Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

As I'm sure you've heard many times before, your description of the children's book Little Black Sambo as racist is based on your misunderstanding of what the book is about. I read the book as a child, and even then realized that the characters were in India, not Africa. As has already been pointed out, there are no tigers in Africa, so the presence of tigers in the story must be an indication of the location of the story. Also, the mention of ghee in the conclusion of the story is another strong hint that the action takes place in India, since ghee is a staple ingredient in Indian cooking. The fact that the author lived in India for many years lends support to the notion that she set her story in India, not Africa. As you must know, the use of the word "black" to describe a person's physical characteristics has not always meant what it means today. The term "black" had a much broader range of meaning at the time the story was written, so in the story it is not referring specifically to people of African origin (and not all people of African origin are what is described today as "black"). It is misleading to include the book in your gallery of offenders in the Jim Crow Museum.

-- Paula Newman, England

Helen Bannerman's Little Black Sambo belongs in the Jim Crow Museum because her book served as the template for the many Little Black Sambo books, magazine stories, cartoons, toys, and musical records that ridiculed and mocked African Americans. Little Black Sambo is important in the history of American race relations, and a social scientist studying that history would be remiss to not trace the story to its origins; the story originated in the mind of Bannerman.

Bannerman's book was a fantasy with African and (mostly Indian) elements. While it is possible that Bannerman did not intend to pour scorn on Africans and Americans of African descent, there is little doubt that her book did portray indigenous dark-skinned Indians in a less than flattering light. This is especially true regarding the imagery in the book. The hero, Little Black Sambo, is drawn as a caricature. He has the appearance of a crudely drawn golliwog: very dark skin, wild curly hair, red lips, and bright and colorful clothing. He does not look like a little boy. The boy's mother, Black Mumbo, looks very similar to the Mammy caricature of Black women, and the father, Black Jumbo, looks like the caricature of American Blacks as Jim Dandy. They are all physically ugly. The fact that the story is set in India does not mean that Bannerman was not being racially insensitive; one need not be racist against African Americans to be racist. Stated differently, it can be argued that the book treated dark-skinned people of India as "Racially Strange Others."

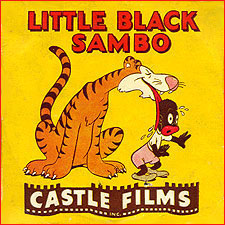

Bannerman's book belittled dark-skinned people from India and served as a boilerplate for people who wanted to mock African Americans -- one simply substituted Africans or African Americans in place of the "Indian" family. In 1899 the book appeared in England and was an immediate success. In 1900 it was published in the United States by Frederick A. Stokes, a mainstream publisher. It was even more successful than it had been in England. The book's success led to many imitators -- and overt anti-Blacks expressions. Barbara Bader, a book critic, summarized the events:

All American children did not see the same book, however. Though the authorized Stokes edition sold well and never went out of print, a host of other versions quickly began to appear from mass-market publishers, from reprint houses, from small, outlying firms unconstrained by the mutual courtesies of the major publishers. A few are straight knock-offs of the book that Bannerman made, without her name on the title page; the majority were re-illustrated -- with gross, degrading caricatures that set Sambo down on the old plantation or, with equal distortiveness, deposited him in Darkest Africa. Libraries stocked the Stokes edition, and a few others selectively. But overall the bootleg Sambos were much cheaper, more widely distributed, and vastly more numerous.1

Bannerman's version did not have characters using bastardized English or acting with stereotypical anti-Black traits, for example, laziness and stupidity; however the many versions of the story that came later often portrayed African Americans as ignorant, scared Mammies, Coons, and Pickanninies. This was also the case when the medium was cartoons. Little Black Sambo, a 1935 cartoon, includes four characters: Mammy, Sambo, a dog, and a tiger. The husband is conspicuously absent. The most intelligent character is the dog. Mammy speaks in racially stereotypical dialect, for example, she warns Sambo about the tiger: "That ol' tiger sho' do like dark meat!" The cartoon begins by playing on the stereotype of Blacks as physically dirty. Mammy scrubs the dirty boy in a washtub. When she finishes the water is as black as the ink-colored little boy. Mammy pats him with baby powder -- black baby powder. When Sambo meets the tiger he is so scared his skin temporarily turns white. This idea is often seen in jokes about scared Blacks. Here is an example of one way that the fear and loathing of Blacks is negotiated: make the Black skin disappear. Bannerman's Little Black Sambo character was a clever little boy who outwitted several tigers; the Sambo character in this cartoon is a scared little "pickaninny" who runs, yelps, and dances, but never speaks. See the cartoon: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jmG4SQeH7bo.

It is hard to know how aware Bannerman was of her racial views or the views that others had of Africans, African Americans, and other dark-skinned people. She was born Brodie Cowan Watson on February 25, 1862, in Edinburgh, the daughter of a Free Church of Scotland minister. She was educated privately. She married a surgeon, Will Bannerman, who was serving in the British Army of India, and spent thirty years of her life in India. She regularly wrote illustrated letters with fantasy storylines to entertain their children. In 1898 there "came into her head, evolved by the moving of a train," the entertaining story of a little Black boy, beautifully clothed, who outwits a succession of tigers, and not only saves his own life but gets a stack of tiger-striped pancakes. In 1898 she published the first and most famous of her books, The Story of Little Black Sambo, which she had written to amuse her two little girls. The word black did not have the same connotations that it would come to have -- it was more a descriptor than a slur; however, the Bannermans occupied a position of elitism that was based in part on the husband's occupational status and on their white skins in a nation of dark-skinned people. Helen Bannerman's books -- including, Story of Little Black Mingo (1901) and Story of Little Black Quibba (1902) and Little Black Quasha (1908) among others -- reflected a patronizing and sometime racially insensitive view of peoples of color.

At the time that the book was originally published Sambo was an established anti-Black epithet, a generic degrading reference. It symbolized the lazy, grinning, docile, childlike, good-for-little servant. Bannerman was an intelligent, well-read woman, but maybe she was unaware of the slur's connection with slavery and the emerging cultural practices that would support the Jim Crow racial hierarchy in the United States, South Africa, and other countries. Surely, she must have been aware of the role that skin color played for the British elite in India. In any event, her book fit neatly into the racial environment in the United States. What may have begun as an innocent attempt to write for and entertain her children led to one of the most racially divisive stories in United States history -- and that is part of Bannerman's legacy.

1 Barbara Bader, "Sambo, Babaji, and Sam," The Horn Book Magazine. September-October 1996, vol.72, no. 5, p. 536.

January 2008 response by

David Pilgrim

Curator

Jim Crow Museum