Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

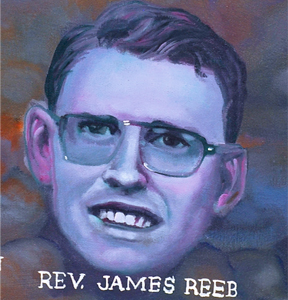

On Sunday, March 7, 1965, hundreds of civil rights marchers were violently attacked by state troopers and local police at the far end of the Edmund Pettus Bridge as they attempted to march from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital in Montgomery to advocate for voting rights for African Americans (Boyd, 2004, pp. 195-197). Like so many other individuals throughout the nation that same night, the Reverend James Reeb watched in horror as the evening news aired video coverage of the attack in Selma. Two days later, Reeb would personally fall victim to the hatred and violence of white supremacists in Selma making him a martyr on the path to justice and equality (Howlett, 1966, pp. 193-211).

In March 1965, Reeb, a Unitarian minister, resided in Boston where he worked for the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) to improve housing opportunities for low-income black residents. Reeb was a man who personified care and concern for all people from all different walks of life, and he saw in his post in Boston an opportunity to address the inequalities of society evident in the urban poverty and discrimination faced by the African American population (Mendelsohn, 1966, pp. 155-160). In his application for employment with AFSC, Reeb expressed his desire to work for racial equality:

Since my days as a Hospital Chaplain some of my deepest concerns have related to the problems of Negro people in our society. I would like to have a further opportunity to contribute to the changes that will bring them full equality in American society. But I believe the dream of justice is one of man's noblest aspirations and one which continues to grow in importance to me (Mendelsohn, 1966, p. 157).

After the tragic events of "Bloody Sunday," Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. requested that clergymen from all different denominations from around the country go to Selma to advocate for the rights of African Americans. Reeb learned of Dr. King's request during the day on Monday and wrestled with whether or not he should answer the call. A months-long AFSC investigation of lax enforcement of fire codes that Reeb believed had contributed to the deaths of four residents in a housing complex fire in late December 1964 was just reaching its height, but Reeb also felt compelled to join the protest against the brutality in Alabama that was broadcast across the nation the night before. After much deliberation, Reeb decided that he could not, in good conscience, ignore the plight of those in Selma. Instead, he would leave his wife and children at home and head to Selma on a late night flight for what was intended to be only a day trip (Mendelsohn, 1966, pp. 161-164).

Arriving in Selma in the morning on Tuesday, March 9, Reeb joined his fellow clergymen in a large crowd of protestors who were, under Dr. King's leadership, planning to make the same march to Montgomery that had been violently halted only two days earlier. Unbeknownst to the crowd, Dr. King had been working behind the scenes trying to get the legal clearance and support to execute the march but was unable to do so. Instead, the group walked to the site of the "Bloody Sunday" attack, and after a prayer service at the site, the marchers turned around and returned to the chapel in Selma from which they had set out (Mendelsohn, 1966, pp. 165-167).

Following the march, Reeb and two fellow ministers, Clark Olsen and Orloff Miller, went out to dinner at a local restaurant. The ministers, along with numerous other civil rights marchers, were referred to an African American diner called Walker's Cafe. A few steps outside of the restaurant after dinner, the three ministers saw a group of four angry white men coming across the street at them and hollering racist slurs. The ministers quickened their gait, but their attackers came up rapidly behind them. One of the attackers violently clubbed Reeb in the side of the head from behind before he could defend himself against the blow. Reeb crumpled to the ground with what was later diagnosed as a severely fractured skull and extensive brain damage. Olsen and Miller were punched, beaten to the ground, and kicked, but they were able to shield themselves somewhat from the blows to prevent severe injuries (Howlett, 1966, pp. 208-213).

After the attack, Reeb was taken to the local hospital for African Americans since it was highly probable he would be denied treatment at the all-white hospital in Selma because of his alliance with the voting rights protest. The attending physician almost immediately determined that Reeb's injuries were far worse than originally suspected. Thus, arrangements were made to transfer Reeb to the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital 100 miles away from Selma. When Reeb finally arrived in Birmingham after several delays caused by car trouble and problems obtaining police assistance for an escort, he was rushed into surgery. However, Reeb's injuries proved too severe for treatment, and he was placed on life support until his wife could make it to Alabama. In the evening on March 11, life support was removed officially bringing Reeb's life to an end (Howlett, 1966, pp. 211-223).

While Reeb lay in the hospital in Birmigham clinging to life the day after his attack, Selma residents William Hoggle, Namon O'Neal Hoggle, Elmer Cook, and R.B. Kelly were arrested on charges of assault with the intent to commit murder. After Reeb died on Thursday, officials amended the charges to murder. In April, a grand jury returned murder indictments against both Hoggle brothers and Cook but allowed Kelly to escape prosecution. At the subsequent trial in December 1965, an all-white jury acquitted all three men despite the testimony of Clark Olsen and Orloff Miller (Mendelsohn, 1966, pp. 172-173).

The attack on and death of Reeb helped draw national attention to the voting rights struggle. Although white American society had demonstrated the willingness to ignore the terrible violence perpetrated against the black population, the killing of a white minister who had traveled to the South to advocate for equality was unpalatable to a large portion of the white citizenry. In fact, Reeb's death drew the personal attention of President Lyndon B. Johnson. On March 15, President Johnson publicly advocated for the passage of a strengthened voting rights bill in a televised address to Congress. It was during this address that President Johnson famously used the popular civil rights phrase, "We shall overcome."Congress subsequently passed the Voting Rights Act, and President Johnson signed it into law in August 1965 (Anderson, 2009).

Neil Baumgartner

Staff Docent

Jim Crow Museum December 2012

References

Anderson, L. (2009, March 16). James Reeb. In Encyclopedia of Alabama online. Retrieved from http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/face/Article.jsp?id=h-2054.

Boyd, H. (2004). We shall overcome. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, Inc.

Howlett, D. (1966). No greater love: The James Reeb story. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Mendelsohn, J. (1966). The martyrs: Sixteen who gave their lives for racial justice. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

James Reeb Video