Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

What is your opinion of the experiment done by John Howard Griffin where he changed his skin to learn what it was like to live as a black man in Mississippi?

--Haley Johnson - Biloxi, Mississippi

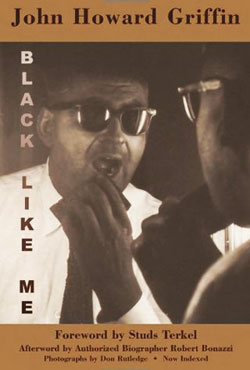

I consider John Howard Griffin's experiment and his resulting book important contributions to the Civil Rights movement; and, given the daily terrorism faced by southern blacks in the late 1950s, one could argue that his actions represented either great bravery or dangerous naiveté. Griffin wrote about his experiences in his autobiographical memoir, Black Like Me.

I was a sophomore at Mattie T. Blount High School when I first read Black Like Me. It detailed his racial journey. Griffin, the author and main character in the book, was a middle-aged white man living in Mansfield, Texas in 1959. He had long been committed to social justice and demonstrated an appreciation for the plight of marginalized groups. For example, as a 19-year-old he worked as a medic in the French Resistance: as part of his service, he helped Austrian Jews escape from the Nazis. Injuries sustained during the Second World War resulted in blindness, a disability he lived with for more than a decade. This was his first experience living as “The Other,” though it was in a pitied minority, not a hated one. By 1959, he was a published author, with a focus on race relations. In his thirties, he had become increasingly concerned about race relations in the United States and frustrated by the lack of understanding between blacks and whites. In his words,

“How else except by becoming a Negro could a white man hope to learn the truth? Though we lived side by side throughout the South, communication between the two races had simply ceased to exist. Neither really knew what went on with those of the other race. The Southern Negro will not tell the white man the truth. He long ago learned that if he speaks a truth unpleasing to the white, the white will make life miserable for him.”1

Griffin, frustrated at the racial tensions that existed between blacks and whites, made the decision to become what sociologists call a complete participant. He decided to undergo medical treatment to temporarily change the color of his skin. His wife okayed the experiment, as did George Levitan, the editor of Sepia (a black-themed magazine) – though Levitan’s initial reaction was, “It’s a crazy idea. You’ll get yourself killed fooling around down there.” Levitan agreed to fund the project in return for the rights to an article about it. By the way, Levitan, though he owned several black-themed magazines, was a white man.

On November 1, 1959, Griffin arrived in New Orleans, Louisiana. He checked into the Hotel Monteleone in the French Quarter. He walked the streets, reminiscing about his previous visit to New Orleans when he had been temporarily blind. He made a resolution: He would not “act” black, meaning he would not act in a way that the society believed that blacks behaved. He would not affect an accent. And, he would not lie. In his words:

“I decided not to change my name or identity. I would merely change my pigmentation and allow people to draw their own conclusions. If asked who I was or what I was doing, I would answer truthfully.”

He went to several establishments, ate at a posh restaurant, and wondered what would happen after he darkened his skin. Would he still be treated with respect? It is clear that he was having second thoughts and that he considered not going forward.

The next morning he met with a prominent dermatologist, explained his experiment, and asked for assistance. The doctor reluctantly agreed to help. In a later meeting, the physician revealed to Griffin his beliefs that light-skinned blacks are more moral than darker blacks and that all blacks are inherently violent. The doctor also fretted about aiding Griffin. Nevertheless, after consulting with several colleagues, he recommended this approach: a medication taken orally followed by huge doses of ultra-violet rays – this treatment was similar to the way vitiligo (a disease that causes white spots to appear on the face and body) was managed. He began treatment immediately.

Griffin began walking through some of the black sections of town, especially in the South Rampart-Dryades Street area. After several days of trying to make a “Negro contact” he met a shoe shiner named Sterling Williams, who Griffin described as “keenly intelligent and a good talker.” Interestingly, Griffin also used this phrase in his book in reference to Williams, “the shine boy [emphasis mine] was an elderly man.” In any event, they became friendly, and Williams helped Griffin transition from a white man to a black man.

Griffin shaved his head. After more intense ultraviolet rays and the application of a skin dye, his appearance was changed, and he did not initially handle it well:

“Turning off all the lights, I went into the bathroom and closed the door. I stood in the darkness before the mirror, my hand on the light switch. I forced myself to flick it on. In the flood of light against the white tile, the face and shoulders of a stranger – a fierce, bald, very dark Negro – glared at me from the glass. He in no way resembled me. The transformation was total and shocking. I had expected to see myself disguised, but this was something else. I was imprisoned in the flesh of an utter stranger, an unsympathetic one with whom I felt no kinship. All traces of the John Griffin I had been were wiped from existence. Even the senses underwent a change so profound it filled me with distress ... The completeness of this transformation appalled me.”

When, as a teenager, I read these words I was offended. I did not see his panic as resulting from a loss of personal identity; I saw it as a harsh rejection of blackness. It seems likely that even a racial liberal in the 1950s might harbor anti-black beliefs and attitudes. Words matter. His use of the word fierce indicates that I might not have been wrong. I mean, what does a fierce Negro look like? His use of words and phrases like shocking, imprisoned, utter stranger, and appalled also suggest an honest and bigoted reaction to looking like the Despised Other. Griffin went on to say, “The worst of it was that I could feel no companionship with this new person. I did not like the way he looked.” I suppose that Griffin’s panic reaction would have been less offensive to me had he permanently changed his skin.

Thankfully, Griffin calmed down and began his six-week experience. He confided his secret to Williams, who offered to help, including allowing Griffin to work with him at his shoe shine stand. There, he got his first real glimpse of what it meant to be black. He was treated as a non-person by many of the whites whose shoes he shined. Indeed, they only looked at him when they asked if he could help them find black girls for sex. He learned the difficulty of finding places to eat and urinate. He recounts meeting a black man who told of hating the ghetto so much that he sometimes went to white neighborhoods to smell the clean air and look at the pretty houses.

Once he was followed by a white man who cursed and threatened him. Griffin tried to get away but the man continued to hound him with racial taunts and threats. Finally, Griffin was left no choice but to defend himself – he was a trained martial artist – but at the last minute the man backed away. For the first time in his life, he felt the sting of being called a nigger.

He tried to get a job but no white employer considered him competent or trustworthy. He battled frustration. While sitting on a park bench a white man told him that he should move. At first Griffin believed the man was trying to protect him from inadvertently violating Jim Crow customs; later he realized that the man simply did not want to sit near him. He also experienced rude treatment from bus drivers, restaurant workers, and others. Living as a black man in New Orleans was bad, but Williams convinced Griffin that things were worse in Mississippi and other southern states.

Griffin traveled on Greyhound buses (and occasionally hitchhiked) across Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia trying to see race relations through the eyes of a black man. And what did he find? He found what every southern black person already knew: the Deep South had a racial hierarchy with whites on the top and blacks on the bottom. He had anticipated some prejudice and hardship, but he was shocked at the extent of it. The little courtesies and amenities that he, as a white man, had taken for granted were now prohibited to him. For example, he couldn’t find a restroom that blacks could use. It was impossible to find a job, suitable housing, or a clerk who would cash his checks. He was threatened. Everywhere he went whites treated him with disdain, fear, or vulgar curiosity. Griffin was particularly shocked when white men openly and without embarrassment asked questions about his sexual life, including one man who asked to see his genitalia. In general, Griffin met blacks who were poor, powerless, and resentful of whites, and whites who treated blacks as second-class citizens. After only a few weeks as a black man, he felt depression and hopelessness – this is a powerful testament to the impact that racial prejudice and discrimination had (and has) on non-white people in this country.

After several weeks, Griffin stopped taking his medication and using the skin dye and began alternating his racial appearance. He would visit a place as a black man and then return as a white man. Not surprisingly, when he presented as a white man, whites treated him respectfully and blacks were standoffish; when he presented as a black man, blacks treated him warmly, while whites treated him with contempt. Griffin concluded that the racial gulf between southern blacks and whites made meaningful dialogue necessary, though highly unlikely.

Six weeks into the experiment, Griffin decided to end the project and return home. He was emotionally spent. Of course, unlike real blacks, he had always had the option to “stop being black” and reclaim life as a white person. Even so, the experience had shaken him. He had received psychological relief by alternating his racial appearance, but he simply could not continue the experiment. He had enough qualitative data to write “Journey into Shame,” a five-part series of articles for Sepia, which was an indictment of the Jim Crow South and the system of discrimination that denigrated blacks. During his experiment, he had taken notes. Later, Griffin rewrote his notes in the form of journal entries, and subsequently published the entries as Black Like Me.

He became a national celebrity and villain. He was interviewed on national television shows and in newsmagazines, including Time. His unconventional approach to understanding race relations brought him congratulatory mail from around the world; however, in his home town of Mansfield, Texas, the reaction was different. He and his family were subjected to hate threats, including one to castrate him. An effigy of him, painted half black and half white, was burned on Main Street. A cross was burned in the school yard of an all-black school. The threats convinced Griffin to move his family to Mexico. For those who opposed civil rights for blacks, Griffin was a race traitor. He received hate threats for the rest of his life.

Griffin became a prominent human rights activist. He worked with Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., Dick Gregory, Saul Alinsky, and NAACP Director Roy Wilkins trying to secure civil rights for blacks. Griffin, a dynamic orator, taught seminars at the University of Peace with Nobel Peace Laureate Father Dominique Pire, and delivered hundreds of lectures worldwide. Although he spoke before many and varied audiences, his greatest contribution was probably his impact on white audience members, who, in many instances, accepted for the first time the simple truth that blacks, especially those in the Deep South, were daily treated as a despised lesser caste.

One final note: Griffin died on September 9, 1980, from complications of diabetes. It is often incorrectly claimed that his death resulted from the procedures he used to darken his skin. For me, Griffin was a courageous freedom fighter, and his work was seminal in the struggle to gain first-class citizen rights and privileges for blacks – and, by extension, all despised groups. I recommend Black Like Me to all our readers. I also recommend this short YouTube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DPP_n6cE_TA.

1Click here to read the first section of John Howard Griffin’s, Black Like Me.

May 2011 response by

David Pilgrim

Curator

Jim Crow Museum