Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

I like what your museum does but I wonder if inadvertently you provide ammunition for censorship. There is a local group that wants to ban To Kill A Mockingbird and your museum is their "evidence."

-- Vernon Cairnie, New York, NY

The Jim Crow Museum does not advocate the banning of any books. Our goal is to use objects of intolerance to teach lessons of tolerance. Even books that are obviously racist, for example, Thomas Dixon's The Clansmen (1905), give us important insight into the racial attitudes and mores that once dominated this culture. Banning books stops conversations, and the goal of the Jim Crow Museum is to facilitate deep, even painful, discussions about race, race relations, racism, and racial healing.

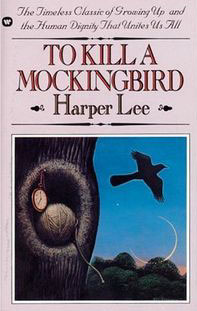

To Kill a Mockingbird is not only a literary masterpiece; it is a perceptive portrayal of the racial hierarchy that existed during the Jim Crow era. This semi-autobiographical novel, written by Harper Lee, is set in the Deep South in the 1930s. The protagonist and narrator of the story is Jean Louise Finch, nicknamed Scout. Her father, Atticus Finch, is an attorney appointed to defend a black man (Tom Robinson) falsely accused of raping a white girl.

To Kill a Mockingbird was inspired by the case of the Scottsboro Boys, where nine Black boys, ranging in age from 13 to 19, were falsely accused of sexually assaulting two White girls. The Scottsboro trials, in which the youths were sentenced to death by all-White juries despite the weak and contradictory testimonies of witnesses, represent the nadir of African American experiences with the United States criminal justice system. The death sentences, originally scheduled to be carried out quickly, were postponed and the cases eventually reached the United States Supreme Court, where the sentences were overturned. One of the women later denied being raped; nevertheless, the retrials resulted in convictions. All of the defendants were eventually acquitted, paroled, pardoned, or escaped, some after serving years in prison. The Scottsboro case sent this message to Black American men: regardless of the evidence, if a White woman said that you raped her you were guilty, and you would be lynched by a mob or legally lynched by a corrupt criminal justice system.

A Black man accused of raping a White woman in the 1930s was likely to be lynched. The lynching of Blacks was relatively common between Reconstruction and World War II. According to Tuskegee Institute data, between the years 1882 and 1951, 4,730 people were lynched in the United States: 3,437 Black and 1,293 White. Many of the White lynching victims were foreigners or belonged to oppressed groups, for example, Mormons, Shakers, and Catholics. By the early 1900s lynching had a decidedly racial character, that is, White mobs lynched Blacks. Almost 90 percent of all the lynchings of Blacks occurred in Southern or border states.

The lynching of Black men was seen as a necessary evil: a deterrent against the unforgivable crime -- the rape of a White woman. The accusation virtually guaranteed death to any Black male. If the accused managed to avoid being publicly tortured and killed he faced a hostile criminal justice system. The Black defendant faced White judges, all-White juries, and, in many cases, all-White audiences. The fate of the Black defendant rested in the hands of people who believed that White supremacy was natural, maybe divine. Typically, the local newspapers sensationalized the trials, and often advocated -- in language repulsive by contemporary standards -- the conviction and execution of the defendant.

Tom Robinson, the Black defendant, was a kind man who made the mistake of feeling sorry for Mayella Ewell. Her family was poor and marginalized -- stereotyped as "White trash." Her mother was dead. In a house of full of children she was the mother-substitute. Her father, Bob Ewell, was the town drunk -- and it is clear that he sometimes sexually abused his daughter. Tom helped Mayella by doing chores for her. He did not accept payment because he felt sorry for her. During the Jim Crow period Blacks were not allowed to feel sorry for Whites because that implied social equality, maybe social superiority.

Mayella asked Tom to chop a chest of drawers. He was a strong and a hard worker, even though his left arm was shriveled and useless. He had done her chores before. When he entered her home he discovered that both the children and Bob Ewell, her father, were gone. Mayella became sexually aggressive, but Tom resisted. He did not want to physically hurt her by pushing her away, but he knew what all Black men knew: that any Black man caught having sex -- or hugging, kissing or ogling -- with a White woman would likely be killed. She grabbed him about the waist, and as he pulled away he heard the yells of Bob Ewell. Tom ran. Later he was apprehended and charged with raping Mayella.

Surely, he had raped her; the town's Whites agreed. No Black man would do the chores of a White person gratis. Of course, he must have raped her. No White woman would say that a Black man had "defiled" her unless he actually did. And, she was supported by her father, Bob, "I seen that black nigger yonder ruttin' on my Mayella." Black Tom must have raped her, the white Ewells said he did, and if they lied and Black Tom was telling the truth, then nothing made sense.

Mayella testified that Tom raped her. Why? Because the prohibition against a White woman willingly having sex with a Black man was one of this country's most sacred mores. The idea that a White woman would sexually pursue a Black man contradicted the white supremacist notion that Blacks were inferior in all ways that mattered. White women were held up as paragons of virtue -- Black women were seen as asexual mammies or hypersexual tramps. Black men were portrayed as Toms, Sambos, and Coons -- all with the potential to become raping Brutes. White supremacists argued that White women had to be protected from "Black beasts" who desired nothing more than to defile the "purity of White womanhood." Mayella and the other Ewells were poor and disreputable, but they were White -- and Mayella's whiteness meant that all the town's Whites had to rally to her defense.

To Kill a Mockingbird accurately showed how racial identity was for most Whites a master status, meaning a status that trumps all others. By the time Atticus Finch had delivered his summary to the jury it was clear to any objective observer that Mayella and Bob Ewell were lying and that Tom Robinson was innocent. But the Whites could not set Tom free. It would have destroyed their racial identities and undermined the local racial hierarchy. Tom was guilty because he was Black. To Kill a Mockingbird showed the hypocrisy of the town's Christians, civil leaders, and teachers. It also showed how some individuals, in this case Atticus Finch, stood for justice even when it placed him and his family in danger.

No, the staff of the Jim Crow Museum does not advocate the banning of To Kill a Mockingbird. We recommend that it be read by every American. Books like To Kill a Mockingbird, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and Uncle Tom's Cabin are useful tools for deep discussions about race, race relations, and racism. Books like these should not be banned because they use the "N-word" or because they portray graphic depictions of racial bigotry. As Abraham Lincoln noted, "We cannot escape history," and these books are relatively accurate portrayals of sad periods in American history.

May 2007 response by

David Pilgrim

Curator

Jim Crow Museum