Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

I would like to know more about Otis Vaughn, the man who donated his sizeable collection to the Jim Crow Museum.

--Stephanie Jenkins - Houston, Texas

One of the persons responsible for my admission into graduate school at The Ohio State was Dr. Frank W. Hale, then-associate dean and chairman of the Fellowship Committee of the Graduate School. While I was there, he was a friend and mentor. A quarter of a century later, Dr. Hale graciously accepted my invitation to come to Ferris to give a lecture. After he toured the Jim Crow Museum he noted that he knew a family (the Vaughns) that had a similar collection. Dr. Hale left a video, In the Belly of the Ship, for me to watch. The video was my first introduction to Mr. Vaughn and his collection.

As I watched the video, I was reminded of the bond that often exists among collectors of contemptible collectibles. That bond is hard to explain. I know what it is like to explain to friends why racist objects are in your basement, your family's home. I know the dread of discussing a contemptible piece with a dealer who sees the object as just another piece of merchandise, or worse, sees it as "cute" or "funny." Has there ever been a collector of this material – one who did not intend to resell the objects – who did not hate spending good money for the pieces? But most of all, I know what it is like to drive hours to get to a flea market, all the while warring with the simultaneous, conflicting feelings of hoping to find a piece worthy of the drive and anger and disgust at finding that piece. I know these things and so did Mr. Vaughn.

Mr. Vaughn was born in Yazoo City, Mississippi on October 14, 1922. You do not have to be a historian to realize that life for blacks on the Mississippi Delta in the 1920s was harsh. In the 19th century, white farmers in search of fertile farmland came with their slaves and created a plantation system. The slaves did the backbreaking work that made the Mississippi Delta the richest cotton-farming land in the United States. After slavery ended, Mississippi ranked as one of the most repressive states for African Americans, who found themselves systematically locked into poverty and locked out of opportunities for educational, social, and political advancement. Moreover, southern blacks, in the early decades of the 20th century, lived in daily fear of being arrested, beaten or lynched if they complained about or tried to improve their social conditions.

Mr. Vaughn picked his first hundred pounds of cotton on his 10th birthday. Although it was not his last day in the cotton fields, it was the day that he resolved to not spend his life as a field hand. When he could, he worked as a bricklayer's helper, and quickly mastered the bricklaying trade. He described his life in Mississippi in this way, "Most of my life was lived from the back of a bus." Faced with the prospects of a life of poverty as a cotton-picking field hand in a rigidly segregated place, Vaughn left the Deep South and eventually settled in Columbus, Ohio, where he developed a successful masonry contracting business.

In his 60s, Mr. Vaughn became obsessed with documenting the history of Africans and their American descendants. He feared that the true experiences of blacks would be lost unless he and other African Americans collected and preserved the artifacts related to black history in Africa and the United States. From about 1982 until his death in 2003, Mr. Vaughn amassed a large collection of objects depicting the African American experience – from the shores of West Africa through the American civil rights movement. He kept his collection in the basement of his home. He had two names for his collection, "The Yazoo Room," and "The Belly of the Ship."

Similar to the Jim Crow Museum's holdings, Mr. Vaughn's collection included many objects that defame and belittle African Americans: slavery-era objects, Mammy and Tom cookie jars, postcards with black children portrayed as food for alligators, metal tins with caricatured images of blacks, "Jolly Nigger" banks, segregation signs, and other contemptible collectibles. Mr. Vaughn did not limit his collection to objects that disparage blacks; he also collected objects that show the accomplishments of African Americans such as African art, Negro Leagues memorabilia, and busts and statues of black civil rights leaders, entertainers, athletes and scholars.

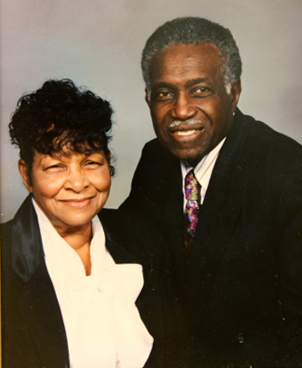

I regret that I never met Mr. Otis Vaughn. We would have had great conversations. My knowledge of him comes from watching In the Belly of the Ship, and conversations with his children, Michael and Beverly. Maybe it is presumptuous to believe that we were kindred spirits, but I do share his obsession with using objects to document the black experience in this country and I am committed to making sure his collection and legacy live on through the Jim Crow Museum.

April 2011 response by

David Pilgrim

Curator

Jim Crow Museum