Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

Q: Can you tell me more about the Double V Campaign of WWII?

Q: Can you tell me more about the Double V Campaign of WWII?

~ B. Elliott

Morgantown, VW

A: During World War II, the Pittsburgh Courier ran a weekly series called the “Double V” campaign. The campaign was an effort of the paper to bring about changes in the United States in regard to race relations. The campaign demanded that African Americans, who were risking their lives in the war, be given full citizenship rights at home.[1]

The genesis of the campaign was a letter sent to the Courier by James G. Thompson, eloquently demanding that African Americans who risk their lives fighting for the United States should be treated as first-class citizens when they returned from the battlefields.

"Being an American of dark complexion and some 26 years, these questions flash through my mind! 'Should I sacrifice my life to live half American?' 'Will things be better for the next generation in the peace to follow?' 'Would it be demanding too much to demand full citizenship rights in exchange for the sacrificing of my life?' 'Is the kind of America I know worth defending?' 'Will America be a true and pure democracy after this war?' 'Will Colored Americans suffer still the indignities that have been heaped upon them in the past?'"[2]

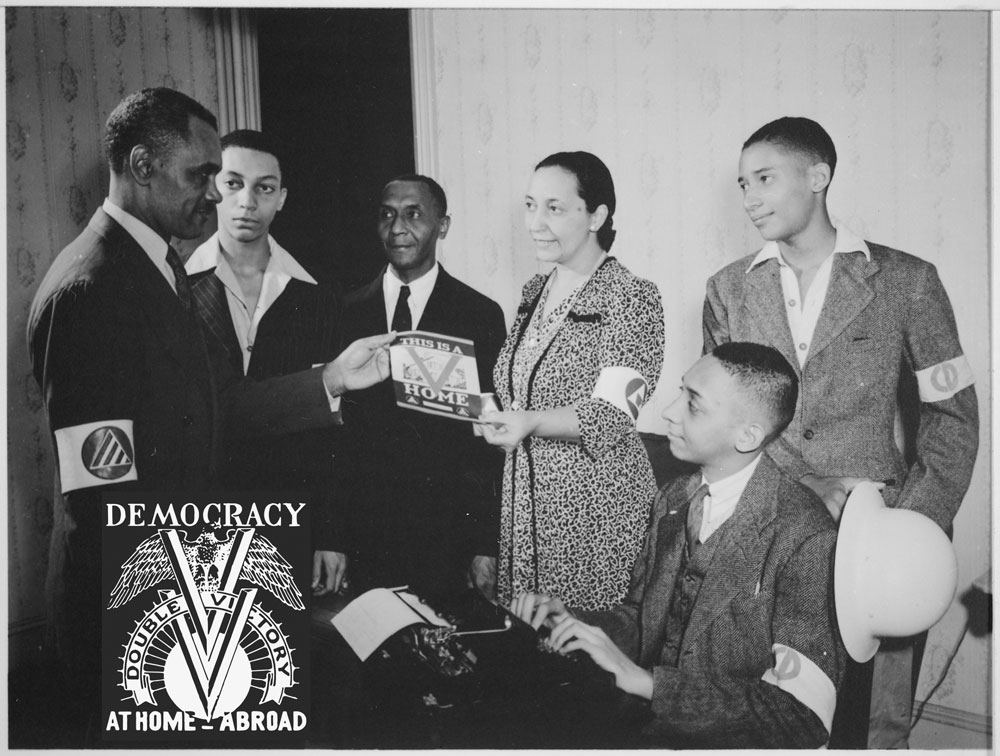

The United States and its allies had adopted a V for Victory campaign. Thompson proposed in his letter that “colored Americans adopt the double VV for a double victory.”[3] Black soldiers would fight fascism on the battlefield—and African Americans would fight racial discrimination in the United States. The Courier had fought both fights for years; therefore, it was not surprising when in the next issue (February 7), the newspaper announced a Double V campaign. Over the next several months, the Courier published articles, testimonials, photographs, and drawings supporting the campaign. They received hundreds of telegrams and letters praising the campaign, and by mid-July the paper claimed that it had recruited two hundred thousand Double V members.[4]

The campaign swept the nation—well, black communities nationwide. There were Double V dances and parades, Double V flag-raising ceremonies. Double V baseball games between black professional teams, Double V beauty contests, and a Double V song, "A Yankee Doodle Tan," introduced to a nationwide audience by NBC.[5] There was even a Double V hairstyle.

The campaign became so popular that the government began to be concerned that “such a campaign might result in a refusal of Negroes to support the war effort at the very moment when support was most needed.”[6] The Courier was accused of “hurting Negro morale” by government officials and editors of Black newspapers were summoned to Washington. Percival Prattis, the Executive editor of the Courier, responded with an editorial in the Pittsburgh Courier following the meeting:

“The hysteria of Washington officialdom over Negro morale is at once an astonishing, amusing, and shameful spectacle.

It is astonishing to find supposedly informed persons in high positions so unfamiliar with the thought and feeling of one-tenth of the population. One would imagine they had been on another planet, and yet every last one of them insists that he ‘knows the Negro.’ It is amusing to see these people so panicky over a situation which they have caused and which governmental policies maintain.

It is shameful that the only ‘remedy’ they are now able to put forward is Jim Crowism on a larger scale and the suppression of the Negro newspapers, i.e., further departure from the principles of democracy.

If the Washington gentry are eager to see Negro morale take an up turn, they have only to abolish Jim Crowism and lower the color bar in every field and phase of American life.

Squelching the Negro newspapers will not make the Negro masses love insult, discrimination, exploitation, and ostracism. It will only further depress their morale."[7]

Nevertheless, the Double V campaign increased the circulation for all Black papers, with the Courier leading the way with a circulation of over 270,000.[8] Prattis, deemed the “Negro Press” as “a force, even though catalytic, for good and improvement in race relations.”[9] Prattis recognized that the Black press could get results and elevate the status of African Americans with campaigns like the Double V campaign.

The Double V campaign lasted a year. It did not win the war against racism in the United States—that was an unrealistic goal; however, it was impactful. Black Americans embraced the war effort. The Double V campaign also bonded black people. Double V Clubs supported the war effort by selling war bonds and collecting and sending items to black soldiers. But, they also wrote letters to members of Congress to protest poll taxes, and they confronted white business leaders about their hiring practices. The campaign foreshadowed the activism that would characterize the civil rights movement.

Franklin Hughes

Jim Crow Museum

2020

Resources:

[1] PBS BlackPress: The Pittsburgh Courier. (n.d.).

Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/blackpress/news_bios/courier.html

[2] Thompson, J. G. (1942, January 31). Should I Sacrifice To Live ‘Half-American?’ The Pittsburgh Courier.

[3] ibid

[4] Washburn, P. S. (1986). The Pittsburgh Courier’s Double V Campaign in 1942. American Journalism, 3(2), 73–86. doi: 10.1080/08821127.1986.10731062

[5] ibid

[6] Simmons, C. A. (2006). The African American press: a history of news coverage during national crises, with special reference to four black newspapers, 1827-1965. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. Retreived from https://books.google.com/books?id=-2ZbYRT9bpMC&pg=PA80&lpg=PA80&dq=%22prattis%22+%22double+v+campaign%22&source=bl&ots=3NmDg4yjXA&sig=tQFg8P-LxZHfls6BVyB5cOPeaOY&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi1hoH8mOPRAhUS0IMKHR5_CKcQ6AEIJjAC#v=onepage&q=%22prattis%22%20%22double%20v%20campaign%22&f=false

[7] ibid p.82

[8] ibid p. 81

[9] P. L. Prattis, Phylon (1940-1956) Vol. 7, No. 3 (3rd Qtr., 1946), pp. 273-283