Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

Q:Tell me about William Mahone?

Q:Tell me about William Mahone?

~Roy P.

Facebook

"In 1880 a pamphlet appeared entitled John Brown and William Mahone: An Historical Parallel, Foreshadowing Civil Trouble by George W. Bagby. "In 1858 occurred the raid of John Brown," wrote Bagby, misdating

the 1859 incident at Harpers Ferry. The "raid" of Mahone and the Readjusters in 1879,

though "less bloody" was "more dangerous than that of John Brown." "Both raids occurred

in Va, and the negro was in both cases the instrument relied on to destroy the old

order of things." Comparing Mahone and Brown accomplished a number of goals. First,

memories of John Brown could easily be recalled because of the visceral fears that

his actions had engendered. It also made clear the extent of the perceived threat

to the stability of the commonwealth and called into question Mahone's loyalty to

white supremacy."

~ Kevin M. Levin “William Mahone, the Lost Cause, and Civil War History,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Vol. 113, No. 4 (2005), p. 393

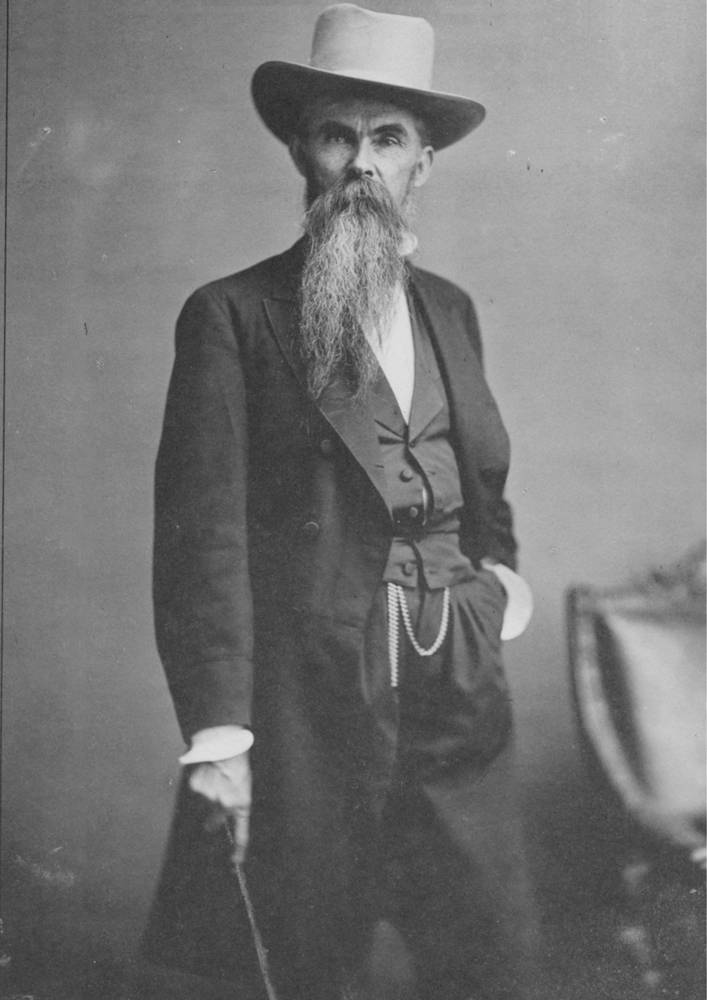

A: Recently the museum staff was asked about William Mahone, who served under Robert E. Lee. I must confess that neither Dr. Pilgrim nor I had heard of Mahone. Fortunately, I located a few recent pieces about him, including one published in the Huffington Post. The author, Jane Dailey, makes the case that General Mahone was a masterful soldier and military leader who is largely forgotten because of his actions after the Civil War.

Mahone was a civil engineer, responsible for building many roads and railroads in Virginia. Alas, he was also a slave owner—and, not surprisingly, a secessionist. He brought those beliefs into the Civil War. During the war, Mahone was a decorated Confederate General, winning many battles against the Union. Those who praise Confederate leaders, especially military officers, should celebrate General Mahone but they do not.

After the war, Mahone became a delegate from Virginia, and in 1877 became the leader of the Readjuster party, a coalition of whites and blacks, Democrats and Republicans, dedicated to “break the power of wealth and established privilege” among the white ruling class. Coming on the heels of Reconstruction efforts, the Readjusters must have seemed radical: they argued for increased funding for schools and other public facilities—and, they sought to repeal the poll tax which suppressed voting by blacks and poor whites. They also abolished the whipping post in Virginia and helped reduce property taxes for poor farmers by 20 percent. There was a brief period—in the late 1870s and early 1880s—when the Readjusters’ efforts to help blacks and poor whites produced fruit. Alas, that small progress was soon lost.

The Readjusters legitimized African Americans—and the interest of African Americas—in the political arena and the larger society. In fact, the Readjusters were changing the landscape of Virginia, for both blacks and whites:

“Black Virginians were rewarded for their votes on both the state and federal levels through political patronage. The presence of African Americans increased sharply in different agencies, including the Treasury Department, Pensions Bureau, Secretary's Office, and Interior Department. At the height of Readjuster control, African Americans made up 38 percent of workers in the Post Office. With Mahone's help, African Americans also found jobs as clerks and copyists in Washington. It was in the field of education, however, that blacks enjoyed the most visible increase in participation. Readjuster reforms increased the number of black teachers from 415 in 1879 to 1,588 in 1884, and black enrollment went from 36,000 to 91,000 during those same years. In addition, African Americans served as jurors and clerks, policemen in towns, and guards at state penitentiaries” (Levin, 2005, pg. 400).

I do not know what drove Mahone to lead these “populist” efforts, maybe he was always driven to help the underdog, or what he perceived to be marginalized people and finally recognized that he should also be an advocate for black people. In any event, he was a man who gained early fame and prestige during the Civil War, but his actions and advocacy post war for African Americans removed him as a hero to some Americans.

For more information about William Mahone see the following:

Dailey, Jane (2017) “The Confederate General Who Was Erased.” Huffington Post.

Levin, Kevin M., (2005) “William Mahone, the Lost Cause, and Civil War History,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Vol. 113, No. 4 (2005), pp. 378-412

Franklin Hughes

Jim Crow Museum

September 2017