Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

No race-loving White person would ever marry a negro. We should go back to the old laws.

-- Corine J., Wisconsin

You are right: a White supremacist should probably not marry an African American.

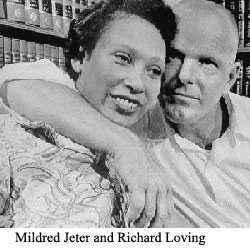

The old laws that you referenced were finally overturned on June 12, 1967, when the United States Supreme Court in the case of Loving v. Virginia, reversed the laws that forbade interracial marriages. Mildred Jeter, a Black woman, and Richard Loving, a White man, committed a felony under Virginia law because, after marrying in the District of Columbia, they lived together as husband and wife in Caroline County, Virginia. Doing so violated the state's antimiscegenation (interracial marriage) law, which prohibited any white person ... to marry any save a[nother] white person." A Virginia judge sentenced both husband and wife to a year in prison, suspended on the condition that they leave Virginia and not return for twenty-five years. The judge also lectured them on the significance and justifiability of the state's Racial Integrity Act, arguing that "Almighty God" placed the races on different continents because He "did not intend for the races to mix." The Judge's comments were typical. A 1965 Gallup Poll indicated that 42 percent of Northern Whites supported bans on interracial marriage, as did 72 percent of southern Whites.

At the time of the Loving decision interracial marriages were legally banned in sixteen states -- many other states had enacted such laws in previous years but had repealed them by the time of Loving -- and all fifty states had communities where interracial couples faced ostracism and violence.

The fear of interracial marriage was a major argument used to support racial segregation during the Jim Crow Era. Segregationists claimed that "social equality" would lead to interracial sexual unions between Black men and White women -- of course, White men had sexual access to Black women from slavery through the 1960s. The segregationists claimed that Whites were superior to Blacks and other races in every important way -- culturally, socially, intellectually, physically, and morally. Blacks were seen as a third-rate race whose inferiority was immutably stamped by God or nature. The intermingling of the races would lead to disaster: White women, it was argued, would produce inferior mongrel children -- with the ambition and desire of Whites but the animal-like qualities of Blacks. Beaches, parks, movie theaters, hospitals, schools and other "public spaces" had to be segregated by race to prevent interracial unions -- sexual and non-sexual. It is difficult for contemporary Americans to understand the antipathy felt by many Whites toward Blacks during the Jim Crow Era, and to understand the fear of miscegenation that existed at the time of the Loving decision. As your email demonstrates the residue of that fear remains.

It may be profitable for our readers to read the abridged text of the Loving decision. The full text is easily accessible via the Internet.

RICHARD PERRY LOVING et ux., Appellants,

v.

VIRGINIA

388 US 1, 18 L ed 2d 1010, 87 S Ct 1817

Argued April 10, 1967. Decided June 12, 1967.

The issue presented in the instant case concerned the validity of the Virginia antimiscegenation statutes, the central features of which are the absolute prohibition of a "white person" marrying any person other than a "white person."

A husband, "a white person", and his wife, a "colored person," within the meanings given those terms by a Virginia statute, both residents of Virginia, were married in the District of Columbia pursuant to its laws, and shortly thereafter returned to Virginia, where, upon their plea of guilty, they were sentenced, in a Virginia state court, to one year in jail for violating Virginia's ban on interracial marriages. Their motion to vacate the sentences on the ground of the unconstitutionality of these statutes was denied by the trial court. The Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals affirmed. (206 Va 924, 147 SE2d 78)

On appeal, the Supreme Court of the United States reversed the conviction. In an opinion by WARREN, Ch.J., expressing the view of eight members of the court, it was held that the Virginia statutes violated both the equal protection and the due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

STEWART, J., concurred in the judgment on the ground that a state law making the criminality of an act depend upon the race of the actor is invalid.

Phillip J. Hirschkop argued the cause for appellants, pro hac vice, by special leave of Court.

Bernard S. Cohen argued the cause for appellants.

R.D. McIlwaine argued the cause for appellees.

William M. Marutani argued the cause for the Japanese American Citizens League, amicus curiae, by special leave of Court.

Mr. Chief Justice Warren delivered the opinion of the Court.

This case presents a constitutional question never addressed by this Court: whether a statutory scheme adopted by the State of Virginia to prevent marriages between persons solely on the basis of racial classifications violates the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. For reasons which seem to us to reflect the central meaning of those constitutional commands, we conclude that these statutes cannot stand consistently with the Fourteenth Amendment.

In June 1958, two residents of Virginia, Mildred Jeter, a Negro woman, and Richard Loving, a white man, were married in the District of Columbia pursuant to its laws. Shortly after their marriage, the Lovings returned to Virginia and established their marital abode in Caroline County. At the October Term, 1958, the Circuit Court of Caroline County, a grand jury issued an indictment charging the Lovings with violating Virginia's ban on interracial marriages. On January 6, 1959, the Lovings pleaded guilty to the charge and were sentenced to one year in jail; however, the trial judge suspended the sentence for a period of 25 years on the condition that the Lovings leave the State and not return to Virginia together for 25 years. He stated in an opinion that:

"Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix."

After their convictions, the Lovings took up residence in the District of Columbia. On November 6, 1963, they filed a motion in the state trial court to vacate the judgment and set aside the sentence on the ground that the statutes which they had violated were repugnant to the Fourteenth Amendment. The motion not having been decided by October 28, 1964, the Lovings instituted a class action in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia requesting that a three-judge court be convened to declare the Virginia antimiscegenation statutes unconstitutional and to enjoin state officials from enforcing their convictions. On January 22, 1965, the state trial judge denied the motion to vacate the sentences, and the Lovings perfected an appeal to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia. On February 11, 1965, the three-judge District Court continued the case to allow the Lovings to present their constitutional claims to the highest state court.

The Supreme Court of Appeals upheld the constitutionality of the antimiscegenation statutes and, after modifying the sentence, affirmed the convictions. The Lovings appealed this decision, and we noted probable jurisdiction on December 12, 1966.

The two statutes under which appellants were convicted and sentenced are part of a comprehensive statutory scheme aimed at prohibiting and punishing interracial marriages. The Lovings were convicted of violating Section 20-58 of the Virginia Code:

"Leaving State to evade law. -- If any white person and colored person shall go out of this State, for the purpose of being married, and with the intention of returning, and be married out of it, and afterwards return and reside in it, cohabiting as man and wife, they shall be punished as provided in Section 20-59, and the marriage shall be governed by the same law as if it had been solemnized in this State. The fact of their cohabitation here as man and wife shall be evidence of their marriage."

Section 20-59, which defines the penalty for miscegenation, provides:

"Punishment for marriage. -- If any white person intermarry with a colored person, or any colored person intermarry with a white person, he shall be guilty of a felony and shall be punished by confinement in the penitentiary for not less than one nor more than five years."

Other central provisions in the Virginia statutory scheme are Section 20-57, which automatically voids all marriages between "a white person and a colored person" without any judicial proceeding, and Sections 20-54 and 1-14 which, respectively, define "white persons" and "colored persons and Indians" for purposes of the statutory prohibitions. The Lovings have never disputed in the course of this litigation that Mrs. Loving is a "colored person" or that Mr. Loving is a "white person" within the meanings given those terms by the Virginia statutes.

Virginia is now one of 16 States which prohibit and punish marriages on the basis of racial classifications. Penalties for miscegenation arose as an incident to slavery and have been common in Virginia since the colonial period. The present statutory scheme dates from the adoption of the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, passed during the period of extreme nativism which followed the end of the First World War. The central features of this Act, and current Virginia law, are the absolute prohibition of a "white person" marrying other than another "white person", a prohibition against issuing marriage licenses until the issuing official is satisfied that the applicants' statements as to their race are correct, certificates of "racial composition" to be kept by both local and state registrars, and the carrying forward of earlier prohibitions against racial intermarriage.

In upholding the constitutionality of these provisions in the decision below, the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia referred to its 1955 decision in Naim v. Naim as stating the reasons supporting the validity of these laws. In Naim, the state court concluded that the State's legitimate purposes were "to preserve the racial integrity of its citizens", and "the obliteration of racial pride," obviously an endorsement of the doctrine of White Supremacy. The Court also reasoned that marriage has traditionally been subject to state regulation without federal intervention, and, consequently, the regulation of marriage should be left to exclusive state control by the Tenth Amendment.

While the state court is no doubt correct in asserting that marriage is a social relation subject to the State's police power, the State does not contend in its argument before this Court that its powers to regulate marriage are unlimited, notwithstanding the Fourteenth Amendment. Nor could it do so in light of Meyer v. Nebraska (1923) and Skinner v. Oklahoma (1942). Instead, the State argues that the meaning of the Equal Protection Clause, as illuminated by the statements of the Framers, is only that state penal laws containing an interracial element as part of the definition of the offense must apply equally to whites and Negroes in the sense that members of each race are punished to the same degree.

The clear and central purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment was to eliminate all official sources of invidious racial discrimination in the States. There can be no question but that Virginia's miscegenation statutes rest solely upon distinctions drawn according to race. The statutes proscribe generally accepted conduct if engaged in by members of different races. At the very least, the Equal Protection Clause demands that racial classifications, especially suspect in criminal statutes, be subjected to the "most rigid scrutiny", and, if they are ever to be upheld, they must be shown to be necessary to the accomplishment of some permissible state objective, independent of the racial discrimination which was the object of the Fourteenth Amendment to eliminate. Indeed, two members of this Court have already stated that they "cannot conceive of a valid legislative purpose...which makes the color of a person's skin the test of whether his conduct is a criminal offense."

There is patently no legitimate overriding purpose independent of invidious racial discrimination which justifies this classification. The fact that Virginia prohibits only interracial marriages involving white persons demonstrates that the racial classifications must stand on their own justification, as measures designed to maintain White Supremacy. We have consistently denied the constitutionality of measures which restrict the rights of citizens on account of race. There can be no doubt that restricting the freedom to marry solely because of racial classifications violates the central meaning of the Equal Protection Clause.

These statutes also deprive the Lovings of liberty without due process of law in violation of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The freedom to marry has long been recognized as one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.

Marriage is one of the "basic civil rights of man," fundamental to our very existence and survival. To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State's citizens of liberty without due process of law. The Fourteenth Amendment requires that the freedom of choice to marry not be restricted by invidious racial discriminations. Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual and cannot be infringed by the State.

These convictions must be reversed.

It is so ordered.

February 2006 response by

David Pilgrim

Curator

Jim Crow Museum