Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

Why do you have Memin material in a museum devoted to American racism? Memin is not racist and not American. The so-called Memin stamp controversy is not helped by having Americans who know little about Mexico and its culture sticking their opinions where they do not belong.

--Angel Rodriquez - Los Angeles, California

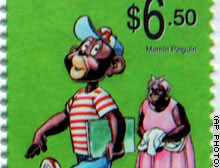

Rather than just reacting to the Mexican government’s recent attempt to honor Memin Pinguin, a popular comic strip character who also looks every bit the pickaninny caricature, with moral outrage we should see it for what it is: an opportunity. The debate over the inherent racism of the stamps and what it says about the Mexican attitude on race is an opportunity to address two issues of race that are becoming increasingly important in the U.S. and around the world. One is the empty idea of racial blindness, particularly in relation to racist images of the past, and how it impedes a true sense of racial understanding. The second is the need to better understand the subtly complicated nature of race and racism in Latin America. Both are important as the ethnic face of the U.S. continues to change and local problems around the world become international ones.

Memin Pinguin is the 58 year-old creation of the late Yolanda Vargas Duche. The character, whose name translates roughly to “Billy the Little Devil,” is something of a Dennis the Menace, a lovable mischief-maker character in name as well as attitude. The series follows Memin’s adventures with his three friends Ernestillo, Carlos and Ricardo (all “white” Mexicans), but the central relationship of the series is between the “negrito” and his mother, Ma’ Linda. In 1947 Vargas Duche returned to Mexico after a period of working in Cuba. She was apparently so inspired by Havana’s many black children that she patterned Memin after them.

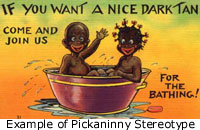

It was seemingly a genuine warmhearted fascination that influenced this decision to make a black protagonist. And yet the fact that nearly all the other characters in the series are rendered in a fairly realistic manner, while Memin is drawn in the highly stylized image of the old cartoon version of a little black pickaninny must raise a few eyebrows and questions. Like the word itself, which comes from the Portuguese slaver term pequenho for “little one,” the pickaninny cartoon image, that has populated popular western media since the 1890s, has international recognition. Ma’ Linda is drawn in a less exaggerated style than her son, but is nonetheless a perfect echo of the black Mammy figure, perhaps more common worldwide than the pickaninny.

Neither character exhibits the worst of the dimwitted mannerisms associated with the black caricatures featured in the many racist American cartoons of the early 20th century. Nevertheless they are totally in line with the Latin American tradition of portraying racialized stereotypes. Memin’s speech and gestures are bombastic, he is lazy when it comes to doing chores, and, as his name implies, he is a troublemaker. These are softened versions of the typical black racial stereotypes in Latin America.

Afro-Latinos are presented in popular culture as loud and uncultured, tremendously lazy and prone to crime or violence. This image, repeats in the popular media and conversation from Ecuador, to El Salvador, and the Dominican Republic in varying degrees. The issue with these stereotypes, like all stereotypes, is not that they are baseless, or that in the case of Memin they are inherently malicious, but rather that absent alternative pictures that show a more complete image these representations start to form the popular conceptions of different groups.

From op-eds and blogs to government officials and the stamp buying public, the Mexican response is one of defiance and annoyance. They see the protest to the Memin stamp as actions by ignorant Americans who know nothing of Mexican culture, and by opportunistic black leaders who are trying to use this to get attention. This opinion holds that the cartoon isn't intended to be offensive to anyone, and therefore it isn’t. If anything, the publishers claim, Memin has improved its readers’ racial sensitivity, that the character’s “exaggerated traits that prove a noble heart is what is important within a person.” As readers follow Memin’s adventures they relate to his love for his mother and his loyalty to friends. By the end they feel so much affection for Memin that this affection somehow translates to all people.

This naïve opinion is not news. It is the same argument used to defend the appreciation of Buckwheat, Amos and Hattie McDaniel’s various Mammy roles, along with other black characters of the Jim Crow era. For whatever humor and humanity these characters brought to audiences they come from an assumption of inferiority and disdain that cannot be ignored. Memin Pinguin is not Buckwheat, but he draws on the same inspiration that created an international visual vocabulary for what it is to be black.

Some argue that cartooning is the art of caricature and requires exaggeration. However, that argument always fails when one compares the variety of exaggerated features we see in white caricatures to the constant big-lipped buck-eyed grimace we find on black caricatures over and over. Dennis the Menace has exaggerated features that are different than Lil’ Abner’s, which are different than Archie’s, but Little Black Sambo looks like 40’s Marvel comic sidekick Whitewash, who looks like, Ebony, the Spirit’s sidekick, who looks like every other Jim Crow caricature. At the least these images demonstrate white artists’ noninterest in making nuanced black images, but at the worst they demonstrate something far more sinister. The fact is the basic composition of the pickaninny drawing came together during the turn of the 20th century just as Jim Crow laws were being codified in the U.S. and the European powers were busy scrambling to carve up Africa into colonies. Whatever humorous and or endearing feelings these images evoked in the buying public they also carried an implicit psychological justification for the morally offensive political programs in which western countries were engaged.

Mexicans may argue that all of that has little to do with their country and their beloved Memin, but regardless of intention, Memin’s appearance is based so heavily on this pickaninny arch-type it can’t help but recall all the negativity of the past. Truly the blindness to that past and its impact on black peoples everywhere is cause for more concern than the simple intention of cartoon character. Although the Mexicans who have rallied to the Memin stamp’s defense like to point out that it is the U.S. that is racist, this grossly ignores their own country’s continuing experience with racism.

Mexico is not alone in this. Many in Latin America share this opinion, that they never had Ku Klux Klansmen lynching black people and thus their societies aren’t racist. Many will admit pervasive classism, but not racism. And yet the correlation between race and poverty levels make that argument hard to accept. In Latin American society racial and economic status are intimately connected.

Unlike the stark racial attitudes of northern Europe, Iberian culture, like their Arab former conquers, has a more fluid but similarly stratified, view of race. The Nordic Anglo-Saxon version of race relations, according to noted Afro-Cuban scholar, Dr. Carlos Moore, holds the “other” as a fearsome subject that must be separated from white society by “a stable racial social order achieved and perpetuated through enforcement of an inflexible two-track system whereby extreme racial polarization is involved between two opposing somatic prototypes.”

The Arab-Iberian model is based on the light-skinned hierarchy without such a rigid fear. Miscegenation here isn’t a source of corruption for Europeans, but rather one of genetic redemption for darker races. As Moore concludes, "in the U.S. one drop of black blood makes someone black. In Latin America one drop of white blood makes you white." This is an important distinction that has played out in Latin America’s racial history.

The detrimental effects of the Spanish and Portuguese conquest of the New World on native American populations is fairly well known here in the U.S. It is less well known that slavery did not just impact North America, Brazil and Cuba, but every colony-made-independent nation in the western hemisphere. Few know about the Indian wars of Uruguay, Argentina and Chile, in which those governments successfully used their remaining slave populations to wage mutually genocidal wars against their respective indigenous populations. Or, that while the Caribbean Islands have the most visible black populations, Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela actually have the largest numbers of black citizens.

In Latin America black people don’t face lynch mobs but rather an all-pervasive, largely unchallenged sense of inferiority. The pressure to blanquearse (whiten oneself) is everywhere as popular media offers very few positive black images outside of sport stars, musicians and beauty queens. Euphemisms like “improving the race” to prefer having kids with a lighter partner, “money whitens,” and “working like a black in order to live like a white,” are ever present. In addition to these cultural pressures are rigid economic barriers to employment opportunities for racial minorities. Except for Brazil, and maybe Cuba, no serious efforts have been made to address discriminatory hiring practices, thus Latino societies can comfortably believe that it is mere coincidence that class divisions largely follow racial divisions.

In truth this situation is not radically different to what has been, and in many ways still is, experienced here in the United States. However, down there, except for a few instances, there has been little political or social pressure to confront these issues. Still, while there are many commonalities in the cultures of Latin countries it would be a mistake to think them all the same.

In the Mexican context, with only 2 percent its population of over 100 million identified as black, there are distinctions. Most of Mexico’s racial marginalization is directed to the country’s large indigenous population. They work most menial jobs and are the primary butt of jokes and social derision, which is ironic considering the country’s place among Latin American nations as one of the most vigorous celebrants of it’s indigenous heritage. Statues and paintings of Mayan, Aztec and Tarascan kings adorn plazas in the same cities where modern day indigenous menial laborers aren’t allowed into certain restaurants.

Mexico’s relation to it’s unique, and often ignored, African heritage is equally contradictory. Black slaves from Spain arrived in Mesoamerica shoulder to shoulder with Hernando Cortez and the first conquistadors, and as the colony grew so did the African slave population. Colin A. Palmer, of Princeton University, estimates that 200,000 slaves were brought to Mexico during the Neuva Espana colonial period, with their population ranging from about 10 to 35 thousand at any one time. He continues:

“African labor was vital to the Spanish colonists. As indigenous peoples were killed or died from European diseases, blacks assumed a disproportionate share of the burden of work, particularly in the early colonial period. African slaves labored in the silver mines of Zacatecas, Taxco, Guanajuato, and Pachuca in the northern and central regions; on the sugar plantations of the Valle de Orizaba and Morelos in the south; in the textile factories ("obrajes") of Puebla and Oaxaca on the west coast and in Mexico City; and in households everywhere. Others worked in skilled trade or on cattle ranches.”

The first black Mexican to be declared a national hero, more than 300 years after the fact, was Gaspar Yanga, who in 1570 led a sugar plantation slave revolt in what is now the state of Veracruz. He and 500 other escaped slaves ultimately founded a small town in mountains west of Veracruz. Over the next 30 years they fought off all attempts at incursion into the territory until 1806 when the Spanish were forced to sign a treaty with Yanga making the town named after him one of free people.

Two of the most important heroes in the struggle for Mexican Independence, Jose Maria Morelos and Vincent Guerrero, were mulattos of humble origins who rallied large swaths of African, Indigenous and mixed blood Mexicans to keep the cause alive at some of its lowest moments. Guerrero went on to become the country’s second president in 1829. A fiercely liberal populist, he abolished slavery in Mexico but his term was cut short when he was ousted by a conservative coup. Today, both heroes’ respective African roots are ignored, and or, dismissed.

Though the original African populations of Mexico have largely mixed in with the general population, there is still a visibly strong presence in towns, including Yanga, throughout the state of Veracruz, as well as along the Costa Chica region in the states of Oaxaca and Guerrero (a state named after its famous son Vincent Guerrero). There are also strong Pan Afro-American roots in the northern Mexican state of Coahuila where a group of black Seminoles settled after being chased from Florida, Oklahoma and Texas in the mid 1800s.

Despite the often central roll played by African descended peoples in Mexico’s history many Mexicans believe their country had only had a handful of slaves, if any, who certainly have little to do with Mexico today. This cultural amnesia returns us to the current Memin stamp controversy. The focus thus far has been between Mexicans and Black Americans, but the fact is we have very little to do with the issue. Memin Pinguin is not maliciously racist like the many Sambo stories the U.S. produced earlier in the century. Had he been drawn with less nostalgia for that racist caricature we might be hailing the strip today as an example of the commercial potential of black characters among very broad audiences. But that troubling appearance, and the inability of what seems to be a majority of Mexico to even partially understand the offense it represents, demonstrates how far they have to go to truly come to terms with their heritage and all the parts of their diverse society.

When Mexican officials claim the stamp could offend no one, they tellingly ignore Afro-Mexican voices that have been protesting since the stamp was announced. Afro-Mexican pop singer Johnny Laboriel is one such voice who on June 30th said, “Of course people are going to be offended by the caricature…they do this without thinking of the consequences.”

That sentiment was echoed by La Asociacion Mexico Negro, which represents some 50,000 blacks of the Costa Chica region, who while demanding an apology stated, “Memin Pinguin rewards, celebrates, typifies and cements the distorted, mocking, stereotypical and limited vision of black people in general.” A representative from the group, Rev. Glyn Jemmott of El Ciruelo, a black village in Guerrero, elaborated, "The stamps are 101 percent offensive, there is no doubt about it. What is evident is the level of tolerance of racism that exists in the country. We are accustomed to racism to the point where anyone who dares question it runs the risk of being considered unpatriotic."

Though they receive little to no exposure, such Afro-Latino groups, from Brazil to the Andean nations and the Spanish speaking Caribbean are alive and growing. They are working hard to fight for civil rights and make their children proud of their black heritage. These groups need our help to make their voices heard and their concerns addressed.

The issue for African-Americans in the U.S. should not be a personal offense over a perceived insult. We are peripheral to the entire issue, really. The real problem is the reaffirmation of a government sanctioned Afro-Latino inferiority generally, and the invisibility of Afro-Mexicans specifically. We should use this occasion not to organize protests directed at all of Mexico out of hurt feelings, but instead build stronger bridges of solidarity with Afro-Mexicans and other Afro-Latinos.

As America becomes more Latinized, American marketers and politicians are trying to figure out how to take advantage of the displacement of the Black race as the most influential minority in favor of the Latin/Hispanic race. But we need to realize that the “Hispanic race” is an American construct that scarcely exists south of the border. The racial matrix of relationships between black, white and American Indian is the foundation of social orders throughout the western hemisphere. The specific may vary but this common base is a point from which to develop relations. It is no longer simply anthropological curiosity or afrocentric novelty that compels us to learn more about our brothers to the south but rather political necessity. If we don’t develop that knowledge, we will always wonder where exactly the Vincente Foxes of the world are coming from when they comment on what “even blacks” will or won’t do. More pertinently, we will lose an important, and natural, ally for improving opportunity and equality for all in the Americas.

February 2010 response by

Troy Peters

Troy Peters, the author of this essay, is a Policy Fellow at the Campaign for America's

Future, a progressive political institute based in Washington, DC. The Jim Crow Museum

thanks The Black Commentator for granting permission to reprint this essay, which originally appeared at

http://www.blackcommentator.com/147/147_guest_peters_pickaninnies.html