Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

If you watch UPN the programming is very stereotypical with old demeaning images of African Americans reborn and morphed into the present. Amos 'N' Andy has been reborn. Do you think television programming is repeating the mistakes of the past?

-- Shannon Greenbay, La Jolla, California

Amos 'n' Andy was born on radio in 1928. But its stereotypes and caricatures have roots deep in American culture and branches that are still evident today. The negative images in Amos 'n' Andy not only have historical precedents, but that they continued to inform televised representations of black Americans long after the show was no longer available.

What is the significance of these depictions in popular culture on the African-American family? African Americans are among the heaviest viewers of commercial television. As a working premise it may be fair to assume that images are not insubstantial, that they powerfully shape perceptions, values and behavior; and that consequently negative images have negative consequences. The negative consequences of television viewing are likely to be disproportionally borne by viewers who are younger, less educated, and those whose sense of self-worth and self-image are the least formed -- that is our children. In particular, the unmonitored, unsupervised, uncritical viewing of television puts children at risk, and makes them the most vulnerable to negative consequences. I've chosen Amos 'n' Andy for this case study because of the importance of the show -- both as a radio series and as the first national television series to cast African-Americans in leading roles. Because the last Amos 'n' Andy radio program was broadcast on 1/25/60, and the television series was withdrawn from syndication in 1965 a generation and a half has grown up without direct access to the material.

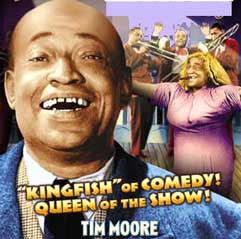

Between June 28, 1951 and June 11, 1953 CBS broadcast 78 half hour episodes. The programs were shot on black and white film, and in 1951 the series was the most expensive show produced for television. The program was designed as a situation comedy set in Harlem. The majority of the stories revolved around the Kingfish (Tim Moore) and his schemes to both avoid work and, if possible, take financial advantage of the ignorance and naiveté of Andy and other characters/caricatures. Although set in a decidedly middle class milieu and often depicting black professionals, the series did little to support black self-esteem, needless to say it did provide positive role models.

Amos 'n' Andy was created by Charles Correll and Freeman Godsen. Their personal histories were shaped by the Civil War and the legacy of slavery and race relations in the South. Correl's family was related to Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy. Godsen's father joined the rebels at 17 and was one of 75 officers who refused to surrender at Appomattox. Godsen claimed to have been raised by a "mammy" and shared his home with Garrett Brown, an African-American boy "adopted" by the Godsens.

Freeman and Garrett created minstrel shows for the family's entertainment. In fact the minstrel show tradition is the foundation for the "humor" of Amos 'n' Andy which depends on race for its effect. What are the characteristics common to these popular entertainments? Perhaps the most salient feature is that both Amos 'n' Andy and minstrel shows were created by whites, to entertain primarily white audiences. Thomas Rice created the Jim Crow caricature -- "plantation style" song and dance combined with "comic" dialect. By the 1850s minstrel shows were popular throughout the United States and toured widely in Europe. By the 1920s these caricatures had become institutionalized in American popular culture. In fact the first talking picture The Jazz Singer (1927) starred Al Jolson singing "Mammy" in black face. Books of "Darky Jokes," "Minstrel Jokes," and "Coon Jokes" were readily available in most 5 and 10 cent stores.

On the Real Side by Mel Watkins (pp. 29-32) raises issues critical to an understanding humor at the expense of blacks and "Black Humor." "Blacks were funny for most white Americans only insofar as they engaged in quaint, foolish or childlike behavior, or stumbled over a language they were only half heartily taught to speak, and [during slavery] forbidden to read." (Watkins, p. 29). This "naive humor" reinforces the power relationships between superior whites and inferior childlike blacks. Nathan Huggins' Harlem Renaissance in (Lipsitz in Spigel and Mann) "points out that minstrel show stereotypes enabled white society .... to attribute to black people the characteristics that it feared the most in itself ...." Blacks represent laziness, greed, gluttony and licentiousness. The "... psychic reinforcement... enabled whites to accept the suppression of their natural selves" (Lipsitz 94), and instead embraced thrift, sobriety, abstinence and restraint -- behaviors necessary to the functioning of an industrial capitalist order. ... "Amos 'n' Andy did for the values of the 1950s what the minstrel shows accomplished for previous generations.

Everything considered precious but contested in white society -- like the family or the work ethic -- became violated in the world of the Kingfish (Lipsitz, 95).

When the same type of humor is employed by blacks for blacks it has been describes in psychological parlance as "masochism" -- redirecting rage away from dangerous persecutors and onto themselves. This is a kind of false consciousness; an internalized oppression, a self-hating notion that agrees with the stereotypes. This is a tendency not unique to African Americans. Freud described the phenomenon in his discussions of Jewish humor. This strategy may appease whites, at the expense of further eroding estimates of black self-worth.

On the other hand, when such jokes are delivered by blacks for black audiences there is an undeniable sense of irony -- intended to reveal the barbarity of a system premised on a system of inherent inferiority. Activist Julius Lester reversed the messages of Amos 'n' Andy. "Kingfish has a joie de vivre no white person could poison, and we knew that whites ridiculed us because they were incapable of such elan. I was proud to belong to the same race as Kingsish" (in Lipsitz 97). So how should we understand the humor in Amos 'n' Andy? Henry Louis Gates recounts that "One of my favorite pastimes is screening episodes of Amos 'n' Andy for black friends who think that the series was both socially offensive and politically detrimental." ... He assets that, "The performance of those great black actors ... transformed racist stereotypes into authentic black humor." The historian Thomas Cripps suggests that only the main characters are stereotyped by language and dress. He points to many examples of well-dressed, supporting actors speaking in Yankee accents. (In fact there were Black professionals including a doctor, a minister, a teacher, a detective, a real estate broker and a nurse.) Only a few of these professionals were darker skinned. My own reading is that this does little to mitigate the show's concentration on and viewers repeated exposure to the negative impressions created by the lead characters.

Context has much to do with our evaluations. Patricia Davis a UC professor, "I think how excited my relatives would be when blacks first showed up on tv -- it didn't matter that it was Amos 'n' Andy. It was just a confirmation that there were blacks in the world" (LA Times). Similarly Gates recalls his mother shouting that "someone 'colored ... colored!' was on TV and we had all better come downstairs at once" (Gates, NYT).

Today images of oppression are sometimes reclaimed by reframing them. Lightning's molasses like slowness in Amos 'n' Andy can be read as subversive. He's dragging his feet not obeying. In analyzing the effects of comedy I believe it's essential to determine whether the humor is subversive -- a challenge to authority and conventional wisdom; or mainly cathartic -- temporarily releasing (social) tension, but ultimately supporting the status quo. Perhaps one key to use is to determine who's doing the laughing -- and at whose expense." ... Hollywood's slickest hipster[s] operate not as cultural purveyors of black American life, but rather as safety valves, generating laughs that mask the conflict between black aspirations and the maintenance of white power" (Erhenstein, 9).

In the minstrel shows and their successors on radio, white men impersonated black men. (In fact a white man -- Marlin Hurt -- even played a black woman -- Beulah, a character instantly recognizable by her high-pitched screams.) Lillian Rudolph who played Madame Queen, Andy's girlfriend on the tv series, spent three months studying with a white vocal coach so that she could master the "minstrel style black dialects" (A&J p., 35). And Godsen himself coached the black male actors. He maintained that as the creator of the series he "ought to know how Amos and Andy should talk." Spencer Williams -- Andy in the TV series -- had been an director of independent black films. He replied to Godsen that I "ought to know how Negroes talk, having been one all my life" (Clayton, Ebony in Fife p. 9). What we have is "a white man teaching a negro how to act like a white man acting like a negro" (A&J p., 35). Take away this phony accent and much -- if not all -- of the "humor" is drained from the dialog. Minstrel shows reached thousands and created the framework for popular depictions of black life. Radio and later television uncritically adopted these portrayals and by the agency of the mass media shaped our shared culture. The Amos 'n' Andy radio show at its height was a pervasive artifact of American culture. In 1931 there were an estimated 40 million nightly listeners out of a U.S. population of 123 million. At times the show captured 74 percent of the national radio audience (A&J p., 31). The program was mentioned frequently in the Congressional Record. 2.4 million fans wrote in suggesting names for Amos' and Ruby's newborn daughter. The show introduced a number of expressions into the vernacular including: "Check and Double Check; Holy Mackeral," and "I'se regusted." [Not to mention the characters of the series themselves. For example Huey P. Long the populist governor of Louisiana ironically took his nickname "The Kingfish" from the series]. And the show's popularity resulted in a variety of lucrative spin-offs including a daily comic strip, a candy bar, toys, greeting cards, two books and a feature film. The prospect of an Amos 'n' Andy TV show was eagerly anticipated. Experimental TV broadcasts were made throughout the 1930s and in fact one broadcast at the 1939 New York World's Fair featured Godsen and Correll as Amos 'n Andy.

What were the basic caricatures common to the minstrel tradition and Amos 'n' Andy? Fred MacDonald, radio historian (Don't Touch That Dial) describes three such characterizations. (Note Gates, NYT 11-12-89 -- "In 1933, Sterling Brown, the great black poet and critic divided the full range of black character types in American literature into seven categories: the contended slave; the wretched freeman; the comic Negro; the brute Negro; the local color Negro, and the exotic primitive.")

Coons -- a clown, murdering the English language, conniving to fleece a comrade out of money, bumblingly avoiding employment -- The Kingfish -- stupid and scheming, and Andy lazy and domineering. "Consistent with the values of the 1950s as mediated through popular culture, family responsibilities -- or neglect of them -- define Kingfish ... his most serious flaws stem from his neglect of the proper role of husband and father" (Lipsitz 95-96). "As in so much of American comedy, marriage in Amos 'n' Andy gave us a snare and a straitjacket -- a cruel prank played upon men who'd rather be fishing, swapping lies, wiping beery foam from their lips in a cool, dark bar. Instead they find that married life is one long chore; the honey-tempered angels they wooed in innocent youth have turned into witches, shrews. ... When Andy announces his engagement to a 21-year-old beauty queen, the Kingfish slaps him on the shoulders and chortles, "Welcome to the land of the living dead" (Wolcott in A&J p. xviii).

Lightning was a Step'n Fetchit-like character. He was dull witted and slow of speech. He moved like "molasses" (not lightning). He played one of the most demeaning roles -- but was not without self-awareness. Nick Stewart says he took the role because "I couldn't have learned without an opportunity to play these roles, but I saw how this was poisoning the black community. People used to say to my children -- "Hey let me see you talk like your daddy."

Calhoun the "shyster." This portrayal of a "coon lawyer" was perhaps one of the most offensive to middle class African Americans. The NAACP complained bitterly about the portrayal of "Negro lawyers ... as slippery cowards, ignorant of their profession and without ethics" (A&J p. 62).

Toms are typically good, gentle, religious and sober. In their 1929 book, All About Amos 'n Andy, Correll and Godsen described Amos as -- "trusting, simple, unsophisticated" (p. 16). This is an example of the notion that we're all equal before God and saved by faith and prayer. A romantic if not outright reactionary response to the realities of racism (segregation, poverty, lack of educational opportunities) which existed outside the boundaries of the show.

Mammy is quick tempered, a source of earthy wisdom who brooks no backtalk. Kingfish's wife Sapphire, and especially her mother, are frequently cast as the Kingfish's foils. The result is domestic violence -- usually verbal, sometimes physical. "The glorification of motherhood pervading psychology and popular literature of the the 1950's becomes comedy in Amos 'n' Andy. Wives named for precious stones (Ruby and Sapphire) are anything but precious, and "Mama" in this show appears as a nagging harpy screaming at the cowering -- and emasculated -- black man." (Lipsitz 95 The Meaning of Memory: Family, Class and Ethnicity in Early Network Television Programs.)

What was the response of the African-American community to Amos 'n Andy? Thomas Cripps identified three types of reactions by activists in the period between World War I and World War II -- like the NAACP attempted to affect the products of white producers. They often called for substantial changes to offending programs. This response was often characterized as censorship. The second response was of "Hollywood Negroes" who in defense of their limited livelihoods were often opposed to the activists. The alternatives as they perceived them were that they could either play a maid for $700 a week or be a maid for $7 a week. The third kind of response came from independent producers of "race movies" who were often far removed from the Hollywood sources of expertise, funds and distribution. Seizing the "means of production" they produced hundreds of all black films between 1914 and 1950. These pictures were inspired by a backlash against racist depictions of black life. In 1937 there were about 800 inner city theaters -- most of which featured all black films. Most of these films were Black imitations of Hollywood B genre films -- black cowboys, cops and crooks. Even the most obvious genre picture had the advantage of depicting blacks as people rather than social problems. Perhaps the most well-known producer of "race movies" was Oscar Micheaux who wrote, produced, directed and distributed over 20 films between 1918 and 1940.

There is evidence of some support for the program among certain segments of the black community. For example, in 1931 Chicago's weekly black newspaper the Defender invited Godsen and Correll to be guests of honor at a community picnic which the Defender described as being attended by 35,000 (and Time magazine characterized as 6000 pickaninies). Duke Ellington's Cotton Club band played "The Perfect Song." The audience broke into applause identifying it as the theme song of Amos 'n' Andy rather than from the 1915 Ku Klux Klan epic Birth of a Nation (Ely 4). At about the same time the Pittsburgh Courier was editorializing for the banning of the program from the airwaves. (Ironically by the time of the TV series the Courier would be calling the NAACP protesters of the series "pinks.")

A survey of Negro "adult leaders" in 1932 confirmed the division of opinion about Amos 'n' Andy which ranged from sheer delight to "marked resentment and emphatic disapproval" (Cripps p. 267).

The imminent arrival of TV in America was predicated since the 1920s. Experimental broadcasts were made in the 1930s including one at the 1930 New York World's Fair which featured the radio stars from Amos 'n' Andy. Television didn't really take off in the U.S. until the 1950s. Amos 'n' Andy was sponsored by Blatz Beer and ran from 6/28/1951 to 1953.

When the show premiered it was the only one with an all black cast. (Although the writers, directors, producers, and technicians were white.) In fact, the program was designed for white audiences. Especially in the early 1950s TV audiences were restricted to those who could afford the new appliances -- about 20 million predominately white households.

The TV shore framed itself as folklore explicitly comparing the show to Huck Finn, Paul Bunyan and Rip Van Winkle (A&J 1). Perhaps Uncle Remus might have been a better comparison.

In response to NAACP protests about the TV show, a survey by Advertest (sponsored by the network) claimed that 75 percent of the 365 blacks interviewed disagreed with the proposition that Amos 'n' Andy reinforced stereotypes. The program's premier coincided with the NAACP's 1951 Congress and was viewed by the delegates assembled. Organizing received a head start from this circumstance. This is how the NAACP characterized it's objections to the show:

Why was the NAACP eventually more successful in mounting a campaign against the TV show than the radio show? Before World Ware II the NAACP had been a shadow of its postwar size and strength. But "membership increased 10 times over during the 1940s. By 1948 black leaders were making waves in American journalism and entertainment. The Democratic Party courted them in the election. President Truman appointed a Civil Rights Commission and declared 1949 a 'Year of Rededication' to the principals of racial equality ... The liberal concept of full integration -- gradual, painless, nonviolent, but inevitable, captured the American conscience" (Jones 51).

The times had changed. The same Defender picnic that feted the white Godsen and Correl in 1931 denied the all-black cast an invitation 20 years later in 1951. In 1951 the show ranked 13th in the Nielsen ratings (A&J 62). And in 1952 it won an Emmy award.

The NAACP responded by initiating a boycott of Blatz beer. By April 1953 Blatz withdrew its sponsorship and CBS announced "The network has bowed to the change in national thinking." Yet the series was in syndication more than four times as long as it was broadcast on the network. It remained in syndication for 13 years after it was withdrawn from the network schedule. And it aired in 218 markets in the U.S. as well as in Australia, Bermuda, Kenya and Western Nigeria. As late as 1963 it still played on 50 U.S. stations. The programs were finally locked in vaults as of 1966. Yet in the 1970s CBS applied for a renewal of its copyright. Networks reacted to the controversy over Amos 'n' Andy by eliminating black families from television. Fifteen years passed from Amos 'n 'Andy until the introduction of another African-American situation comedy (Julia in 1968). I would argue that despite the legacy of the civil rights movements, and the rise of a substantially larger African-American middle class, the stereotypes of Amos 'n' Andy have been recycled from year to year and show to show. The 1970s continued to feature "coons and mammies" in minstrel shows including Sanford and Son, The Jeffersons, Good Times, What's Happening, and Diff'rent Strokes (Cummings, 78: The Changing Nature of the Black Family).

Even The Cosby Show, while seeming to be the exception to this trend, may have reinforced preconceptions among white viewers through its ironic portrait of successful black professionals. For both Amos 'n' Andy and Cosby live in world which seems determined only by personal choice. Cliff Huxtable's affluence and the Kingfish's chronic unemployment are not placed in a social context. Racism, discrimination, the historical roots of poverty and lack of opportunity are nowhere to be found in these shows. Cosby and the Kingfish both move in a world without social constraints, where individual initiative or its lack are the only determinants. "The domestic bliss of the Huxtable household is perceived by whites as the exception to the rule of black family life, reaffirming the notion that racism wouldn't be a problem if only blacks were more like 'us'" (Ehrenstein, The Color of Laughter p. 8). Both Amos 'n' Andy and the Cosby Show reinforce a singular vision of the American Dream. The close identification of Bill Cosby and Clift Huxtable confirms the "truth" of American fairness and opportunity (Jhally and Lewis p. 8 and Miller pp. 213-214 in J & L).

Negative stereotypes of black life continue. South Central was, in the words of Brotherhood Crusade President Danny Blackwell, "the Amos 'n' Andy of 1994." Ultimately as Tony Brown has observed, black families "became narrow, negative, stereotypical portrayals designed to reflect what television producers and distributors believe the majority of the American public/market imagines black families to be." (Television and the Black Family in Black Families and the Medium of Television, p. 85, see note Cummings images of the black family.)

Are there solutions to the problems I've identified here? Historically there has been a call for greater black participation in all phase of television. If there were more black producers, if there were more black writers -- goes the argument -- if there were more black actors and more black television programs, then African-American images would be represented more accurately. Unfortunately, the evidence does not seem to support such an outcome. Fox TV more than any other network "has been committed to airing so-called black programs in prime time ... nearly a third of Fox's series [in 1994] were black oriented....." (Rosenberg p. F32). And yet not a single on-going program represents a substantial improvement in the depiction of African-American families. A poignant example -- Robert Townsend, a well-respected, talented African-American actor and independent filmmaker, is the star and co-executive producer of Parent in the 'Hood. The program -- theoretically aimed at family viewers, is crude, sexually explicit and tasteless, and relies on working class coon and mammy caricatures for a good portion of its "humor." The easy answer to why these forms persist lies in the exigencies of a market-driven, consumerist commercial television industry. "The sitcom is a corporate product. It is a mass consumption commodity ... The promises of bureaucratic democracy, managerial capitalism, secular humanism, and mass consumption are miniaturized, tested, and found true in the funny travails of TV families. The sitcom is the Miracle play of consumer society" (Jones p. 4).

Perhaps the coming 500 channel universe will offer diversity, intelligence and humor not based on racist stereotyping. Or perhaps we will have 500 channels of the same old ... same old. Let me suggest that while it is essential to continue to organize and protest the debasing impacts of negative television images, it is simultaneously imperative that we empower our children to become critical viewers. Unless we teach ourselves and our children the basic skills of media literacy, there is too great a risk that we will become what we watch. The alternative is to choose television selectively, to watch it actively, to discuss and analyze the programming with children, to take control of an electronic medium that comes into our most intimate environment.

Children ought to be engaged as producers of video, not as passive consumers. Making video is one of the best ways to understand the mechanisms of television. Given access to tools and encouragement to create images that correspond to the realities of their lives, a new generation may be able to create community-based productions that capture the reality of their families and their experiences. Perhaps the future offers the possibility of a decentralized, democratized media -- a model not unlike the Internet which offers many voices for each of us to choose; rather than as mass media from a few centralized sources to the largest possible audience.

What ever the future holds, it is clear that the popular models of African-American family found on television are need in of radical change.

Andrew, Bart, and Ahrgus Juilliard, Holy Mackeral! The 'Amos 'n' Andy Story, New York: E.P. Dutton.

Bogle, Donald, Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, & Bucks, NewYork: Bantam Books, 1974.

Boskin, Joseph, "The Rise and Demise of an American Jester", Sambo, New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Correll, Charles J., and Freeman J. Gosden, All About 'Amos 'n' Andy' and Their Creators Correll and Gosden, New York: Rand McNally & Company, 1929.

Cripps, Thomas Robert, Slow Fade to Black: The Negro in American Film, New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Cripps, Thomas Robert, "'Amos 'n' Andy' and the Debate Over American Racial Integration" in O'Connor, John, ed., American History American Television, New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1983.

Cummings, Melbourne S., "The Changing Image of the Black Family On Television", Journal of Popular Culture, (Fall 1988): 75-85.

Ellison, Mary, "The Manipulating Eye: Black Images in Non-Documentary T.V", Journal of Popular Culture, (Spring 1985): 73-79.

Ely, Patrick, "The Adventure of Amos 'n' Andy: A Social History for American Phenomenon", The Free Press, 1991.

Fife, Marilyn Diane, "Black Image in American TV: The First Two Decades", Black Scholar, 6, (1974): 7-15.

Fuller, Linda K., The Cosby Show: Audiences, Impact, and Implications, Westport: Greenwood Press, 1992.

Gates, Henry Louis, "The World Turns, But Stays Unreal", New York Times, (November 12, 1989): H1.

Giddings, Paula, When and Where I Enter, The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America, New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1984.

Jhally, Sut, and Justin Lewis, Enlightened Racism: "The Cosby Show", Audiences, and the Myth of the American Dream, Boulder: Westview Press, 1992.

Jackson, Anthony, ed., Black Families and the Medium of Television, Michigan: University of Michigan.

Jones, Gerard, Honey, I'm Home!, New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1992.

Kagan, Norman, "'Amos 'n' Andy': Twenty Years Late, or Two Decades Early?", Journal of Popular Culture 6, (Summer 1972): 71-75.

Lipsitz, George. "The Meaning of Memory: Family, Class and Ethnicity in Early Network Television Programs" in Spiegel, Lynn and Denise Mann eds., Private Screenings: Television and the Female Consumer, 1992 Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Correll and Godsen, 1929, All About Amos 'n Andy.

MacDonald, J. Fred, Don't Touch That Dial! Radio Programming in American Life, 1920-1960, Chicago: Nelson-Hall Publishers.

MacDonald, J. Fred, Blacks and White TV: Afro-Americans in Television since 1948, Chicago: Nelson-Hall Publishers.

Reid, Mark A., Redefining Black Film, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Shankman, Arnold, "Black Pride and Protest: The 'Amos 'n' Andy' Crusade", Journal of Popular Culture (Fall 1978): 236-252.

Staples, Robert, and Leanor Boulin Johnson, Black Families at the Crossroads, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1993.

Watkins, Mel, On the Real Side, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994.

Woll, Allen L, and Randal M. Miller, Ethnic and Racial Images in American Film and Television, New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1987.

October 2005 response by

Mark Freeman, Associate Professor

School of Theatre, Television and Film

San Diego State University