Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

I am a high school junior doing research on people who influenced Dr. King. We are supposed to pick a person who is not really famous. So, I cannot use Mr. Gandhi. Could you suggest someone?

--Allison Wright - Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

“Over and over we must know that the real target of evil is not the destruction of the body, the reduction to rubble of cities; the real target of evil is to corrupt the spirit of man and to give to his soul the contagion of inner disintegration. To drink in the beauty that is within reach, to clothe one's life with simple deeds of kindness, to keep alive sensitiveness to the movement of the spirit of God in the quietness of the human heart and in the workings of the human mind -- this is, as always, the ultimate answer to the great deception." Howard Thurman

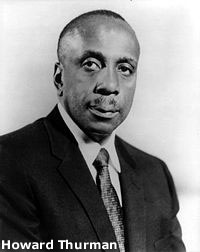

Because the “not really famous” limitation is a subjective matter, I will suggest Howard Thurman, a theologian, educator, peace activist, and civil rights worker. He was a prolific writer and the co-founder of America's first interracial Christian church, Church of the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco. Although Thurman had a profound spiritual impact on King and on many other civil rights leaders, his contributions have often been overlooked. I consider him a “famous” historical figure; however, it has been my experience that many Americans—sans students of African American history—know little or nothing about him.

Thurman was born in Daytona Beach, Florida in 1899. This was a period when most of the southern and border states (and some northern cities) were hastily passing laws to deny African Americans basic rights. Indeed, only three years earlier the United States Supreme Court had passed Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), a landmark and infamous decision which upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation in public accommodations under the doctrine of "separate but equal.” Of course, the public accommodations were never equal. The passing of the Plessy decision meant that states like Florida and cities like Dayton Beach had their segregation policies legally, politically, and socially legitimated by the federal government.

Howard Thurman and his two sisters, Henrietta and Madeline, were born to hardworking but poor parents, Saul and Alice. Saul died when his son was only 8 years old. This left Alice and her mother, Nancy Ambrose, as the primary caregivers for the children. Howard developed a strong bond with his grandmother, in part because he could read and “Grandma Nancy” could not. He would read the Christian Bible to her and she would interpret the scriptures with him. Years later, Thurman would be known for his deep and layered understanding of religious scriptures and would attribute the foundation for his understanding to the many times that he and his grandmother studied the Bible together. She also instilled in him ideas about egalitarianism and social justice based on Christian principles.

Thurman was an intelligent child and an excellent student but the public school system in Daytona Beach had no provisions for African American students to get formal education beyond the 7th grade. In other words, there was no 8th grade schooling for Black children and, therefore, reasoned the public school officials, no need for a high school for Black students. Several Black teachers argued that Thurman should be offered the opportunity to learn the 8th grade curriculum through independent study. Their plea was accepted; this was remarkable given the racial climate—though one could cynically argue that the White school officials believed that no child, especially a Black student, could pass the 8th grade examination without classroom instruction. Thurman passed the exams, personally administered by the White school superintendent and became the first African American to receive a high school degree in Daytona Beach.

In 1923, Howard Thurman was graduated valedictorian from Morehouse College. In 1925, he was ordained a Baptist minister after completing study at the Colgate Rochester Theological Seminary (Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School). His first pastorate, at Mount Zion Baptist Church in Oberlin, Ohio, was followed by a joint appointment as professor of religion and director of religious life at Morehouse and Spelman colleges. Thurman spent the spring semester of 1929 studying at Haverford College with Rufus Jones, one of the most influential Quaker historians and theologians of the 20th century. Jones was leader of the pacifist, interracial Fellowship of Reconciliation. Thurman earned his doctorate at Haverford.

Thurman was the first dean of Howard University’s Rankin Chapel, where he served from 1932-1944. In 1935, Thurman led an African-American Christian delegation to South Asia. In India, he and his wife met Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, the spiritual leader and advocate of satyagraha—resistance to tyranny through mass civil disobedience. They talked about oppression, freedom, and nonviolence. Gandhi, a spiritual leader of India during the Indian independence movement, convinced Thurman that African Americans could best overcome racial injustice by embracing a non-violence approach that grew out of deep spiritual convictions.

The meeting with Gandhi had a profound impact on Thurman, who began reflecting on how the life and teachings of Jesus were relevant for oppressed people, including Blacks struggling against racial prejudice and discrimination in the United States. More than a decade later, Thurmond’s ideas crystallized in Jesus and the Disinherited (1949). In this book he used the New Testament gospels to lay a foundation for a nonviolent civil rights movement. Thurman’s great passion for a spiritually-centered life and compassion for oppressed people are evident in Jesus and the Disinherited. For Thomas, Jesus’ life was the model for those who wanted social change. I am not a theologian and I do not want to misinterpret Thomas’ views, but I believe his message can be summarized in this way: You cannot change a corrupt system if you yourself are corrupt; one must change on the inside to change the external world. Jesus’ life was spent helping downtrodden, marginalized people spiritually change. This change would empower them to both survive in the face of oppression and change their oppressors and oppressive systems.

According to some reports, King carried Jesus and the Disinherited when he marched during civil rights protests. It is clear that King accepted the ideas of Ghandi and Thurman regarding the usefulness of nonviolence as a way to overcome evil systems and oppressive people.

In 1944, Thurman left Howard University to help the Fellowship of Reconciliation set up the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco, California. It was the first racially integrated, multicultural Christian church in the United States. Thurman brought people of every ethnic background together to worship and work for peace. Thurman saw it as a religious community in which there would be "neither male nor female, White nor Black, Gentile nor Jew, Protestant nor Catholic, Hindu, Buddhist, nor Moslem, but a human spirit stripped to the literal substance of itself.” He served as co-pastor with a White minister, Dr. Alfred Fisk. Thurman was then invited to Boston University, where he became the first African American Dean of Marsh Chapel (1953-1965). Thurman was the first Black person to be appointed a tenured Dean of Chapel at a predominantly White university.

When Thurman arrived at Boston University he formed a close relationship with King, a doctoral student in the last year of his studies at the University. In There Is a Balm in Gilead, Lewis Baldwin quoted King's friend, Dr. Philip Lenud, as saying, “(Thurman) had a personal, spiritual influence on Martin that was so lofty, and that helped him to endure. The spiritual and moral energy Thurman generated influenced him so much." King admired the older minister as a sage and embraced not only Thurman’s ideas about nonviolence, but also grew to see the potential role of Christian churches in social justice efforts. Not surprising, the American civil rights movement was deeply wedded to southern Black churches.

The relationship between the elder Black preacher and his young protégée did not diminish when King left Boston University. Although Thurman did not participate in protest demonstrations he was an advisor to King and other civil rights leaders. In correspondence and meetings, Thurman supported King's efforts, but urged him and other civil rights leaders to maintain their spiritual roots: meditation, prayer, singing, celebration, and worship. He urged them to be as vigilant in their spiritual journeys as they were in their social justice efforts. Until his death in 1981, Thurman continued to believe that social change would only come through personal transformation and adherence to spiritual disciplines.

I started this essay with comments about Thurman’s fame or lack thereof. The truth is this: Thurman cared little about personal accolades. In many ways, he was an old-fashioned preacher groomed by a seemingly incongruent plethora of circumstances and people—poverty, racism, southern Black Christians, southern White Christians, a Quaker mystic, an Indian Mahatma—who grew to become a spiritual mentor for King. He was an idealist who believed that social change and social justice were possible, and he was a deeply religious man. So, I will use a scripture from the Christian Bible to summarize his life, "You have been told, O man, what is good, and what the Lord requires of you: Only to do the right and to love goodness, and to walk humbly with your God." (Micah 6:8, New American Bible).

Thurman wrote 20 books, many of which are now being re-released. That is good. And so, I will conclude with a quote from Thurman that is dear to my heart because it speaks to me both personally—as I wrestle spiritually—and professionally, as I try to matter as a Chief Diversity Officer. The quote is from his book, The Search For Common Ground: An Inquiry Into The Basis Of Man's Experience Of Community (1971).

"In the conflicts between man and man, between group and group, between nation and nation, the loneliness of the seeker for community is sometimes unendurable. The radical tension between good and evil, as man sees it and feels it, does not have the last word about the meaning of life and the nature of existence. There is a spirit in man and in the world working always against the thing that destroys and lays waste. Always he must know that the contradictions of life are not final or ultimate; he must distinguish between failure and a many-sided awareness so that he will not mistake conformity for harmony, uniformity for synthesis. He will know that for all men to be alike is the death of life in man, and yet perceive harmony that transcends all diversities and in which diversity finds its richness and significance."

April 2010 response by

Dr. David Pilgrim

Curator

Jim Crow Museum