Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

A person looking at your Web site would get the impression that the Civil Rights Movement was a morality play where whites were the "bad guys" and Negroes were the "good guys." I am sure that you are aware that many whites were active in the Civil Rights Movement.

-- Jenni Burch, Grove City, Ohio

The Jim Crow Museum focuses on the anti-Blacks objects that were used to subordinate Africans and African Americans before, during, and after the Civil Rights Movement. We believe, and know to be true, that those objects functioned as propaganda -- reflecting and shaping attitudes towards Black Americans, and thereby legitimizing the Jim Crow racial hierarchy. The Civil Rights Movement may be viewed as "the beginning of the end" of official racial segregation; however, derogatory and hurtful caricatures and stereotypes of African Americans did not stop. Indeed, these negative portrayals of Blacks continue. This is not to say that the Civil Rights Movement did not move the United States in the direction of being a more democratic, egalitarian society. It did. The "morality play" involved many Americans -- and there were Whites on both sides.

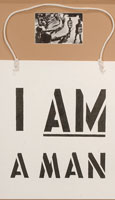

When the Jim Crow Museum moves into a larger facility, there will be a section on the Civil Rights Movement. We have collected hundreds of objects that might properly be called, "civil rights memorabilia." Think, for example, of a sign that reads, "I AM A MAN." That sign was commonly seen at civil rights demonstrations, including the 1963 March on Washington. Think, also, of the pen that President Johnson used to sign the 1964 Civil Rights Act, arguably the most comprehensive civil rights legislation in this country's history. Those are the types of objects that will be found in the new museum. There will be photographs and stories of the working class and poor people who risked their jobs and lives to march or boycott. There will be many individuals portrayed in these photographs -- most are African Americans but some are White Americans.

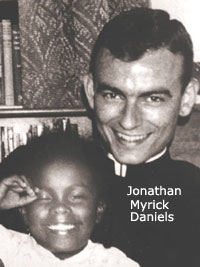

The last section of the new museum will house a mural with the likenesses of civil rights martyrs. The mural will be called, "Cloud of Witnesses." It will include Black, White, Brown, Red, and Yellow people who gave their lives during the Civil Rights Era. Not surprisingly, the mural will include some well-known names, for example, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Medgar Evers, but it will also include lesser known people, including, Jonathan Daniels -- a White American. Our respect for Daniels and his commitment to social justice is great. The remainder of this brief essay will introduce Jonathan Daniels to our viewers.

Jonathan Myrick Daniels was born in Keene, New Hampshire, March 20, 1939, the son of a doctor and school teacher. He graduated Valedictorian from Virginia Military Institute. In the fall of 1961 he entered Harvard University to study English literature. On Easter Sunday in 1962, while attending services at the Church of the Advent in Boston, he underwent a deep religious awakening. He decided to become a minister, left Harvard, and entered the Episcopal Theological School in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was drawn to the "Social Gospel" -- a socio-theological movement which applies Christian principles to social problems, especially poverty, inequality, racism, and war.

In 1965 Dr. Martin Luther King issued a nationwide call asking students and clergy of all faiths to come to Selma, Alabama to support the effort to gain voting rights for Blacks. That year, Daniels, then 26 years old, went to Selma and joined the voter registration drive. The young White seminarian was not naïve; he knew that helping Alabama's Blacks defy Jim Crow laws was dangerous but he was "living his faith." Daniels marched in the Selma to Montgomery protest demonstration and remained in the area to work with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Lowndes County. He lived with a Black family and quickly got the reputation -- among local African Americans -- as a Christian who would help Blacks gain the rights of first-class citizenship. "He had an abundance of strength that came from the inside that he could give to people," said Stokely Carmichael. "The people in Lowndes County realized that with the strength they got from Jon they had to carry on; they had to carry on!"

On August 13, 1965 Daniels and about two dozen other protestors were arrested for picketing "Whites-Only" stores in Fort Deposit, Alabama, and transferred to the county jail in nearby Hayneville. Five juvenile protestors were released after one day. The rest were held for six or seven days. The jail cells lacked air conditioning (the temperature regularly exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit), the food was overcooked, undercooked, or full of vermin. The cell was so crowded the protestors could not easily move. The toilet overflowed spilling sewage on the floor and a horrific stench in the air. On August 20, the protestors were released without transportation back to Fort Deposit.

Shortly after their release, Richard Morrisroe, a White Catholic priest, and Daniels accompanied two black teenagers, Joyce Bailey and Ruby Sales, to Varner's Grocery Store, one of the few stores in Haynesville that served Blacks. They wanted to buy sodas. They were met on the steps by Tom Coleman, an engineer for the Alabama Highway Department and unpaid special deputy, who was carrying a shotgun. Coleman threatened the group if they tried to enter the store. Coleman aimed his gun at 16-year old Ruby Sales; Daniels pushed her to the ground in order to protect her. A shotgun blast hit Daniels in the abdomen and killed him instantly. Morrisroe, the priest, grabbed Bailey and ran. Coleman shot Morrisroe in the back, seriously but not fatally wounding him.

When he heard of the tragedy, Martin Luther King, Jr. said, "One of the most heroic Christian deeds of which I have heard in my entire ministry was performed by Jonathan Daniels." Six weeks after the shooting, an all-white jury found Coleman not guilty of murder. In 1991, Jonathan Myrick Daniels was designated a martyr of the Episcopal Church, one of 15 modern-day martyrs, and August 14 was designated as a day of remembrance for the sacrifice of Daniels and all the martyrs of the Civil Rights Movement. Ruby Sales, whose life Daniels saved, attended Episcopal Theological School and founded an inner-city mission dedicated to Daniels. Dr. King handed a baton to Daniels who handed one to Sales.

June 2007 response by

David Pilgrim

Curator

Jim Crow Museum