Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

What was your opinion of Julia, the television show?

--Thomas Johnson, Spokane, Washington

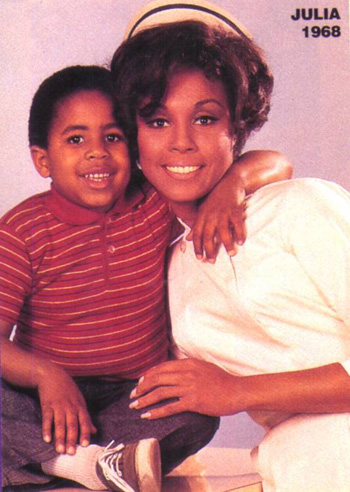

Julia was a light-hearted NBC sitcom that ran for 86 episodes from September 17, 1968 to March 23, 1971. The show is often hailed-and rightly so-as one of the earliest attempts to depict an African American woman in a non-stereotypical way. The show starred Diahann Carroll, an actress who had starred in the films Carmen Jones and Porgy and Bess in the 1950s. In 1962, she won a Tony Award for her performance in No Strings.

Julia was a widowed single mother-her husband died as a fighter pilot during the Vietnam War-who worked as a nurse in a doctor's office. Her son, Corey, was approximately six to nine years old during the show's airings. He barely knew his father before his father died.

Julia and Corey lived in an almost exclusively white world. The doctor was white. The coworkers were white. With the exception of two dating pursuers, most of Julia's friends were white. Corey's friends were white. The neighbors in the apartment building where they lived in Los Angeles were white. It was a fictional world where race, race relations, and racism did not matter much. The producers of Julia tried to create a show where the relatively few black characters (and the many white characters) were not defined by their race, but issues related to race sometimes peeked through the curtain. This happened in the episode Dancer in the Dark, where the discussion of interracial dating arose. The black person in question opposed it. That episode also dealt with Uncle Tom-ism, black militancy, and what would later be referred to as affirmative action, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DeO44a7wp38. This episode is a not-so-subtle put down of black militancy.

Almost from its inception, the show was criticized for being apolitical and unrealistic. Carroll was criticized for playing a role that denied her blackness. Gil Scott Heron, the jazz poet, implied that Julia, was a cartoon. Robert Lewis Shayon, a writer for the Saturday Review, wrote that Julia's life was "a far, far cry from the bitter realities of Negro life in the urban ghetto, the pit of America's explosion potential." He might have also added that Julia sometimes employed a housekeeper, see www.youtube.com/watch?v=mIzqjp0iPmE.

It was the 1970s and demonstrations (violent and non-violent) were relatively commonplace-as were the conditions that make people protest. Julia was seen by Heron, Shayon, and others as a wasted opportunity to make a different, more political, statement. But, the show was often (though not always) apolitical, especially when the topic was race relations. Even Carroll who often defended the show as a "fantasy," said, "I'm a black woman with a white image. I'm as close as they can get to have the best of both worlds. The audience can accept me for the same reason: I don't scare them."

As a child, I loved Julia, the show and the character. Even as a pre-teenager, I was aware that Julia's character was different from Beulah, a black maid in a 1950s show of the same name, Rochester, the manservant in The Jack Benny Show, and the entire cast of Amos 'n Andy. These were characters as caricatures, one-dimensional mammies, toms, and coons. Julia was smart. She did not say dis and dat. She did not kowtow to whites. She was a fully developed character, on equal footing with the other members of the cast. She was a Mary Tyler Moore character-or maybe I should say Mary Tyler Moore was a Julia character; either way: a smart, independent professional woman.

Today, I still appreciate the show and what it accomplished: offering the nation a different view of black lives-and paving the way for other sitcoms focused on African Americans, such as the highly successful The Cosby Show and the critically acclaimed Frank's Place. I understand the criticism that the show was often apolitical regarding race relations. And, I understand that when the representations of a group (in this case 1970s African Americans) are scarce, the few representations (in this case Julia) will be pressured to address important concerns of the group. That is, of course, unfair to the show. Besides, should we really trust the handling of racism or poverty in any situational comedy? It is, after all, a comedy.

I must confess that there is one criticism of the show that resonates with me, namely, the absence of a father. Why couldn't a successful black woman have a life partner? Were the show's writers afraid that the American audience, composed mainly of white people, would be put off by (even) sanitized inferences of sensuality between a black husband and wife? I believe so.

Dr. David Pilgrim

Curator / Jim Crow Museum

2014