Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

One of the museum staff mentioned a "Battle Royal" where black boys would be paid to fight one another blindfolded at carnivals, can you provide more information about these battles??

--D. Manning, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

It was announced in the newspapers as an "Athletic Show" and it began with a "battle royal" boxing bout among five Negroes. Five burly men, stripped to the waist, entered a roped arena on a platform. At the stroke of the bell two couples immediately began sparring. The fifth man then pitched into one of the boxers who seemed to be having the best of it, thus breaking up the pair. The released man turned to the other group and picking out one of the men began without warning to punch him. And so the fight proceeded. No matter how cleverly a man might be holding his own he was always in danger of having someone come at him from behind with a none too well padded fist. Scientific boxing was not in evidence. The contest was one of brutal physical endurance. When a man could keep it up no longer he left the ring and the winner was the man who stayed in longest. As announced, the winner was to receive $4.00, the second place man $2.00, and the third $1.00.

(Recreation in Springfield, Illinois 1914)

This scene was commonplace at many carnivals, fairs, and boxing matches throughout the American landscape. Blindfolded African American men and boys beat each other senseless for the comedic pleasure of the audience and in the hopes of winning a few dollars. These battle royal matches were held at many types of venues and involved anywhere from four to thirty blindfolded "negroes." While there were a few instances of white participants, the overwhelming majority of fighters were African American males. Advertisements for these events typically promoted them as comic events with "Negro" or "Colored" combatants.

At fairs, carnivals, benefits, and holiday festivals throughout the country, battle royals were among the featured events.

I have to ask, who leaves these festivities with pride and feeling good about themselves? How do the men and boys who took part in these battle royals view not only their own self-worth, but the value of any person of color?

During slavery, a battle royal or Free-for-all battle, was a common activity. In the book Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves, Kentucky Narratives, J.R. Wilkerson recounts some of the recreational activities of the enslaved, as described by un Force and Elvira Lewis:

"Another kind of contest was called "A free for all". Here a ring was drawn on the ground which ranged from about 15 ft. to 30 ft. in diameter depending on the number of contestants who engaged in the combat. Each participant was given a kind of bag that was stuffed with cotton and rags into a very compact mass. When so stuffed, the bags would weigh on an average of 10 pounds, and was used by the contestants in striking their antagonist. Each combatant picked whichever opponent he desired and attempted to subdue him by pounding him over the head with the bag, which he used as his weapon of defense. And which was used as an offending weapon. The contest was continued in this manner till every combatant was counted out, and a hero of the contest proclaimed. Some times two contestants were adjudged heroes, and it was necessary to run a contest between the two combatants before a final hero could be proclaimed. Then the two antagonist would stage a battle royal and would continue in the conflict till one was proclaimed victorious. Sometimes these Free-For-All battles were carried on with a kind of improvised boxing gloves, and the contests were carried on in the same manner as previously described. Very often, as many as 30 darkies of the most husky type were engaged in these battles, and the contests were generally attended by large audiences. Being staged during the period of favorable weather, and mostly on Saturday afternoon; these physical exhibitions were the scenes of much controversial conflict, gambling, excessive inebriation and hilarity" (Slave Narratives, J.R. Wilkerson: Tinie Force and Elvira Lewis, 2006).

Even the United States Military enjoyed a good "negro battle royal" and in many cases, the participants were enlisted men.

"The battle royal between five colored heavyweights proved one of the biggest things yet and the crowd went wild at the efforts of the contestants to knock out anybody that happened along. Two men went down and out in short shift narrowing the contest down to three men. These furnished no end of hilarity until there was no one left but a big husky soldier, who strutted from the ring the winner of a $15 purse" (May 27, 1904).

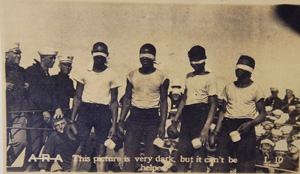

The Washington Herald published a story called "Negro Troopers Enjoy Battle-Royal" in 1918. The story, accompanied with a picture, went as follows;

"It's a great old game, the battle-royal. It used to be that boxing promoters would get a bunch of husky black boys to climb into a ring and battle for a ten-dollar note, the note going to the boy who was on his feet last. They've made it a little different with some of our negro troops overseas. At a recent athletic carnival in England a bunch of troopers were blindfolded and sent in a ring with the above amusing result" (December 9, 1918).

Battle Royals were primarily a part of boxing bouts and wrestling matches as undercards

and in some cases, fighters used the opportunity to establish a boxing career. However,

most often the negro battle royal was a comedic mockery and provided the participants

with little more than the opportunity to be laughed at and ridiculed.

Battle Royals were primarily a part of boxing bouts and wrestling matches as undercards

and in some cases, fighters used the opportunity to establish a boxing career. However,

most often the negro battle royal was a comedic mockery and provided the participants

with little more than the opportunity to be laughed at and ridiculed.

"Six big, husky negroes were mingling in a battle royal at the old Long Acre Club, in Twenty-ninth Street, one night. To be more exact, five were big, but the other hadn't flirted with a steak in weeks. It so happened that the five picked on the one, and ere long the little fellow was knocked down. He was wise, this little fellow, and, rising on all-fours, he crawled across the ring, climbed over the lower rope, and dropped to the floor. 'Hey, you!' yelled Mike Newman, 'ain't you going to fight any more?' 'Oh, yes 'Marse Newman. Ahm goin' to fight plenty more. But no more to-night!' replied the coon, and he kept his word" (The New York Tribune, August 18, 1915).

Maybe one of the most detailed descriptions of a battle royal came in this 1920 Richmond Times recap of a boxing card.

"Closing the bill was the battle royal between six colored fighters. This was the funniest bout that has been staged in this city for some time. Every one crowded to the ringside to see the grand hubbub. They entered the ring, all kinds, big and husky, black and tan. With no referee in the ring they went at it. One darky opened up with corking another boy and they all went after him. He was sent rolling out of the ring for his offence. Down they went one after another until only three were left. Two of these set out to beat the other one up. Reading defeat, he retired and left one tall lanky "brown skin" and another husky black boy to settle the argument. They fought for about a minute when the black one was sent sprawling through the ropes and the lanky "high yella" grinned and picked up the money the fans had thrown in the ring and was declared the victor" (October 29, 1920).

Some battle royal fighters were able to use their success as a springboard to a professional boxing career. Legends like Jack Johnson, Joe Gans, and Beau Jack all started in a negro battle royal.

Jack Johnson Heavyweight Champion (1908-1915):

"Taking part in one of the most humiliating creations of the Jim Crow era, the Battle Royal. A backroom spectacle in which six or eight or ten black boys often blindfolded, were set to punching one another while drunken white men jeered them on. The last one standing got the prize, usually, a fist full of tossed coins. Jack Johnson was often the last one standing." (PBS film; Unforgivable Blackness: Rise and fall of Jack Johnson)

"I went down to Springfield, Ill., about seven years ago to referee a series of glove contests, and the management, for a humorous opener, staged a battle royal in which six colored men, among them Johnson, took part. Jack was the last to enter the ring, and directly he did he landed one of his every-man-for-himself opponents a wallop on the jaw, dropping him as if shot. Two big blacks then sailed in after Johnson, who danced out of distance, and, before his opponents knew what had happened, they were on the floor, because they foolishly permitted their respective jaws to come in contact with Jack's right mitt. The other blacks thought of the old adage of: "He who fights and runs away will live to fight another day" and crawled out of the ring." (Inside facts on Pugilism)

Joe Gans Lightweight Champion (1902-1908):

"Although first money amounted to but $5, almost every negro with fistic ambition in Baltimore entered. These battles made a big hit. One night Joe Gans, then working in the fish market, made an application to enter the contest. He was asked whether he had had any experience and frankly admitted that the sport was all Greek to him. 'But you know what these battle royals are don't you?' he asked, 'you've got to fight and mix it up all the time, and if you quit you don't get anything-see?' Joe went on and was very successful." (August 12, 1910).

Beau Jack lightweight champion (1942,1944):

"During the 1930's, wealthy white men in the South amused themselves by placing a group of perhaps 6 to 10 young men, usually blacks, blindfolded inside a ring for a battle royal. The youngsters would slug away until only one was standing, and then the coins would shower down. After Beau Jack, who had shined shoes at the Augusta National Golf Club, showed his prowess in one such battle, club members -- including the renowned golfer Bobby Jones -- bankrolled his entry into pro boxing" (February 12, 2000).

Although in some cases, a battle royal was a chance for a person of color to get noticed in the world of boxing, the contests were demeaning and exploitative. Like many debasing practices toward black Americans, Battle Royals did not begin in the United States, and were not necessarily initially intended to degrade peoples of color. For an early history of battle royal see SB Nation, Wrestling with the Past: The Bizarre Origins of the Battle Royal:Part One and Wrestling with the Past: The Bizarre Origins of the Battle Royal: Part Two. For rare footage of a so-called "negro Battle Royal, see Boxing Hall Of Fame footage.

Reading the first portion of the Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison allows one to truly feel the disgraceful impact a "negro" or "colored" battle royal could have on individuals. Ellison captured the essential truth that, regardless of what a person of color could offer society, his or her opinions did not matter, they were entertainment; they were labor, and very little else. The Godfather of Soul, James Brown spoke of his experience as a boy in a battle royal:

"Because of my reputation the other kids always pointed me out to the white men who came around to recruit scrappy black boys to be in the battle royals they put on at Bell Auditorium. In a battle royal they blindfold you, tie one hand behind your back, put a boxing glove on your free hand, and shove you into a ring with other kids in the same condition. You swing at anything that moves, and whoever's left standing at the end is the winner. It sounds brutal, but a battle royal is really comedy. I'd be out there stumbling around, swinging wild, and hearing the people laughing. I didn't know I was being exploited; all I knew was that I was getting paid a dollar and having fun. A lot of good boxers started out in those things. I think Beau himself, when he was a kid, was in battle royals at the Augusta National Country Club. I was too classy for battle royals, though, because I could really box" (James Brown: The Godfather of Soul, an Autobiography, 1986)

There are many aspects the museum staff encourage visitors to consider when talking about the Battle Royal or African Dodger. What is the emotional and psychological impact of participating in such events? The participant becomes the target of ridicule and mockery in order to provide entertainment for a group that calls itself superior. How do participants view themselves? How do they view similar others, their family, their friends? How are the effects of Jim Crow perpetuated in attitudes about self and others that are still visible today? If our society is going to move past its racist history we must have a national conversation about topics like the negro battle royal and the continuing impact on US culture.

Franklin Hughes

Diversity & Inclusion/ Jim Crow Museum

2014