Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

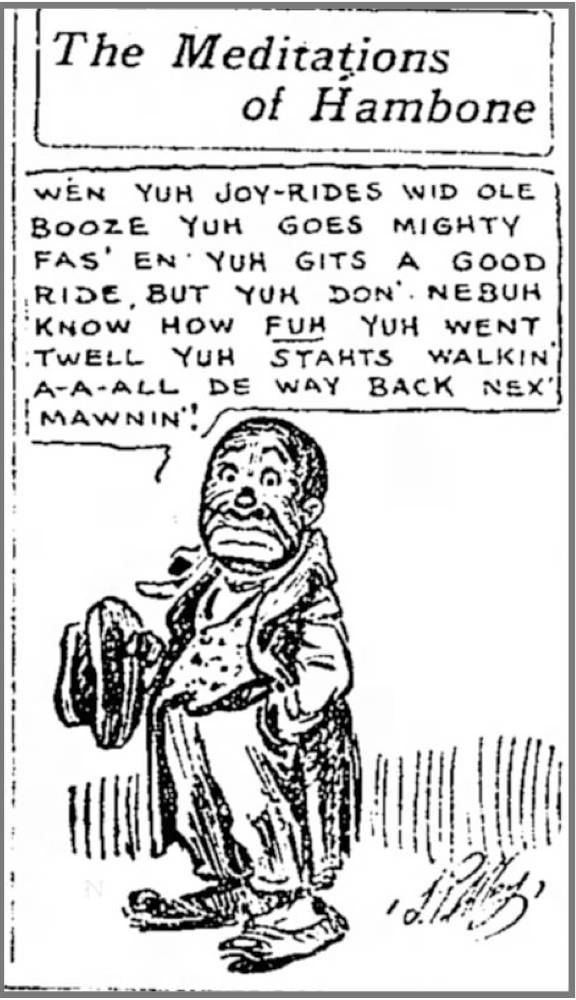

Wen yuh joy-rides wid ole booze yuh goes mighty fas' en' yuh gits a good ride. But

yuh don' nebuh know how fuh yuh wen twell yuh stahts walkin' a-a-all de way back nex'

mawnin'!

Wen yuh joy-rides wid ole booze yuh goes mighty fas' en' yuh gits a good ride. But

yuh don' nebuh know how fuh yuh wen twell yuh stahts walkin' a-a-all de way back nex'

mawnin'!I have found in my grandmother's scrapbook pages newspaper clippings of a feature called "Hambone Says" that features, in a spelling in imitation of Black southern speech, the wise sayings of a man pictured with stereotypically exaggerated facial features. She lived in Newport News, Virginia, so she would have clipped from the Daily Press or the Times Herald, but I'm wondering how wide spread this column was and whether it was limited to southern papers. I can find nothing relevant when googling the column title. Do you know anything about this--who wrote it, who published it, for how long, etc.?

Thanks for any light you can shed on this.

--Jo Anne K., Yonkers, NY

JP Alley, the creator of Hambone, was inspired by fellow cartoonist Kin Hubbard who created Abe Martin, “a home-cured philosopher” (“Kin Hubbard”). The character Abe Martin, which lived from 1904 until 1930, was the mouthpiece for Kin Hubbard to make observations about the social issues of the day (“Abe Martin History”). The comic strip was usually a one-panel image with Abe Martin giving some sort of quip or social commentary. It ran in many newspapers in the United States throughout much of the first quarter of the twentieth century.

J.P. Alley, a cartoonist, was working at Bluff City Engraving in Memphis, Tennessee, the same building as the Commercial Appeal, newspaper when he met a former enslaved man from Mississippi named Tom Hunley. Tom was cleaning offices in the building when the two men met.

“Well, upstairs, dat was where Mr. J.P. had his office—leastways his li'l room where he did his drawin' at. Twan't no regular office. I cleant up that place in dem days, an' I come trompin' up de stairs wit my mop an' bucket de fust time Mr. J.P. ever seed me. He cotch one glimpse of me, an' he jump an' holler: "Bless goodness, uncle! You stand right there 'til I can git yo' picture." Den he hole up his fingers like dis and squinch he eye at me, and fus' thing I knowed he had my picture. "Now," he says, "I got to get a name for you." And sho nuff, I'se comin' up de stairs one day a-gnawin' on a big ham-bone what a white lady had guv me. "I got it!" he hollers, "Hambone! From now on yo' name is Hambone!" An' dats what I been ever since, wit my picture in de Commercial Appeal ever' morning. Mr. J.P. he went on back to Memphis, and he dead now, but Young Mister an' his momma what was Mr. J.P.'s lady, dey draws my picture now. Hambone! Yassuh, Mr. J.P. Alley was sho one fine young white man” (“Tom Hunley”).

Some long-face folks per-nouce dey's done quit de debil, wen de truf is, de debil

wuz so fas' he jes' runned off en lef' 'em!!

Some long-face folks per-nouce dey's done quit de debil, wen de truf is, de debil

wuz so fas' he jes' runned off en lef' 'em!!Alley decided to create his own version of Abe Martin using Tom’s likeness and mannerisms. He named the fictional character Hambone. Hambone’s Meditations first appeared in the Commercial Appeal in 1916.

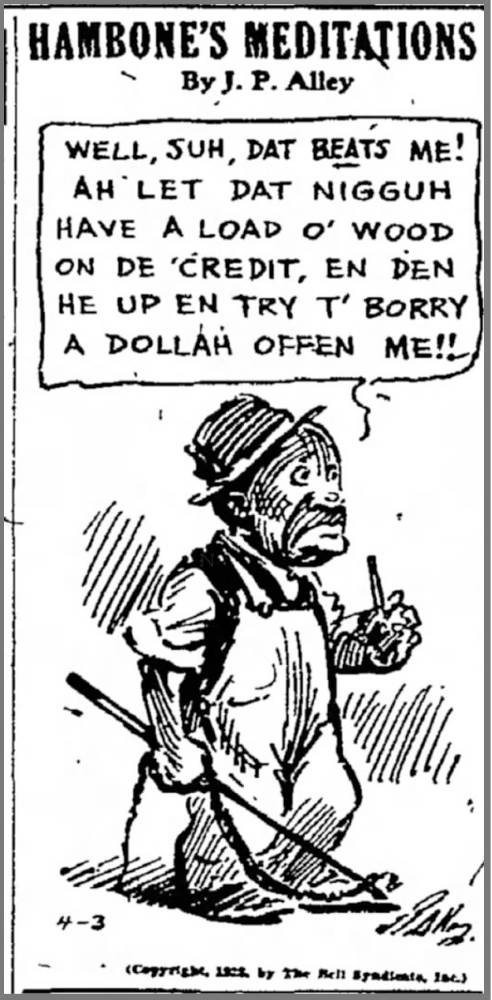

The comic strip became a success and was published in numerous papers throughout the country from 1916 until 1968. J.P.’s sons, Cal and James, did the illustrations and J.P.’s wife, Nona, wrote the panels after J.P.’s death in 1934. Usually the strip was a one panel, single scene of Hambone providing “homely common sense” about life in general. (Drew, p. 110).

In 1919, Jahl & Co. published an entire book with a collection of Hambone’s Meditations. The introduction to the collection showed how many viewed the caricatured Hambone:

“The Negro of the South lives close to the soil and retains his racial originality - his superstitions, his quaint idiosyncrasies of thought and action. Such a Negro is Hambone, chosen by Mr. J. P. Alley as the original of his delightful cartoons. He is a clearcut type of the old time darky, unspoiled by the equality ideas of the younger generation about him” (Kennedy, 1919).

Although endearing to some, the Hambone character was an example of the one-dimensional caricatures of older black men that were common during the Jim Crow period. As stated in the book, Black Stereotypes in Popular Series Fiction, 1851-1955, “Alley’s Hambone struck a chord. Everyone knew a Hambone.” Hambone came out of the tradition of the older “house servants in the southern slavery” who “passed along advice” about “good behavior” to the younger enslaved individuals. In short, Hambone was no more than the safe Tom caricature who whites could trust and who other blacks, especially males, should listen to in order to operate successfully under the “genteel white standards” of the times (Drew, pg. 108).

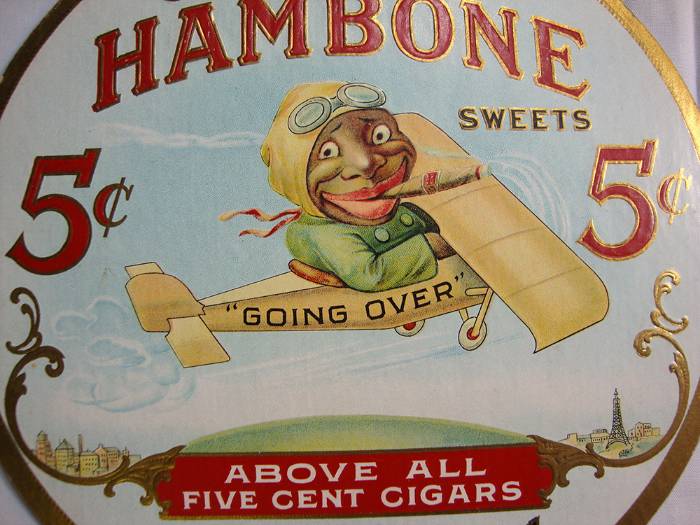

In 1929 the character Hambone was elevated from comic strip character to merchandise figure when he became the logo character for two cigar manufacturers. Hambone was usually drawn as a satirical figure in a plane, flying the 1927 Lindberg flight across the Atlantic Ocean, smoking a cigar (“Nostalgic Funk”). The Hambone image was on the cigar box and on cardboard signs used for advertising. Later, in the century, a reproduced image of Hambone appeared on a variety of items: plates, clocks, tins, cans, and glass jars (Hyman).

Hambone’s Meditations brought a nostalgic feeling to some people; this is similar to how many view Aunt Jemima today: a comforting figure of the past that brings back memories of family meals and pancakes or a figure who supplies “us with good-tempered observations of the world and its ways” (Drew, pg. 109). Many visitors to the Jim Crow Museum, particularly white visitors, say that they ‘love’ Aunt Jemima and see nothing wrong with the caricature. Most African American visitors immediately can articulate why the Aunt Jemima caricatures are offensive to them and how they differ from real life representations of the black women they know. Characters like Hambone and Aunt Jemima may be in the “image” of African Americans or “inspired” by African Americans, but the characteristics, mannerisms, dialects, and narratives of these characters are exclusively from the creator’s point of view.

Well, suh, dat beats me! Ah' let dat nigguh have a load o' wood on de 'credit, en

den he up en try t' borry a dollah offen me!!

Well, suh, dat beats me! Ah' let dat nigguh have a load o' wood on de 'credit, en

den he up en try t' borry a dollah offen me!!This is where there is a disconnect: some people believe these caricatures speak a truth about African Americans, and will not listen to African Americans and others who say, “No, they do not.” They were created from outside the African American community and they reflect the racist society’s views. Although Hambone may have been inspired by Tom Hunley, he was not Tom Hunley and he was not created by Tom Hunley; he was and remains a racist fantasy.

The Memphis Commercial Appeal won a Pulitzer Prize in 1923 for documenting “nefarious activities” of the Ku Klux Klan. The newspaper ran front-page stories accompanied by Alley’s drawings of hooded Klansmen, and was largely credited with the Klan’s defeat in the 1923 Memphis city elections (Teel, p. 109). Hambone’s Meditations and Alley’s anti-Klan illustrations were being created at the same time; this is a good example of the complex and convoluted nature of race, race relations, and local politics in the United States.

While many lamented the end of the Hambone’s Meditation panel in the newspaper in 1968 as a loss of “another old and dear friend,” African Americans knew it was time Americans stopped using their likeness as something to be ridiculed and laughed at (Drew, pg. 111). It is said that during the 1968 Memphis garbage strike protesters chanted, “Hambone just go” as African Americans were fed up with a city and a publication that viewed them as ugly, subservient caricatures (Drew pg.111).

Franklin Hughes

Diversity and Inclusion / Jim Crow Museum

December 2015

Edited 2024