Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

Q: The Green Book was such a brilliant idea. Did it offer more than just lodging, food,

and gas locations?

Q: The Green Book was such a brilliant idea. Did it offer more than just lodging, food,

and gas locations?

~ Benjamin J.

Traverse City, Michigan

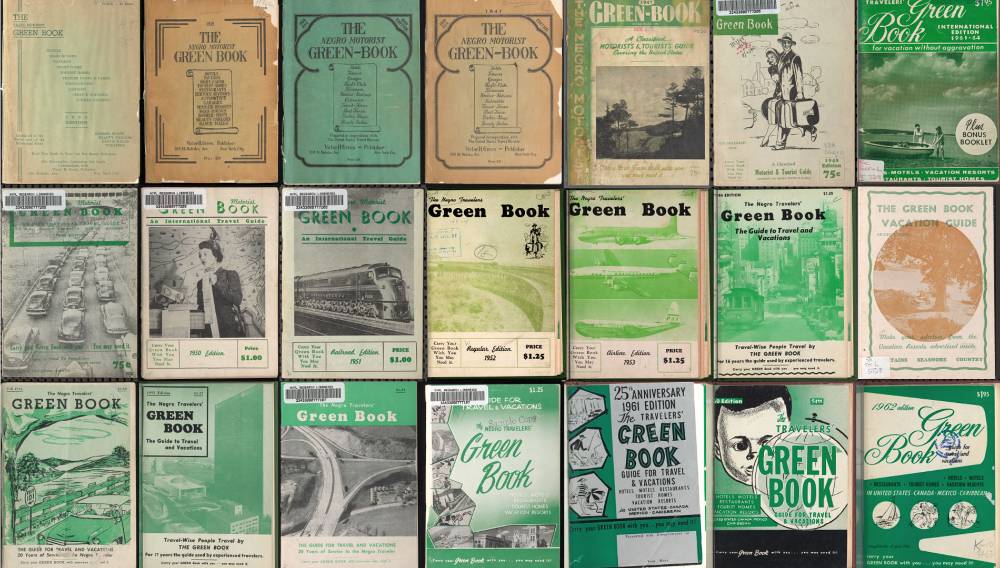

A: From 1936-1967, a guidebook called the Negro Motorist Green Book, often abbreviated to the Green Book offered a directory of safe places for Black travelers to stop. Victor Hugo Green,

a Harlem postman, began publishing this guide for African Americans which he modeled

after a similar publication for Jewish travelers. He had grown weary of the discrimination

that Black people faced when they left their neighborhoods. Rates of car ownership

exploded in the years before and after World War II, but the roadways posed many risks

for Black travelers. Green wrote in the introduction to the 1949 edition: “With the

introduction of this travel guide in 1936, it has been our idea to give the Negro

traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments

and to make his trips more enjoyable.” Initially listing roadside amenities like gas,

food, lodging, later editions also noted barber shops, beauty parlors, drug stores,

entertainment venues, parks, golf courses, shops, and other businesses open to African

Americans. The guidebook was invaluable for Jim-Crow era travelers.

The Green Book was also an indispensable resource for Black-owned businesses and aided the rising Black middle class. The books made it easier for customers to support Black businesses and complimented the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” movements that started in the 1930s. They presented individuals with the choice to support Black-owned or tolerant white-owned businesses and to push back against Jim Crow segregation, discrimination, and to avoid danger. Navigating the interstate in unfamiliar locations, Black motorists faced institutionalized racism from businesses that refused to accommodate them and encountered sundown towns that used violence to remove African Americans from city or country limits after nightfall. Outside of sundown towns were signs that warned Black people they were banned after dark. The information listed in the Green Book added convenience and dignity to travel and was lifesaving.

Green relied on his own experience and on recommendations from Black postal service union members for the inaugural guide bearing his name. The first edition was a 15-page directory specific to the New York metropolitan area, listing establishments that welcomed African Americans. Mail carriers were uniquely situated to know which private homes would accommodate travelers and mailed the listings to Green to include in his guidebook. Black travelers also assisted Green by submitting tips and recommendations. Later editions covered the entire United States, and some international cities, including information on airline and cruise trips to Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, Africa and Europe. The final edition was 99-pages.

Another publication for African Americans called Travelguide had the tagline “Vacation and Recreation Without Humiliation”, but the Green Book was the most popular guidebook. Sponsored by Standard Oil, the Green Book was available for purchase at Esso gas stations across the United States. It eventually sold upwards of 15,000 copies per year. The Green Book’s listings were organized by state and city, with the vast majority located in larger cities like Chicago and Detroit. Remote places had fewer options; Alaska had only one entry in the 1960 guide. The Green Book listed establishments in segregationist strongholds like Alabama and Mississippi, but its reach extended across the United States to any location where African Americans might face prejudice or danger because of their skin color.

With Jim Crow looming over the country, the motto on the cover doubled as a warning: “Carry your Green Book with you—You may need it.” When offering suggestions to its readers, the book adopted a pleasant and encouraging tone, avoiding discussions about racism using explicit terms. As the decades passed, the Green Book adopted a new tone and began to champion the Civil Rights movement. After Green’s death in 1960, his wife Alma continued to release the Green Book. She was not credited as an editor and publisher until 1959, but there is no doubt her contributions were significant as her husband was also working full-time as a postman. She had many opportunities to contribute, oversaw the mostly female staff, and eventually ran the entire enterprise. In 1964, the Civil Rights Act banned racial segregation in restaurants, hotels, parks and public places. A few years later, the Green Book quietly ceased publication after 30-years.

Jennifer Hasso

Jim Crow Museum

2021

Sources:

AACRN staff . (n.d.). Green book historic context AND Aacrn Listing Guidance (African American civil rights Network) (U.S. National PARK SERVICE). National Parks Service. Retrieved September 22, 2021, from https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/green-book-historic-context-and-aacrn-listing-guidance-african-american-civil-rights-network.htm

Andrews, E. (2017, February 6). The green book: The BLACK Travelers' guide to Jim Crow America. History.com. Retrieved September 22, 2021, from https://www.history.com/news/the-green-book-the-black-travelers-guide-to-jim-crow-america

Navigating The Green Book. (n.d.). Retrieved September 22, 2021, from https://publicdomain.nypl.org/greenbook-map/

New York Public Library. (n.d.). The Green Book. The green book - nypl digital collections. Retrieved September 22, 2021, from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/the-green-book#/?tab=about

Townsend, J. (2016, April 1). How the green book helped african-american tourists navigate a segregated nation. Smithsonian.com. Retrieved September 22, 2021, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/history-green-book-african-american-travelers-180958506/