Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

I recently heard that early women rights activists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony were racist against blacks. I suppose they were products of their time.

--Frank Belkin

Dallas, Texas

“The history of American feminism has been primarily a narrative about the heroic deeds of white women.” Beverly Guy-Sheftall writes in the opening of her book, Words of Fire: An Anthology of African-American Feminist Thought. In this oft-repeated narrative, “Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony are invoked, predictably, as the quintessential feminists.” Although there is plenty of evidence to suggest a different narrative, such as Guy-Sheftall’s edited volume and the many, many volumes of black, Latina, and indigenous feminists’ writing, Stanton and Anthony have been canonized as “quintessential feminists” in the popular imagination. For evidence of this, one need look no further than the Ken Burns/Paul Barnes documentary for PBS, “Not for Ourselves Alone.”

In the Burns/Barnes version of the early “women’s movement” in the U.S., race is barely mentioned and racism not at all. Instead, there is a comforting fiction that the women’s movement grew, untroubled, out of the struggle for the abolition of slavery. The historical reality departs quite dramatically from this narrative and is the subject of today’s installment of the #troublewithwhitewomen series.

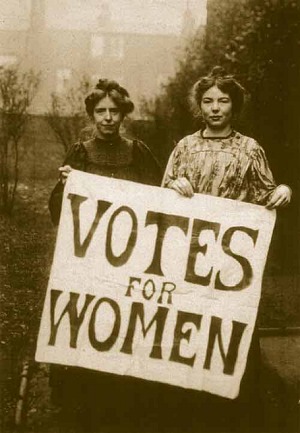

During the mid-nineteenth century there were alliances between those in the abolitionist movement and those beginning to advocate for women’s rights, sometimes called Suffragists or “Suffragettes.” Most notably, Frederick Douglass described himself as a “woman’s rights man,” largely based on the influence of Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

The abolitionist movement and the women’s movement split over the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which guaranteed the right to vote based on a citizens’ “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Despite the early support of African American men such as Douglass, suffragists like Stanton could not abide the idea that black men might get the franchise to vote ahead of white women.

Stanton didn’t hesitate to voice her opinion that white women were superior to black men, and thus more deserving of the vote. Lori Ginzberg, in her biography of Elizabeth Cady Stanton (Hill and Wang, 2009), recounts some of the racial politics here:

“Asked straight out whether she were ‘willing to have the colored man enfranchised before the woman,’ she answered ‘no; I would not trust him with all my rights; degraded, oppressed himself, he would be more despotic with the governing power than even our Saxon rulers are.’ “

“These were not merely figures of speech, thoughtless slips of the tongue and the pen. Rather, when she evoked these images, Stanton was drawing upon a powerful sense of her own class and cultural superiority.”

Yet, many feminist accounts of this history dismiss and distance racism from the core values of feminism or feminist leaders. For instance, Nancy F. Cott, in The Grounding of Modern Feminism (Yale University Press, 1987), locates this racism outside the movement for women’s rights and shifts it to ‘the surrounding society,’ as in this passage:

“Despite links between early woman’s rights and anti-slavery reformers, the suffrage movement since the late nineteenth century had caved in to the racism of the surrounding society, sacrificing democratic principle and the dignity of black people if it seemed advantageous to white women’s obtaining the vote.”

Here, Cott paints the women of the suffrage movement as passive victims who “caved in to” the racism “of the surrounding society,” rather than the active, political agents they, in fact, were.

Stanton was no passive victim “caving in to” racism of the society around her. Returning to Ginzberg (Elizabeth Cady Stanton, 2009), the political landscape of the late nineteenth century was one in which fault lines of race and gender were especially sharp, and Stanton played an active role in sustaining them and using them to her political advantage. In this passage, Ginzberg recounts some of the ways Stanton’s racism was an effective mobilizing tool for the women’s movement:

“Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s positions on the relative worthiness of black men and white women as citizens …. her choice of all-too-familiar racist language had broad and lasting consequences, both theoretical and strategic, for the movement she helped lead. By claiming that some American citizens were more worthy of rights than others, Stanton helped lay the groundwork for a defense of woman’s rights based on race, respectability, religion and class that would be hard to shake. Surely Stanton and Anthony understood this when they reported on the formation of a ‘White Woman’s Suffrage Association’ in Washington, D.C., or admitted that the proposed Fifteenth Amendment ‘rouses woman’s prejudices against the negro’ while increasing ‘his contempt and hostility toward her as an equal.’ Furthermore, this appeal to prejudice, whether it was an intentional strategy or not, worked. One woman wrote Stanton and Anthony’s newspaper, The Revolution, to declare that she had ‘never thought, or cared, about voting till the negroes began to vote,’ but now ‘felt my self-respect rise.’ She went on: ‘If educated women are not as fit to decide who shall be the rulers of this country, as ‘field hands,’ then where’s the use of culture, or any brain at all? One might as well have been ‘born on the plantation.’”

“Elizabeth Cady Stanton had been arguing for years that it was women’s lack of self-respect that caused them to defer their demands….[now] white women’s self-respect, as this letter writer suggested, could be heightened by comparison with people of ‘lesser’ races. Pleased by evidence that women were developing their self-esteem and so would demand their rights, Stanton seems not to have worried that advocating woman’s rights on this basis, and severing the movement’s ties to its abolitionist and antiracist roots, might damage the cause’s claims to universal justice. Nor did she express any concern that her use of racist language to denigrate black men, along with her implicit embrace of a politics of white racial pride, might diminish the movement’s appeal to African American women themselves. Whether or not she meant to endorse an explicitly racist tactic to draw new groups of white women into the cause is impossible to know; that she published the letter, entitling it, ‘A Washington Convert,’ suggests that she was willing to take the risk.”

I’m struck here by the affective, that is the way emotion plays into the political strategy. Stanton had identified white women’s “lack of self-respect” (today, we’d say “self-esteem”) as a barrier to her efforts at organizing. The woman writing in to their newspaper confirms this, saying “I never had an interest in voting.” What sparks the sudden boost in this woman’s “self-respect”? The prospect of that “the negroes began to vote” and then she “felt my self-respect rise.”

There is additional evidence that the racism of the early women’s movement was central rather than peripheral to the movement. In Barbara Andolsen, in her book about racism and the woman suffrage movement, “Daughters of Jefferson, daughters of bootblacks”: racism and American feminism (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1986), she observes:

“… the white women who led this movement came to trade upon their privilege as the daughters (sisters, wives, and mothers) of powerful white men in order to gain for themselves some share of the political power those men possessed. They did not adequately identify ways in which that political power would not be accessible to poor women, immigrant women, and black women.” Yet despite the blatant racism and class bias of the women’s suffrage movement, black women, discouraged and betrayed, continued to work for their right to vote, both as blacks and as women, through their own suffrage organizations.”

The Guy-Sheftall anthology Words of Fire, mentioned at the top of this piece, offers an account of continuous feminist intellectual tradition in nonfictional prose of African American women going back to the early nineteenth century when abolition and suffrage were urgent political issues. Works like this one provide a useful correction to the familiar narrative of American feminism, but this history is largely unknown to most white feminists today. More than simply the absence of knowledge about black feminist intellectual tradition in the U.S., there is a real lack of awareness about the role of whiteness in shaping early feminism.

An important corrective to this lack of awareness is Louise Newman’s excellent book, White Women’s Rights: The Racial Origins of Feminism in the U.S. (Oxford University Press, 1999). Newman makes a convincing case that enveloped an explicit racial ideology to promote their cause, defending patriarchy for “primitives” while calling for its elimination among the “civilized.” She writes:

“Feminism developed in conjunction with—and constituted a response to—the United States’ extension of its authority over so-called “primitive” peoples, and feminism was part and parcel of the nation’s attempt to assimilate those peoples whom white elites designated as their racial inferiors.” (p.181)

Newman’s argument is that in the time period from 1848 to 1920, the “white woman movement” – as she rightly refers to it – affirmed (white) women’s racial similarity to (white) men while at the same time asserting (white) women’s sexual difference from (white) men because they believed sexual differences formed the bedrock of whites’ civilization. This “functional ambiguity,” (as Nancy F. Cott describes it) was not so ambiguous at the time. Social evolutionary theories of the time specified quite plainly that white women were both fundamentally similar to white men (because of “race”) and fundamentally different from white men (because of “sex”).

These evolutionist theories that white women were both the same as and different than white men opened up new social and political roles for white women as “civilizers” of the race, strengthening longstanding beliefs in (white) women’s moral superiority. Moreover, the effort to establish the United States as an empire, and the extension of missions, both domestically and abroad, fundamentally influenced the direction and content of white feminist thought in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The reality is that white supremacy and feminism were completely intertwined at the root. This is not simply an old problem of a previous century, or of individual white women who “caved in to” the racism of the surrounding society. Rather, white supremacy is baked into white feminism. White feminism – if it’s only focused on a kind of crude parity with (white) men – is not incompatible racism. In fact, many of the avowed white supremacist women I studied in my study of Cyber Racism view themselves as feminists. And, there’s nothing inconsistent between white supremacy and white feminism. That’s why it’s so important for a critically engaged feminism include a commitment to racial justice.

The white feminist thought shaped by evolutionist theories, imperialism, and missionary zeal continue to shape the feminist movement today. You can see this in any number of examples, such as the critique of Eve Ensler’s brand of white feminism I mentioned last week, in the corporate feminism we’re presented with today, and in popular culture portrayals of white women.

I’ll have more to say about all this in another installment of the #troublewithwhitewomen series.

Jessie Daniels

Racism Review

Originally published February 18, 2014

Racism Review