Deadline, a drama involving an irascible journalism teacher. In the first episode two young black males brutally kill five restaurant workers. They kill without remorse.

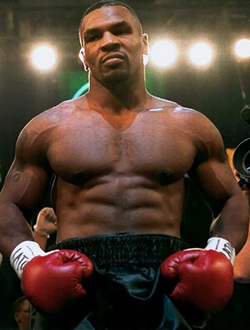

The recent depiction of black males as brutes is not limited to television dramas. Mike Tyson, the former heavyweight boxing champion, has embraced the brute image. Tyson was marketed as a sadistic and savage warrior who was capable of killing an opponent. His quick knockouts bolstered his reputation as the world's most feared man. Joyce Carol Oates wrote, "Tyson suggests a savagery only symbolically contained within the brightly illuminated ring" (Souther, n.d.). She wrote this a decade before Tyson was convicted of several criminal charges, including the rape of a beauty pageant contestant, and later, the battering of two motorists. After his boxing skills had diminished, Tyson gained greater notoriety by biting the ear of an opponent during a bout. In a news conference Tyson said, "I am an animal. I am a convicted rapist, a hell-raiser, a loving father, a semi-good husband." Referring to Lennox Lewis, the heavyweight boxing champion, Tyson said, "If he ever tries to intimidate me, I'm gonna put a fu--ing bullet through his fu--ing skull" (Serjeant, 2000). Tyson benefited from the brute image. His boxing matches were "events." Spectators paid thousands of dollars for ringside seats. Tyson became the wealthiest and best known athlete on earth. In his mind, he was a twenty-first century gladiator; to the American public, he was simply a black brute.

Tyson is a violent and emotionally unstable man, but he is more than a one-dimensional brute. He has donated thousands of dollars to civic, educational, and humanitarian organizations. Without media fanfare, he has visited hundreds of hospitalized patients, especially seriously ill and injured children. He is smarter than his public image, and has worked diligently to "deepen" his intellect. Yet, he was marketed, with his permission, as a crude savage. Americans see him as an affirmation of the black brute caricature, and he has, especially in recent years, embraced the stereotype outside the boxing ring. Tyson can no longer distinguish the (Iron Mike) myth from the (vicious criminal) madness, and many white Americans cannot separate Tyson's criminal behavior from his blackness.

During the 1988 presidential campaign, George Bush's election committee sought to portray his opponent, Michael Dukakis, as weak on crime. Bush's team used television advertisements which showed a menacing mug shot of Willie Horton, a black convicted murderer. Horton, while out of prison on an unguarded 48-hour furlough, kidnapped a young white suburban couple. He repeatedly stabbed the man and raped the woman several times. The image of Horton's threatening face on the nation's television screens helped Bush win the election. It also reinforced the belief that a black brute is worse than a white brute.

My wife's been shot. I'm shot.... He made us go to an abandoned area. I don't see any signs. Oh, God!

This frantic telephone call came into the Massachusetts State Police on the night of October 23, 1989. After a desperate search, using only the sound from the open cell telephone as their guide, police discovered an injured couple. Carol DiMaiti Stuart, seven months pregnant, had been shot in the head; Charles, her husband, had a serious gunshot wound to the abdomen. Hours later, doctors performed a Cesarean section on the dying woman and delivered a premature baby boy who died days later. Charles Stuart told the police that the murderer was a black man.

The city of Boston, which has a history of racial discord, experienced heightened racial tensions as police searched for the black brute. Officers went into black neighborhoods and rounded up hundreds of black men for questioning. The black community was outraged. Charles Stuart picked Willie Bennett out of a lineup; Bennett was subsequently arrested for the crime (Ogletree, n.d.).

Later, police were informed by Stuart's brother that Charles Stuart probably killed his wife for insurance money. The police began investigating Charles Stuart and were building a strong circumstantial case when, on January 4, 1990, he committed suicide.

In 1994 Susan Smith, a young mother in Union, South Carolina, claimed that a man had commandeered her car with her two boys: 14-month-old Alex and 3-year-old Michael. She described the carjacker as a "black male in his late 20s to early 30s, wearing a plaid shirt, jeans, and a toboggan-type hat." A composite of her description was published in newspapers, nationally and locally. Smith appeared on national television, tearfully begging for her sons to be returned safely. An entire nation wept with her, and the image of the black brute resurfaced. The Reverend Mark Long, the pastor of the church where Smith's family attended services, said in reference to the black suspect, "There are some people that would like to see this man's brains bashed in" (Squires, 1994).

After nine days of a gut-wrenching search and strained relations between local black and white people, there was finally a break in the case: Susan Smith confessed to drowning her own sons. In a two-page handwritten confession she apologized to her sons, but she did not apologize to black people, nationally or locally. "It was hard to be black this week in Union," said Hester Booker, a local black man. "The whites acted so different. They wouldn't speak (to blacks); they'd look at you and then reach over and lock their doors. And all because that lady lied" (Fields, 1994).

The false allegations of Charles Stuart and Susan Smith could have led to racial violence. In 1908, in Springfield, Illinois, Mabel Hallam, a white woman, falsely accused "a black fiend," George Richardson, of raping her. Her accusations angered local white people. They formed a mob, killed two black people chosen randomly, then burned and pillaged the local black community. Black people fled to avoid a mass lynching. Hallam later admitted that she lied about the rape to cover up an extramarital affair.

How many lynchings and race riots have resulted from false accusations of rape and murder leveled against so-called black brutes?

© Dr. David Pilgrim, Professor of Sociology

Ferris State University

Nov., 2000

Edited 2023

1 The tragic mulatto caricature was sometimes treated as an adult; albeit, a troubled, white-identified, self-loathing adult.

References

Breckinridge, C. R. (1900). Speech of the Honorable Clifton R. Breckinridge: In Southern Society for the Promotion of the Study of Race Conditions and Problems in the South, Race Problems of the South: Report of the proceedings of the first annual conference held under the auspices of the Southern Society for the Promotion of the Study of Race Conditions and Problems in the South, at Montgomery, Alabama, May 8, 9, 10, A.D. 1900. Richmond, VA: B. F. Johnson Pub. Co.

Bruckheimer, J. (Producer), & Schrader, P. (Director). (1980). American gigolo [Motion picture]. United States: Paramount Pictures.

Carroll, C. (1900). "The Negro a beast"; or, "In the image of God". St. Louis, MO: American Book and Bible House.

Chapin, D., & Krost, B. (Producers), & Gibson, B. (Director). (1993). What's love got to do with it [Motion picture]. United States: Touchstone Pictures.

Dixon, T. (1905). The clansman: an historical romance of the Ku Klux Klan. New York, NY: Grosset & Dunlap.

Dixon, T. (1902). The leopard's spots; a romance of the white man's burden - 1865-1900. New York, NY: Grosset & Dunlap.

Fields, R. (1994, November 4). Black residents hurt, angered. The Herald-Journal (Spartenberg S.C.). Retrieved from http://jclass.umd.edu/archive/newshoax/casestudies/crime/CrimeSmith1104c.html.

Fredrickson, G. M. (1971). The black image in the white mind: The debate on Afro-American character and destiny, 1817-1914. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Freeman, J. (Producer), & Parks, G. (Director). (1971). Shaft [Motion picture]. United States: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Gibson, R.A. (n.d.).The Negro holocaust: Lynching and race riots in the United States, 1890-1950. New Haven, CT: Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute. Retrieved from http://www.yale.edu/ynhti/curriculum/units/1979/2/79.02.04.x.html.

Griffith, D. W. (Producer/Director). (1915). The birth of a nation [Motion picture]. United States: David W. Griffith Corp.

Grimshaw, A. D. (Ed.) (1969). Racial violence in the United States. Chicago, IL: Aldine Pub. Co.

Gross, J., & Van Peebles, M. (Producers), & Van Peebles, M. (Director). (1971). Sweet Sweetback's baadasssss song [Motion picture]. United States: Yeah.

Holden-Smith, B. (1996). Lynching, federalism, and the intersection of race and gender in the Progressive era. Yale Journal of Law and Feminism. Retrieved from http://library2.lawschool.cornell.edu/hein/Holden-Smith,%20Barbara%208%20Yale%20J.L.%20&%20Feminism%2031%201996.pdf.

Jones, Q., Kennedy, K., Marshall, F., & Spielberg, S. (Producers), & Spielberg, S. (Director).The color purple [Motion picture]. United States: Warner Bros. Pictures.

Myrdal, G. (1944). An American dilemma: the Negro problem and modern democracy. New York, NY: Harper.

Ogletree, C. (n.d.) The Basic Black Forum with Charles Ogletree.

Page, T. N. (1898). Red Rock: A chronicle of Reconstruction. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons.

Page, T. N. (1904). The Negro: The southerner's problem. New York, NY: C. Scribner's Sons.

Shore, S. (Producer), & Parks, G. Jr. (Director). (1972). Superfly. United States: Warner Bros. Pictures.

Smith, C.H. (1893). Have Negroes too much liberty? Forum, XVI.

Souther, R. (n.d.). Celestial timepiece - The Joyce Carol Oates home page. Retrieved from http://www.usfca.edu/jco/.

Squires, C., & Greer, Jr., R. (1994, October 30). Frustration mounts in search. The Herald-Journal (Spartenberg S.C.). Retrieved from http://jclass.umd.edu/archive/newshoax/casestudies/crime/CrimeSmith1030a.html.

Winston, G.T. (1901). The relations of the whites to the Negroes. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, XVII.