Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

There is so much emphasis this time of the year (February) on the contributions of well-known African American women. Why don't you share some info on an African American woman, preferably someone we haven't all heard about.

--Tawanda Jenkins - Lansing, Michigan

Even after the integration of minor- and major-league baseball in the mid-1940s, the Negro Leagues continued for another decade and a half. The top black players were now in Organized Baseball, but others filled the rosters of all-black teams. One was a Minnesota native, Marcenia Lyle Stone, better known as Toni Stone.

In 1953, Stone became the first woman to play in the Negro American League. She had already been playing with men and boys for years, going back to the sandlots of St. Paul where she grew up.

It's not uncommon for conflicting information to surround Negro League players. The recordkeeping in the Negro Leagues wasn't as formal or as organized as it was for the white major leagues. With Toni Stone, however, the misinformation was in part by design as the league, in attempting to enhance her status as a drawing card, shaved years off her age and added thousands to the salary she was actually being paid.

Even the details of her younger years aren't clear. In Women in Baseball: The Forgotten History, Gai Ingham Berlage writes, "Unlike many other women ball players, she [Stone] hadn't first played softball and then switched to baseball." However, many sources, including Terri Ann Finneman, in an anthology, The Brotherhood of Baseball: Black Baseball in Minnesota, 1880-2000 by Steve Hoffbeck, maintain Stone had played for the Girls Highlex Softball Club in St. Paul.

What is clear is that Stone was born in 1921 and by 1937 was playing on the Twin Cities Colored Giants semipro team. Jimmy Lee, writing about the Colored Giants in the July 30, 1937 Minneapolis Spokesman, said, "The team has the distinction of having a girl pitcher on its roster. No other team in the Northwest can boast the same. Miss Marcenia Stone, 16-year-old girl athlete, has been doing much to amuse the fans with her great catcher [sic] and wonder hitting power."

In 1936 and for the first half of the 1937 season, the manager of the St. Paul Saints of the American Association was Gabby Street, who had been a catcher in the major leagues and had managed the St. Louis Cardinals earlier in the 1930s. Through her persistence, Stone reportedly got Street to agree to let her work out at a baseball school he operated. In a July 1953 Ebony article, Stone quoted Street as saying, "I haven't anything to do with the color line that keeps your people out of baseball. And I haven't got anything with that other unwritten law that keeps women out of the game. But if I did-"

(It is possible this quote, and perhaps the entire story of her encounter with Street, was fabricated; it is in the same article with another quote by Stone about being offered $12,000 to play in the Negro Leagues, a figure she later revealed as being vastly inflated.)

Finneman says that little is known about Stone's life from 1937 until 1946, when she moved to California, drawn by a sick sister. (The 1953 Ebony story says she moved west with her family, but the story of the ailing sister is backed up by a 1991 interview Stone did with Ron Thomas of the San Francisco Chronicle.) In San Francisco, she got to know Allroyd Love, who managed the Wall Post American Legion team. Stone began playing for Love's team and then joined a barnstorming semipro team, the San Francisco Sea Lions.

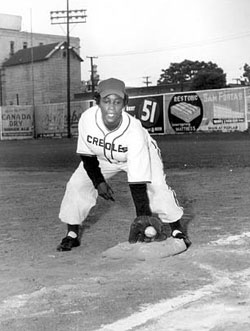

In 1949, she began playing with the New Orleans Creoles, described as a "very good semipro team" by Negro Leagues historian Larry Lester. Stone was married by this time to a man who wasn't keen on her baseball career. Yet during the spring and summer she traveled the country playing baseball before returning home to Oakland in the offseason. In 1953, Stone signed to play with the Indianapolis Clowns in the Negro American League.

Stone was the first woman in the organized Negro Leagues and, as such, drew a great deal of attention. Some had to do with her baseball skills, but much of it focused on her feminine side. A set of pictures-one showing her in a dress getting out of a car and the other in her Clowns uniform getting off the team bus-in the July 1953 Ebony is accompanied by the caption, "Dressed in street clothes, Toni Stone is an attractive young lady who could be someone's secretary, but once in uniform she is all ball player."

The article included an explanation from Stone of how she handled herself amid a group of men: "At first, the fellows made passes at me, but my situation in traveling around the country with a busload of guys isn't any different from that of the girl singers who travel with jazz bands. Once you let the guys know that there isn't going to be any monkey business, they soon give you their respect."

Also in July of 1953, Our World had a feature on Stone and reported, "The second baseman of the triple-pennant winning Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League wears a size 16 dress. That is, when she is not playing baseball. On the playing field she wears an oversize 42 shirt (to accommodate her 36 bust) and thinks, talks, and plays like a man."

The Ebony article added, "While most sports fans were sure that the Clowns signed Toni merely as an extra box-office attraction (the team features baseball comedy and 'Spike-Jones like' music on its barnstorming tours), the young lady has surprised everybody by turning in a businesslike job at both second base and at the plate. In her first game against a semipro team in Elizabeth, N. C., she walked and then drove in two runs with a sharp single."

All information about Stone listed her age as 22, 10 years younger than she was. Finneman says that part of the campaign to promote Stone included exaggeration of her schooling, claiming she had a master's degree when, in reality, she did not even graduate from high school.

Stone said she would get dressed in the umpires' room. In the games she did play (approximately 50 out of the 175 the Clowns played in 1953 and usually in non-league games), she normally came out by the middle innings, giving her a chance to shower and change back into street clothes before the rest of the team came in.

It has been reported that Stone once got a hit off Satchel Paige in an exhibition game in Omaha on Easter in 1953. Paige was at this time a member of the St. Louis Browns of the American League. However, on April 5 (Easter), the Browns were in Texas and did not play the Indianapolis Clowns in Omaha or anywhere else. A check of the St. Louis newspapers in March and April of 1953 shows that the Browns did not play any exhibition games against the Clowns in spring training that year. It is possible that Stone faced Paige at another time, although it is not clear whether such a matchup ever occurred.

After the 1953 season, Stone's contract was sold to the Kansas City Monarchs. Her spot in the Indianapolis infield was taken by another woman, Connie Morgan, and the Clowns added another woman, pitcher Mamie "Peanut" Johnson.

Following the 1954 season, Stone retired from professional baseball, her two-year batting average in the Negro Leagues estimated at .243. She continued playing amateur baseball for many years, and then cared for her husband, A. P. Alberga, until his death in 1987 at the age of 103.

A play was already being produced at the time of Stone's death, on November 2, 1996, and opened the following spring at the Great American History Theater in St. Paul. Later that year, "Tony [sic] Stone Field" was dedicated at the Dunning Field Complex, part of the Rondo neighborhood in which she had grown up in St. Paul.

In her 1991 interview with the San Francisco Chronicle, Stone recalled being shunned by teammates who told her to "go home and fix your husband some biscuits." But she also remembered kinder teammates, such as Al Lombardi on the New Orleans Creoles, in whom she could confide. "A woman has her dreams, too," she told Lombardi. "When you finish high school, they tell a boy to go out and see the world. What do they tell a girl? They tell her to go next door and marry the boy that their families picked for her. It wasn't right."

"A woman can do many things."

March 2012 response courtesy of the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) Projecthttp://sabr.org.