Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

Q: I keep hearing people say that the word picnic is realted to lynchings of black people

in America. Is it ture or not?

Q: I keep hearing people say that the word picnic is realted to lynchings of black people

in America. Is it ture or not?

~ Melody D.

Detroit, Michigan

A: Over the years there have been debates on the origins of the word “picnic” and its

connection to lynching. Fact-checkers from Reuters, Politfact and other authors have

verified that the term picnic did not originate from the lynching spectacles of black

men in the United States. David Pilgrim, the founder and director of the Jim Crow

Museum, wrote an article in 2004 which stated:

“The etymology of the word picnic does not suggest racist or racial overtones. Picnic was originally a 17th Century French word, picque-nique. Its meaning was similar to today's meaning: a social gathering where each attendee brings a share of the food.”

While it is true that the word picnic did not originate from a form of lynching—“pick-a-nigger-to lynch”—numerous lynching scenes were social gatherings where people shared food, laughed, and celebrated. In fact, cursory research on the term “lynching picnic” reveals several primary sources reporting on such events.

The Bridgeport Morning News reported on December 22, 1885, reported of a broad daylight lynching of Andy Jackson, “the brutal mulat’o.” The murder of Jackson, in Montgomery, Texas, was said to be the “penalty according to the old Mosaic law, ‘An eye for an eye’” and “There has probably not been a lynching picnic in Texas in twenty years.”

The Livingston Herald reported that the lynching of George Smith,

“colored, 20 years of age,” in Omaha, Nebraska “was a picnic for people for miles

around and several hundred men from Council Bluffs took part.”

In 1879, the Fort Wayne Sentinel reported about two “Lynching Picnics,” Ben Arnold in Dakota and Marcellus Floyd “negro” in Texas.

In 1882, two “Black Brutes” who were imprisoned for the attempted murder of a telegraph operator, survived a jailbreak lynching attack. The next morning “the excitement had, to a considerable extent, died away, and all danger of a lynching picnic is considered past.” (Sedalia Weekly Bazoo)

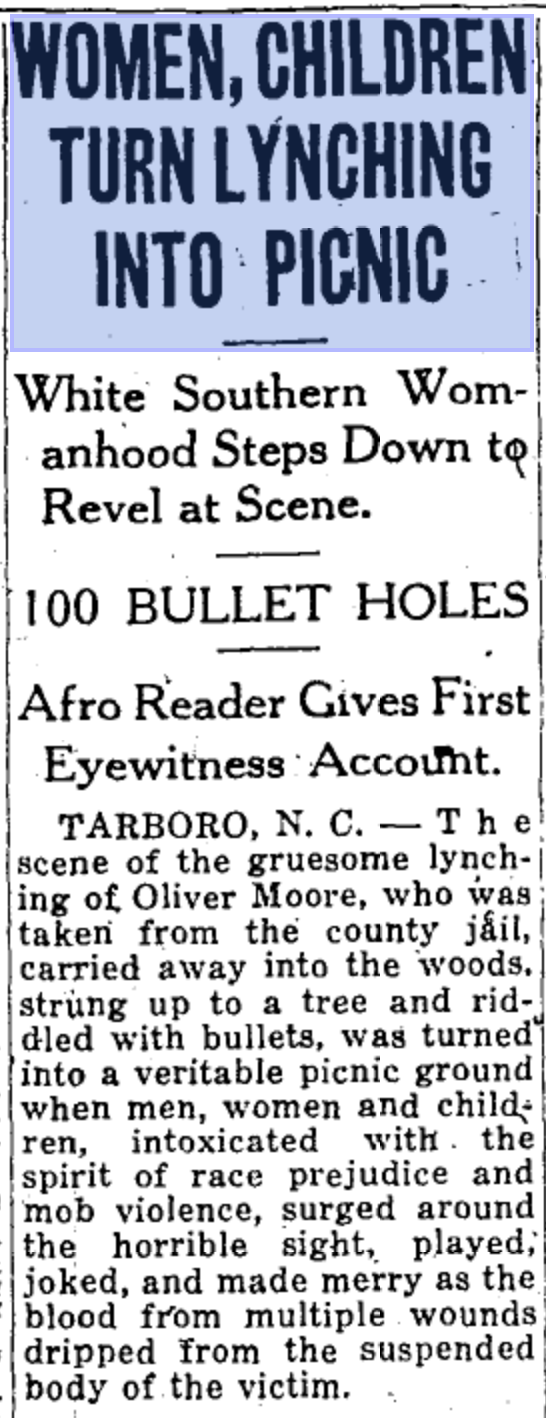

The Afro American reported a detailed brutal scene as women and children participated in the “lynching picnic” of a black man named Oliver Moore. The event “was turned into a veritable picnic ground when men, women, and children, intoxicated with the spirit of race prejudice and mob violence, surged around the horrible sight, played, joked, and made merry as the blood from multiple wounds dripped from the suspended body of the victim.” An eyewitness gave an account: “We got out and walked down the road, and we found a bunch of white men, women and children. There was no sign of terror in their faces. There was nothing but giggles and laughter as the blood dripped from the nose and from the bullet-riddled body of the victim.”

The Buffalo Times printed a story from the United Press reporting a lynching of two black men, Pete Bolen and Dit Seales, in Starkville, Mississippi. According to the article, county officials “declared a holiday, erected a double scaffold and invited all to attend. More than 5,000 men, women and children responded. The affair took on the aspect of a huge picnic. Lunches were spread on the ground and soda pop and peanut vendors were kept busy.” The event was also used by local candidates to do some “electioneering” of the white voters and the crowd all joined together to sing Isaac Watt’s hymn, “There is a land of pure delight” as the two men were hanged.

There were also little snippets of the “lynching picnic” sentiment and the commonality of them in many papers. The New York Daily Herald in 1877 reported that “Lynching picnics are now the big thing in the west” and Kansas sure was proud in their reveling of lynching picnics. The Harper Sentinel in March 1885 reported that “Kansas will have to take a back seat when it comes to lynching picnics. Nebraska takes the cake with a party wherein a man and woman both are ‘removed.’” And two months later, the Sentinel boasted of “another lynching picnic in Kansas, at Great Bend this time. You see, Independence can’t have all the fun. ‘Poor old Missouri,’” referencing a lynching that had happened in Kansas near the Missouri border. And in August of 1885, the Sentinel reported with pride how much better their lynching picnics were than the ones in Missouri stating, “Missouri comes up with a lynching picnic at Neosho, which, though not as elegantly done as we usually do such things in Kansas, was on the whole, quite effective.” In an 1891 Topeka Daily Capital article, a lynching from Hainesville, Louisiana was reported this way “Monday, a white man whipped a negro, whereupon the negro shot and killed him. Now the whites want the negro for a lynching picnic.”

There are dozens of other examples of lynching picnics in newspapers, although most victims of lynching picnics were black men not all of them were. In Iowa, two outlaws, William, and Isaac Barber, known as the Barber brothers, were lynched in 1883. The men had narrowly escaped an initial lynching picnic attempt on June 7th of 1883 from Dubuque, Iowa but were later taken from jail in Waverly, Iowa on June 8th and hanged by a mob.

A farmer named E. J. Terry from Chesterfield, North Carolina, was accused of killing his wife using rat poison. Terry’s race is not mentioned in any articles which is generally an indication that he was not a black man, nevertheless, the Xena Daily Gazette reported that if Terry is found “there will be a popular lynching picnic” as his deceased wife was well-liked by the community.

A man in San Francisco, Thomas Whitcher, also no race mentioned, was accused of molesting his daughter in 1894, and the Dubuque Herald reported that “A lynching picnic is probable.”

As the Equal Justice Institute has reported, most of the lynching’s in America after 1876 were of black men and the vast majority of so-called lynching picnics reported in the newspapers were of black men. So, there is ample evidence to conclude that many lynching picnics were associated with lynchings of black people in the United States. However, we must not conclude that the root and initial meaning of the term “picnic” was directly associated or has always been associated with the act of lynching.

Franklin Hughes

Jim Crow Museum

2021

References

A Strange Lynching. (1885, December 22) Bridgeport morning News.

https://books.google.com/books?id=KnsmAAAAIBAJ&pg=PA1&dq=%22picnic%22%2B%22lynching%22&article_id=4508%2C6051115&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjiiMShsLrxAhXQVs0KHVc3AUsQ6AEwAXoECAYQAg#v=onepage&q=%22picnic%22%20%22lynching%22&f=false

Another lynching picnic in Kansas. (1885, May 9). Harper Sentinel. Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/384898556/?terms=%22lynching+picnic%22&match=1

At Hainesville, La. (1891, April 18). The Topeka Daily Capital. Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/64719652

Broke Down Doors. (1891, October 7). Livingston Herald. Google Books. https://books.google.com/books?id=gMNlAAAAIBAJ&pg=PA5&dq=%22picnic%22%2B%22lynching%22&article_id=4374%2C1043390&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjiiMShsLrxAhXQVs0KHVc3AUsQ6AEwAHoECAoQAg#v=onepage&q=%22picnic%22%20%22lynching%22&f=false

E J Terry. (1883, March 27). The Clarion. Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/236213373/

Kansas will have to take a back seat. (1885, March 21). Harper Sentinel . Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/384895541/?terms=%22lynching+picnic%22&match=1

Legislative Service Agency. (2019, January 30). Pieces of Iowa's Past. https://www.legis.iowa.gov/docs/publications/TB/1035641.pdf

Lynching in Prospect. (1884, April 15). Dubuque Herald. Google Books. https://books.google.com/books?id=TcdCAAAAIBAJ&pg=PA2&dq=lynching%2Bpicnic&article_id=4349%2C5899290&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjN17_j-7rxAhWGF1kFHfp6AjkQ6AEwAnoECAkQAg#v=onepage&q=lynching%20picnic&f=false

Lynching Picnics in Dakota and Texas. (1879, January 19). The Fort Wayne Sentinel. Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/29211098/?terms=%22lynching+picnic%22&match=1

Lynching picnics are now the big thing in the west. (1877, August 10). New York Daily Herald . Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/329426643/?terms=%22lynching+picnic%22&match=1

Missouri comes up with a lynching picnic. (1885, August 15). Harper Sentinel. Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/385630390/?terms=%22lynching+picnic%22&match=1

Picnic Follows "Lynching Bee". (1915, August 7). The Buffalo Times . Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/441628164/?terms=%22lynching+picnic%22&match=1

Pilgrim, D. (n.d.). Blacks, picnics and Lynchings - January 2004. Blacks, Picnics and Lynchings - 2004 - Question of the Month - Jim Crow Museum - Ferris State University. https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/question/2004/january.htm

The Barbers Close Shave. (1883, June 8). 8 Jun 1883, 1 - Omaha Daily bee At Newspapers.com. Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/466627805/?terms=%22lynching+picnic%22&match=1

The Black Brutes. (1882, June 20). The Sedalia Weekly Bazoo. Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/64326067/?terms=%22lynching+picnic%22&match=1

Women, Children turn lynching into picnic. (1930, August 30). The Afro American. Google Books. https://books.google.com/books?id=n6A9AAAAIBAJ&pg=PA4&dq=%22picnic%22%2B%22lynching%22&article_id=3461%2C2129881&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjiiMShsLrxAhXQVs0KHVc3AUsQ6AEwAnoECAIQAg#v=onepage&q=%22picnic%22%20%22lynching%22&f=false