Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

Q: Does the Jim Crow Museum feel there an element of erasure since the Aunt Jemima

character has been removed from packaging and advertising?

~ J. Edward

Grand Rapids, Mi

During the Jim Crow era, many African Americans accepted roles in advertising and entertainment that promoted negative stereotypes—some well-known examples were Stepin’ Fetchit, Amos and Andy, and, of course, Nancy Green’s portrayal of Aunt Jemima. Characters like Aunt Jemima promoted damaging stereotypes. Nancy Green’s advocacy for civil rights and the poor doesn’t change the negative impact of the character she made famous.

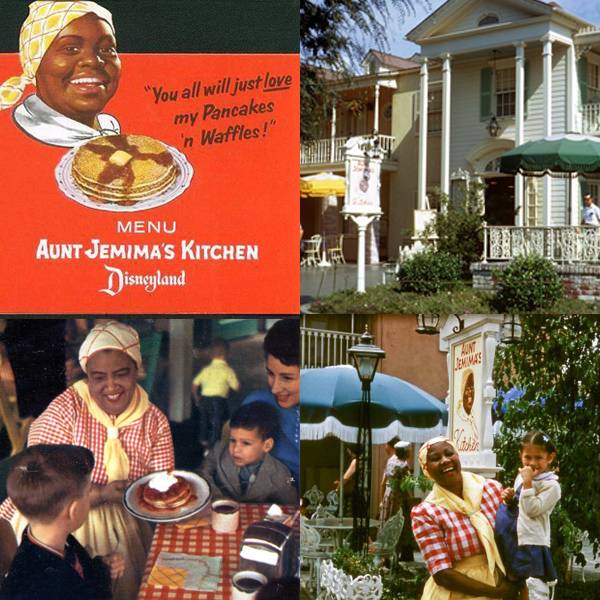

Nancy Green was not the only woman to play the role of Aunt Jemima. Many Black women played the role – at Aunt Jemima restaurants, in advertising, and Amusement Parks – for little pay and to the benefit of the companies that used them. Like Nancy Green, these women were paid to play the role of a “smiling, happy, Aunt Jemima” and to tell stories of the “good old plantation days.” There was no truth in stories of plantation bliss and Nancy Green, who was born enslaved, certainly knew that.

The Aunt Jemima character does represent an element of erased history in how the character is portrayed and what actions are included in the portrait. Over the years, David Pilgrim and the Jim Crow Museum staff discussed ways that the character could have been changed, and the products re-branded, to more accurately reflect reality. Here are three options that stand out.

First, the Quaker Oats company could have eliminated the antiquated title of “aunt” from the marketing and simply used the name “Jemima.” One of the co-creators of the brand “borrowed the Aunt Jemima name from a popular vaudeville song that he had heard performed by a team of minstrel performers” (Pilgrim, 2000). The practice of white employers addressing African Americans by “aunt” or “uncle” implied that Black people were inferior and demonstrated disrespect towards them. The term connotes a good-natured, well-mannered servant who enjoys serving white people. During the days of enslavement and throughout the Jim Crow period, most Black men would simply be called by their first name or referred to as “boy” or “uncle” by a white person. Black women were “addressed as ‘auntie’ or ‘girl.’ Under no circumstances would the title ‘Miss’ or ‘Mrs.’ be applied” (Jim Crow Etiquette). The Quaker Oats company could have shown respect to the character by simply changing the name to Jemima’s Pancakes and Syrup.

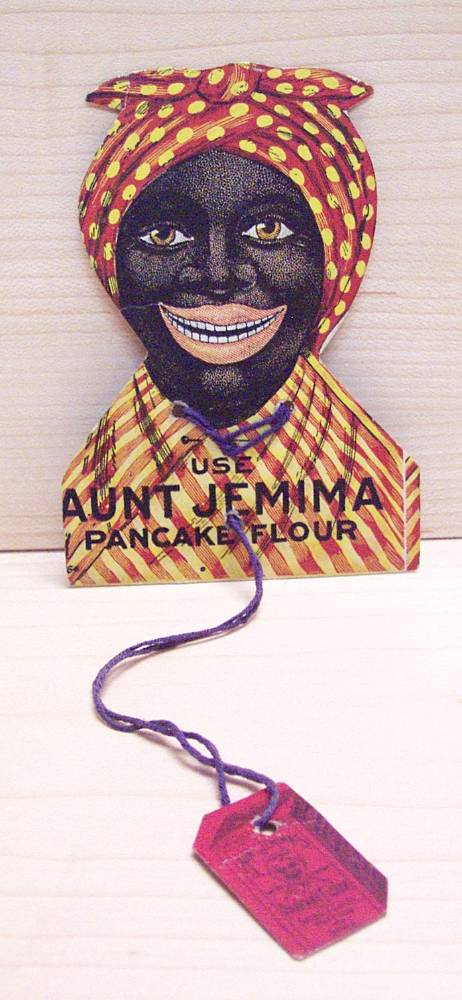

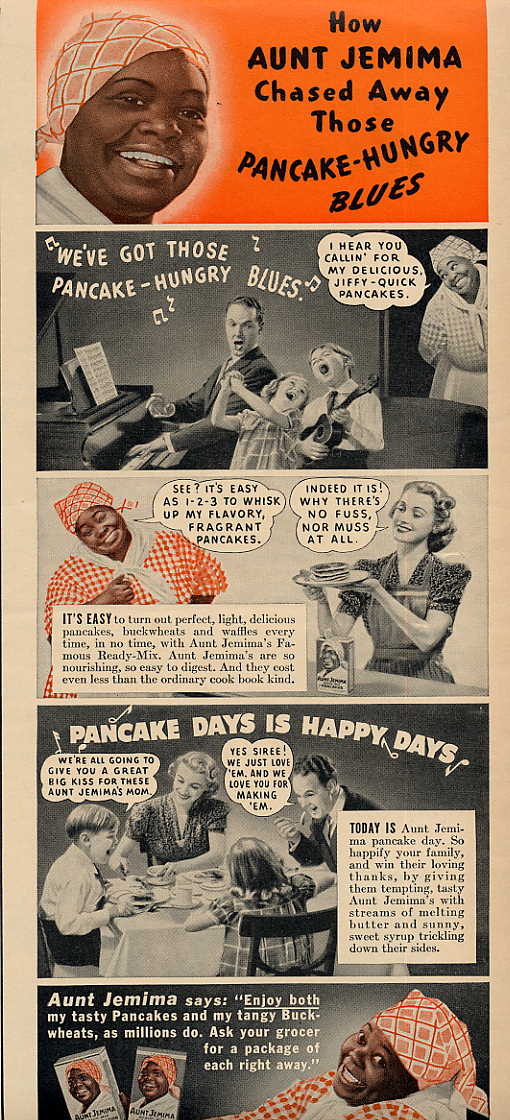

Second, the company could have removed the wide-tooth smile that accompanied many iterations of the Aunt Jemima character. In the 1940s advertisements for the Aunt Jemima variety show, the narrator opened many episodes with the phrases “Smiling, happy, Aunt Jemima” and then the character imparts some “good old plantation wisdom.” Smiling happy Aunt Jemima perpetuated the myth of the happy Black slave or servant and the benevolent white masters.

Third, the company could have shown Jemima eating with her family or eating with the

white family that she is making so happy with her cooking. Almost all of the Aunt

Jemima advertising shows her serving her “famous pancakes” to the white family, but

she is never shown eating with them. She is also never shown making food for her husband

and children. This highly constrained portrayal is, again, part of the Mammy caricature.

“She had a great love for her white ‘family,’ but often treated her own family with

disdain. Although she had children, sometimes many, she was completely desexualized.

She ‘belonged’ to the white family, though it was rarely stated. …she was a faithful

worker. She had no black friends; the white family was her entire world. Obviously,

the mammy caricature was more myth than actual portrayal” (Pilgrim, 2000). Showing

Jemima enjoying her own cooking, with her family, would have gone a long way in creating

a more positive, well-rounded character.

Third, the company could have shown Jemima eating with her family or eating with the

white family that she is making so happy with her cooking. Almost all of the Aunt

Jemima advertising shows her serving her “famous pancakes” to the white family, but

she is never shown eating with them. She is also never shown making food for her husband

and children. This highly constrained portrayal is, again, part of the Mammy caricature.

“She had a great love for her white ‘family,’ but often treated her own family with

disdain. Although she had children, sometimes many, she was completely desexualized.

She ‘belonged’ to the white family, though it was rarely stated. …she was a faithful

worker. She had no black friends; the white family was her entire world. Obviously,

the mammy caricature was more myth than actual portrayal” (Pilgrim, 2000). Showing

Jemima enjoying her own cooking, with her family, would have gone a long way in creating

a more positive, well-rounded character.

But the fact is that the Aunt Jemima shown in the branding and advertisements is a caricature, not a character, and she is fully equipped with a myriad of stereotypes associated with Black women. The Aunt Jemima brand might remind some people of happy times with their family, but it reminds many others of the indignities of enslavement and Jim Crow.

The Jim Crow Museum produced a video showing some advertisements and clips from the 1940s Aunt Jemima variety radio show. One can hear how Aunt Jemima caricatures use a broken dialect (which carries other weight as well) and is “happtifying” to serve white people. The advertising imagery throughout the years consistently shows her as a servant, with her identity completely consumed by that role. She never talks about her own children or family and she never eats what she cooks; she just serves. Older versions show her as a heavy woman with a kerchief and dressed as a servant; the newest showed her as a slimmer woman without the kerchief, but still without anything to identify her as something other than a servant. How could she, with this presentation, backstory, and broken dialect, be a positive image given what we know about the realities of enslavement and African American servitude in America’s past? The Aunt Jemima caricature is an icon of a terrible time and should have been changed a long time ago.

Jim Crow Museum staff

2022

References

Davis, R.F.L., California State University, Northridge. (n.d.). Racial Etiquette: The Racial Customs and Rules of Racial Behaviour in Jim Crow America. Nc.Gov. Retrieved February 6, 2022, from https://files.nc.gov/dncr-moh/jim%20crow%20etiquette.pdf

Jim Crow Museum. (2000, October). The Mammy Caricature - Anti-black Imagery - Jim Crow Museum. Retrieved February 6, 2022, from https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/mammies/homepage.htm

Jim Crow Museum. (2013, February 7). Aunt Jemima “I’se in town, Honey!” [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3ipamH6EEwI