Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

Is it true that the word picnic originally came from the word pick-a-nig or pick-a-nigger? Apparently, a black person was randomly "picked" and hanged for the entertainment of whites. The whites, including families, ate from box lunches while enjoying the barbaric act. If this is true we should stop using the word picnic, replacing it with outing or gathering.

-- Sarah James, Baltimore, Maryland

Your question has several components; we will address each component. The etymology of the word picnic does not suggest racist or racial overtones. Picnic was originally a 17th Century French word, picque-nique. Its meaning was similar to today's meaning: a social gathering where each attendee brings a share of the food. The French piquer may have referred to a leisurely style of eating ("pick at your food") or it may, simply, have meant, "pick" (pic). The nique was probably a silly rhyming compound (as in English words like hoity-toity), but may have referred to an obsolete word meaning "a trifle." The literal meaning of picque-nique, which became our picnic, is "each pick a bit." A 1692 edition of Origines de la Langue Francoise de Menage mentions pique-nique. This suggests that the word had been used for some time in France. The term picnic does not appear in the English language until around 1800. 1

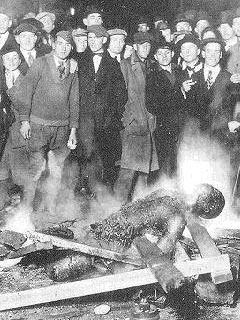

It is clear that picnic was not derived from "pick-a-nigger," "pick-a-nig," or similar racist phrases. However, some of the almost 4,000 blacks who were lynched between 1882 and 1962 were lynched in settings that are appropriately described as picnic-like. Phillip Dray, a historian, stated: "Lynching was an undeniable part of daily life, as distinctly American as baseball games and church suppers. Men brought their wives and children to the events, posed for commemorative photographs, and purchased souvenirs of the occasion as if they had been at a company picnic." 2 Bray did not exaggerate. At the end of the 19th century, Henry Smith, a mentally challenged 17-year-old black male, was accused of killing a white girl. Before a cheering crowd of hundreds, Smith was made to sit on a "parade float" drawn by four white horses. The float circled numerous times before the excited crowd tortured, then burned Smith alive. 3 After the lynching the crowd celebrated and collected body parts as souvenirs.

Often the lynch mob acted with haste, but on other occasions the lynching was a long-drawn out affair with speeches, food-eating, and, unfortunately, ritualistic and sadistic torture: victims were dragged behind cars, pierced with knives, burned with hot irons or blowtorches, had their fingers and toes cut off, had their eyes cut out, and were castrated -- all before being hanged or burned to death. One Mississippi newspaper referred to these gruesome acts as "Negro barbeques." 4

In many cases -- arguably in most cases -- lynch mobs had a particular target and confined their heinous aggression to a specific person. Blacks were lynched for a variety of accusations, ranging from murder, and rape (often not true), to trying to vote, and arguing with a white man. In 1938, a white man in Oxford, Mississippi declared that it was "about time to have another lynching. When the niggers get so they are not afraid of being lynched, it is time to put the fear in them." 5 There were many blacks lynched randomly, to send a message of white supremacy to black communities. As noted by Dominic J. Capeci, a historian, when it came to lynching, "one black man served as well as another." 6

We often think of a mob as an insane, bloodthirsty collection of adult male ruffians. However, respectable community leaders, including police, often lynched blacks. Although women and children were not typically the active aggressors they were often in the audience; and, they, too, celebrated. There were "secret lynches," but there were many done publicly -- and planned. Of course, news of an impending lynching traveled fast. Lynching was a brutal attempt to reinforce white supremacy, but it was also entertainment -- and food was present. According to Dray:

"While attendees at lynchings did not take away a plate of food, the experience of having witnessed the event was thought incomplete if one did not go home with some piece of cooked human being; and there is much anecdotal evidence of lynch crowds either consuming food and drink while taking part in the execution, or retiring en masse immediately afterward for a meal or, in the case of a notorious immolation in Pennsylvania in 1911, ice cream sundaes." 7

In 1903 a black man was lynched in Greenville, Mississippi. A white writer said, "Everything was very orderly, there was not a shot, but much laughing and hilarious excitemen... It was quite a gala occasion, and as soon as the corpse was cut down all the crowd betook themselves to the park to see a game of baseball." 8

The claim that the word picnic derived from lynching parties has existed in Black American communities for many years. Although many contemporary etymologists smugly dismiss this claim, it should be noted that there is a kernel of truth in this month's question. 9 The word picnic did not begin with the lynching of black Americans; however, the lynching of blacks often occurred in picnic-like settings.

Dr. David Pilgrim

Curator

Jim Crow Museum

January 2004

1 The information in this paragraph was drawn from several sources. Mish, Frederick C. 2003. Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary. 11th edition. Springfield: Massachusetts, p. 937. Flexner, Stuart Berg, 1983. The Random House Dictionary of the English Language. New York: Random House. p. 1465. Gove, Philip Babcock, 1993. Webster's Third New International Dictionary. Springfield, Massachusetts. p. 1711.

2 Dray, Philip. 2002. The Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America. New York: Random House. Dray's book is a well-written social history of lynching.

3 Ibid, p. 77-78.

4 Thernstrom, Stephan and Abigail Thernstrom. 1997. America In Black and White: One Nation, Indivisible. New York: Simon & Schuster.

5McMillen, Neil R. 1990. Dark Journey: Black Mississippians in the Age of Jim Crow. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, p. 98.

6 Capeci, Dominic J. 1998. The Lynching of Cleo Wright. Lexington: The University of Kentucky Press, p. 181.

7 Dray, p. 81.

8 Ibid, p. 81-82.

9 There are many reliable texts examining the lynching of blacks in the United States.

See, Ginzburg, Ralph. 1988. 100 Years of Lynching. Baltimore, Maryland: Black Classic

Press. Also, White, Walter, 1929. Rope and Faggot: A Biography of Judge Lynch. New

York: Alfred A. Knopf. And, Zangrando, Robert L. 1980. The NAACP Crusade Against Lynching,

1909-1950. Philadelphia; Temple University.