Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

If you did your homework you would find that the lawn jockey is something that black people should be proud of and you wouldn't have lawn jockeys in a museum of racism. Next, you'll be saying that people are racist who have lawn jockeys.

-- Dublin Hayes, Dexter, Missouri

I believe that by "something that black people should be proud of" you are referencing the supposed origin of the black lawn jockey called Jocko. There are several variations of the story; below is a popular account offered by the River Road African American Museum in Louisiana.

"The story begins the icy night in December 1776 when General George Washington decided to cross the Delaware River to launch a surprise attack on the British forces at Trenton. Jocko Graves, a twelve-year-old African-American, sought to fight the Redcoats, but Washington deemed him too young and ordered him to look after the horses, asking Jocko to keep a lantern blazing along the Delaware so the company would know where to return after battle. Many hours later, Washington and his men returned to their horses that were tied up to Graves, who had frozen to death with the lantern still clenched in his fist. Washington was so moved by the young boy's devotion to the revolutionary cause he commissioned a statue of the 'Faithful Groomsman' to stand in Graves's honor at the general's estate in Mount Vernon." 1

I have heard this account from many African Americans and it is frequently cited on Internet sites. It is a heroic tale and, like many such tales, its historical accuracy is questionable. In a 1987 letter to the Enoch Pratt Free Library, Ellen McCallister Clark, a Mount Vernon librarian, concluded that "the story is apocryphal; conveying a message about heroism among blacks during the Revolutionary War and General Washington's humanitarian concerns, but it is not based on an actual incident. Neither a person by the name of Jocko Graves, nor the account of any person freezing to death while holding Washington's horses has been found in any of the extensive records of the period. Likewise, the Mount Vernon estate was inventoried and described by a multitude of visitors over the years and there has never been any indication of anything resembling a 'jockey' statue on the grounds. I have put the story in the category with the cherry tree and silver dollar, fictional tales that were designed to illustrate a particular point." 2

Many of the heroic deeds done by Africans and their American descendants were ignored in the history books that lined this nation's shelves in the 19th and 20th centuries. This neglect was frequently intentional, designed to buttress the idea that Blacks were deficient in all important ways. Despite this, the creation and acceptance of Jocko stories are ways for African Americans to say, "We were always brave, always worthy of inclusion, even admiration." 3 It is a good story, a chest-puffer; however, there is no evidence that the Jocko legend is true.

I am willing to wager that most people who have black lawn jockeys in their yards have never heard of Jocko Graves or the stories about him. These black-faced, racially caricatured lawn ornaments were not purchased to celebrate the bravery of a little boy, let alone represent the bravery of a people. So, why are they in people's yards? Some people inherit them, as I have come to learn from many owners of black lawn jockeys. Others see the lawn jockeys as cute -- though I must confess that when someone describes the black-faced objects as cute, I throw up both my hands. Some people like Schlock gardens that include traditional lawn warts: garden gnomes, concrete geese, pink flamingos, black lawn jockeys, and other aesthetically questionable objects. And, of course, there are always Americans who own controversial objects as a way of saying, "No one tells me what to do and no one tells me what not to do." Personal liberty is, after all, one of our core values.

The Jocko story has another chapter which is almost as remarkable as its creation account, and this one seems slightly more plausible. Charles Blockson, a historian and collector of Underground Railroad artifacts, claims that from the late 1700s through the Civil War, lawn jockeys were used to warn escaped enslaved individuals of danger or to signal that a building was a safe house. 4 A brightly colored ribbon or fabric tied to the statue's arm or a lighted lantern affixed in its hands sent messages to enslaved runaways: red meant danger and green, safety.

A problem with this account, however, is that the use of red and green as signal colors dates back to World War I railroad signals, long after the late-1700s as suggested by Blockson. Nevertheless, it is possible that enslaved runaways and their supporters used red colors to indicate danger and green colors to mean it was safe to stop. After all, it only needed to be understood by enslaved runaways and their helpers, and any agreed upon signals could work. For example, a scarf of any color around the jockey's arm might mean safety.

Another potential problem with this story is that enslaved runaways often traveled at night and the darkness would have made it difficult to see different shades of cloth; difficult, to be sure, but not impossible. Frankly, no system for escape was without problems for the enslaved. If an enslaved person had to get precariously close to a home to see the signal, well, that is what he or she had to do. And, though it was not preferred, some enslaved runaways traveled in daylight. Of course, a signal would have been easy to send by lighting a lantern and placing it in the hand of the lawn jockey so that light-off might have meant that the house was full and had no more room for runaways. I do not doubt that a black-faced lawn ornament was used as a signal to the enslaved. After all, there had to be ways to send otherwise cryptic messages to runaways, and given that slavery lasted more than two hundred years, it is likely that it happened at least once. Nevertheless, there is little evidence that this practice was widespread.

At the risk of being polemic, are the families that have black-faced lawn jockeys honoring the enslaved who fled for their lives or the families that aided them? I doubt it. The contemporary families who own and display lawn jockeys have most likely not heard of Jocko Graves or the stories about lawn jockeys and the Underground Railroad.

Let us be honest, some people find lawn jockeys nostalgic, reminiscent of the "good old days" of Jim Crow segregation. The black-faced servant with the stooped back is a reminder of the decades when Blacks occupied the bottom rung on America's racial hierarchy -- a time when Blacks "knew their place." After World War II, White residents of new housing developments, "perhaps to give themselves more of a sense of being a member of the privileged master class, began placing 'Jocko' on their lawns in great numbers," wrote Kenneth W. Goings in his book Mammy and Uncle Mose. 5 I can tell you that more than a half-century later lawn jockeys are still seen by African Americans as markers of "White space," objects that send this message to Blacks: "You are not welcome here."

The early black-faced lawn ornaments were dressed in enslavement clothing (and called groomsmen), but at some point in the 1800s, these figures were joined and eventually superseded by the Jocko statues wearing the garb of horse riders. The dressing of black-faced ornaments as jockeys does not answer the question of their etymology, but it might give hints to their longtime popularity. Is it possible that black lawn jockeys became popular because of the preeminence of Blacks as horse racing jockeys? The enslaved were often used to train horses and, not surprisingly, some of the enslaved became skillful as horse riders. After all, why pay White riders in a slave economy? Horse racing was very popular in the 1800s. There were many races where all or most of the jockeys were African Americans. After Emancipation, Blacks continued to dominate major horse racing events. At the first race of the famed Kentucky Derby in 1875, 13 of the 15 riders were African Americans. Blacks rode the winners of 15 of the first 28 Kentucky Derby races. The dominance of Black jockeys ended just before World War I as Whites brought Jim Crow norms into horse racing. I am not arguing that black lawn jockeys came into existence because Blacks dominated professional horse racing, but I do believe that the popularity of the objects coincided with the dominance of Black jockeys. This fact was not lost on the makers, distributors, and buyers of lawn jockeys.

So, where does this leave us? There is no consensus on the jockey's origin. You can accept one of the legends (theories?) that I mentioned above, but the fact is that there is little evidence that supports these accounts. For years I have tried to find the name of the company that first received a patent for the lawn jockey, and I have sought to identify the first designer of the Jocko version -- in both searches I have failed. Of course, a greater aid to our understanding would be to find enslavement narratives that discuss the lawn jockeys. But no such narratives exist, to my knowledge (I hope that I am wrong). Thus, there is no consensus on the jockey's origin, but I do believe that there is a consensus view in African American communities that black lawn jockeys are demeaning relics of a racist past. They may not have started out with a racist meaning -- or always had that meaning -- but that is the meaning they have today. There are, undoubtedly, non-racist reasons for owning and displaying black lawn jockeys, but it would be hard for an adult American to claim that he or she does not know that many African Americans find lawn jockeys racially offensive, especially the ones with jet-black skin and oversized lips.

Moreover, to call an African American a lawn jockey is to insult him or her. When used by a Black person against another Black person, lawn jockey is synonymous with Uncle Tom, a derogatory term that has at least two distinct meanings. In the past it referred to the Black servant -- especially a cook, butler, or waiter -- who was perceived to be weak, ignorant, too religious, and humiliatingly deferential to white people. This definition was common before the civil rights movement. Today, Uncle Tom is an in-group pejorative that is used against Blacks whose views are considered selfish, conniving, too politically conservative, and detrimental to African Americans as a whole. In November 1996, Emerge, a liberal Black magazine, published an issue devoted, in large part, to criticizing Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. The magazine's cover showed a caricatured image of Justice Thomas as a lawn jockey accompanied by these words, "Uncle Thomas Lawn Jockey for the Far Right." Inside was a cartoon of a kneeling Thomas shining the shoes of fellow Justice Antonin Scalia. Black conservatives like Justice Thomas and Ward Connerly, the anti-affirmative action crusader, are often called Uncle Toms and Lawn Jockeys. When used by a White person against a Black person, lawn jockey is a racial slur somewhere between darky and nigger.

I have digressed into a truncated rant so I might as well make a few other points.

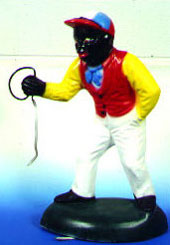

Lawn jockeys are often painted white or nearly-white today; this is especially true

of the non-caricatured "Cavalier spirit" version of the lawn decoration. Lawn jockeys

lost a lot of their popularity after the civil rights movement; however, it is apparent

that they are making a comeback. Google the words lawn jockey and you will find dozens of companies and hundreds of individuals selling old and

new versions of the statues. And they are not cheap. Your Internet search will also

reveal that lawn jockeys are sometimes sold to people in other countries. That probably

should not surprise us. There are also other black inanimate figures in yards, including

cement black-faced boys eating watermelons or fishing. And, finally, driving from

my home, I cannot go more than five minutes in any direction without seeing a waist

high, black lawn statue, dressed in jockey's clothing, holding one hand waiting for

the reins of a horse, with blood red lips, wild darting eyes, a large flat nose, and

a stooped back. And each time I see the black statues I think the following: the owners

have a right to put what they want in their yards; I wish they would donate the lawn

jockey to the Jim Crow Museum; and, finally, I think that I would be uncomfortable

in their yards or homes.

1 "The Story of Jocko," 23 May, 2008 http://www.mountainhomeplace.com/jocko.htm.

2 Anna Ditkoff, "Jockeying for Respect: With His New Children's Book, Waymon LeFall Wants to Change the Way People Think About Lawn Jockeys," CITYPAPERONLINE. 31 May, 2008 http://www.citypaper.com/arts/story.asp?id=5006

3 Earl Byrd, "Little Black Sambo," Afro-American Red Star, 29 November , 2002, Vol. 111, Iss. 15; pg. A7, accessed May 31, 2008 http://0proquest.umi.com.libcat.ferris.edu:80/pqdweb? did=490484741&sid=1&Fmt=3&clientId=52840&RQT=309&VName=PQD

4 Fredrick Kunkle, "In a Simple Lawn Ornaments, Echoes of Slavery, Revolution," Washington Post, September 17, 2006; Page A0, accessed 22 June, 2008 http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/09/16/AR2006091600851.html

5 "A Guide to Freedom: Jockey statue marked Underground Railroad," Lexington Herald-Leader, Sunday, February 22, 1998, accessed 21 June, 2008 Lexington Herald-Leader, http://www.horseinfo.com/info/misc/jockeyinfo.html

July 2008 response by David Pilgrim, Curator, Jim Crow Museum

Edited 2024