Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

I have always liked identifying famous firsts. Who was the first black person to conduct a (symphony) orchestra in the United States?

-- Stephanie Onis - Sacramento, California

The answer is Henry Jay Lewis, who in 1968 became the conductor and musical director of the New Jersey Symphony. A brilliant musician, Lewis later conducted nearly every major American orchestra — the Boston Symphony, the Chicago Symphony, the New York Philharmonic, the Cleveland Orchestra — as well as international orchestras and opera companies in cities such as London, Paris, Milan, Copenhagen and Tokyo. He was an especially skilled interpreter of the works of composers Richard Wagner, Richard Strauss, and Robert Schumann.

Lewis was born October 16, 1932, a difficult period in history for Black Americans. The Great Depression had left many Americans financially broken and psychologically defeated. No group was harder hit by the Great Depression than African Americans. By 1932, approximately one-half of Black Americans were unemployed. The Blacks who had jobs were mostly in low-paying, menial work, and even this employment was resented by Whites who demanded that Blacks be fired from any jobs as long as Whites were unemployed. Not surprisingly, racial tension and violence increased; the lynchings of Blacks, which had declined to eight in 1932, increased to 28 in 1933.

All that said, Lewis was a fortunate child in many ways. He was born and reared in Los Angeles, a relatively liberal city, and, thereby, avoided the harsh, thick, life-limiting segregation that Blacks experienced in the South and in smaller cities in the North. Moreover, unlike many 1930s Black children, he was not reared in poverty. He was the only child of Henry J. Lewis, an automobile dealer, and Mary Josephine Lewis, a registered nurse. Also, his musical gifts were recognized early and encouraged, such that, by age five, he was receiving piano lessons. In parochial and, later, in public schools, he played with amateur orchestras; and as a teen, he performed in solo recitals and conducted both his junior and senior high school orchestras for commencement ceremonies. Lewis studied voice, clarinet and several string instruments, but his real love and talent was the double bass.

At the age of sixteen, Lewis joined the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, becoming not only the first Black instrumentalist (a double-bassist) in a major American orchestra, but also the youngest. Lewis's talent and post with the Philharmonic helped win him a full scholarship to the University of Southern California. With little interest in studying music education — the only degree program available in the university's music department — he was not graduated, though he earned enough credits. He remained with the Philharmonic until 1954, when he was drafted into the Army.

He played (again, double-bass) with and conducted the Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra, based in Germany and the Netherlands; he held the conductor position until his discharge in 1957. Lewis returned to the United States and founded the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra; he received national attention for taking that orchestra to perform in Europe. Lewis gained greater national recognition in 1961 when he was appointed assistant conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra under the famed conductor Zubin Mehta, a post Lewis held from 1961 to 1965. On February 9, 1961, Lewis became the first African American to conduct a major American orchestra when he took the Los Angeles Philharmonic's podium after the scheduled guest conductor became ill. In the early- to mid-1960s, Lewis ranked as the outstanding African American conductor in the United States, though he did not have an orchestra of his own.

Lewis’s star was clearly rising. In 1968, at age 36, he beat out more than 150 other candidates to become the conductor and musical director of the New Jersey Symphony. His hiring, noted New York Times writer Robert D. McFadden, "was a landmark event in music, for few blacks had even made it into the orchestra pit, let alone onto the podium. It made national headlines." Over the next eight years, Lewis transformed the New Jersey Symphony from a small community ensemble into a prestigious, top-drawer orchestra with a 100-concert season and performances at Carnegie Hall and the Kennedy Center in Washington. The Orchestra’s home was Newark, a city with large numbers of Black people and low-income people of all hues. Lewis took the orchestra into poor and working-class neighborhoods for outdoor concerts. Many who attended were hearing European classical music for the first time.

On January 7, 1955, Marian Anderson, an African American singer, brought her rich contralto voice to the Metropolitan Opera House, thus becoming the first Black person to perform at the hallowed hall. Seventeen years later, Lewis became the first African American to conduct there — conducting a performance of "La Boheme." Anderson and Lewis were both pioneers.

After retiring from the New Jersey Symphony in 1976, Lewis toured as a guest conductor at the podium of nearly every important orchestra or philharmonic in North America and Europe. He struggled to find permanent employment as a conductor, even though he was, in McFadden’s words, "musically brilliant and a commanding figure with the baton.” Between 1989 and 1991, Lewis was the chief conductor for the Radio Symphony Orchestra in Hilversum, Netherlands.

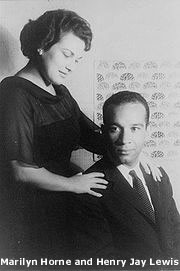

From 1960 to 1979, Lewis was married to famed opera singer Marilyn Horne, who often credits him with her early development as a singer. She considered him her “teacher and right hand.” Horne, one of the preeminent mezzo-sopranos in opera history and arguably the greatest Rossini interpreter ever, had one child, Angela, with Lewis. The couple divorced in October of 1974, but remained friends and sometimes performed together. It should be noted that they were an interracial couple, and a very public one, at a time when interracial relations were taboo in much of America.

Lewis continued to tour as a guest conductor until his death from a heart attack on January 26, 1996, at the age of 63.

January 2010 response by

David Pilgrim

Curator

Jim Crow Museum