Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

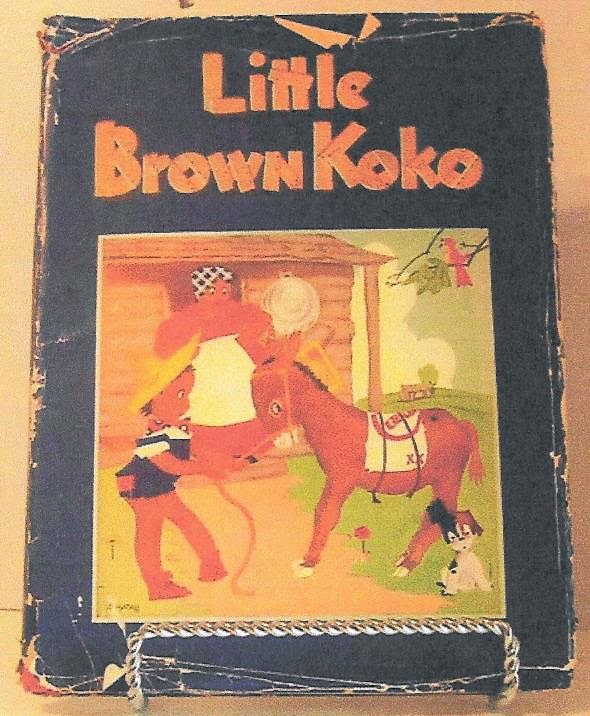

What is the harm in children's books like Little Brown Koko?

--Peter Townes

Cleveland, Ohio

Courtesy of Lynda Beck Fenwick

Some books read in the innocence of childhood raise complex issues today. Helen Bortz remembers: "There was a series of stories that appeared in issues of 'Good Housekeeping' magazine. Little Brown Koko[was] authored by Blanche Seale Hunt and illustrated by Dorothy Wagstaff..." The 'Biographical Dictionary of Kansas Artists,' compiled by Susan V. Craig, Art & Architecture Librarian at the University of Kansas, includes Dorothy Wagstaff Arens among Kansas artists active before 1945. Using the professional name of Dorothy Wagstaff, she specialized in illustrating children's books, and the image at left from "Wee Wisdom" magazine is an example of her work. She studied at Washburn College and taught at the Topeka School of Art.

She is best known, perhaps, for her illustrations for Little Brown Koko,and the image of a dust jacket cover of the book by that title appears below (above).

The online seller of the pictured book described the author, born in 1912 in Florida, as an author, teacher, and postmistress. There were six Little Brown Koko books, which together sold 600,000 copies.

Obviously this was a popular book in its time, and children who loved it, as well as parents who bought the book for their children, almost certainly did not think of themselves as racists. Nor do those who continue to remember the book from their childhoods fondly.

However, writer Stephanie Beecroft Moore, wife of a Black man and mother of two bi-racial children, points out the unintentional hurt these books and images can cause. She acknowledges that her husband does not share her degree of sensitivity to what she describes in her essay, "The Accidental Racist." While she believes "that most people are good, that they believe in equality and justice," she regards the oppression of people of color as "so deeply-embedded in our culture, it is impossible to remain uninfected." As one example of unintentional hurt, she cites finding Little Brown Koko at her children's school book sale.

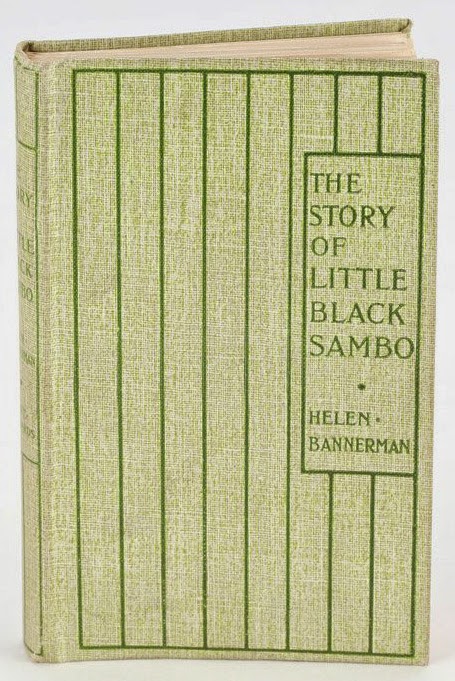

Rodney Smith remembers reading The Story of Little Black Sambo, written in 1899 by English author Helen Bannenman. I believe my own family had that children's book, as I am sure many families did. The book was a favorite well into the mid-20th century. Today many people find the book offensive, and Sambo is regarded as a racial slur.

Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan is home to the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Imagery, "using objects of intolerance to teach tolerance and promote social justice." Curator David Pilgrim has written about the fact that for many White Americans, stories like Little Brown Koko, Little Black Sambo, and Epaminondas and His Auntie are just 'cute stories.' Pilgrim writes: "I am ambivalent about removing books like Epaminondas and His Auntie from public libraries. I find the book offensive. ...However, I do not support top-down censorship. I do see the value of having racially offensive objects in the public so the objects can be used as tools to facilitate healthy, sometimes painful, dialogue."

Perhaps the issue of racism is more apparent in these books from decades ago, but if we pause to reflect on other childhood books that we remember fondly--the depictions of Native Americans, roles for young girls, the 'perfect' mother or father, and stereotypes about other nationalities as examples--we would surely find offensive depictions. Our continued affection for the books we read and loved in a different time does not necessarily reflect our attitudes today.

Lynda Beck Fenwick Link to original post

Originally published April 16, 2015