Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

What were coon songs? Did they have something to do with minstrel shows?

-- Kelli Washburg, Cleveland, Ohio

The term coon did not originally appear as a racial slur term for a Black American, though over a short period of time it evolved into that. In early minstrel songs, the "coon" was reference to a raccoon, whose meat was supposedly preferred by plantation slaves. In many cases, for unknowing composers, the term "coon" became entangled with the 'possum, also thought to be a preferred food source. Apparently, many composers were not very familiar with American wildlife and could not tell the difference. As a result, "coon" and "possum" were often used in the same context. The earliest use of the possum term in a song was in the 1830 work by Charles Matthews, A Possum Up A Tree. By the mid 19th century, coon and possum songs were a regular part of the musical scene, most often heard performed in minstrel shows.

As early as 1793, we see depictions of African Americans in songs for comic operas in America. Perhaps the earliest was the song Poor Black Boy from the Stephen Storace production, The Prize. About that same time, Charles Dibden produced Yanko Dear in which he featured black slaves as minor characters. In both cases, the music was deliberately simple and included exaggerated dialect lyrics, neither of which had any relationship to true African American style or speech.

In 1822, an English stage star, Charles Matthews, came to the U.S. and became enamored with the speech patterns and physical characteristics of American blacks. He began to incorporate skits, mock lectures and songs drawing on his view of black culture and as a result, he really is responsible for the trend in stage impersonation of African Americans during the early 19th century. In 1828, Thomas Dartmouth Rice introduced the song Jim Crow to his audiences as a part of his impersonation of an old black man. The song became an immediate hit and was widely distributed, becoming one of the first large distribution sheet music songs in America. Rice's success spurred other performers to impersonate Blacks and soon, entire troupes of performers did, beginning with the Virginia Minstrels in 1843. Soon, the American stage was filled with groups performing in blackface and performing entire shows made up of comic dialogs, skits, dance and songs about Black Americans. Some of the names of these groups live on today with such names as the Christy Minstrels and the Kentucky Minstrels. I think it wise to state here that the term "Minstrel" is not exclusively a blackface performer. That term has been in use for centuries and according to the Miriam Webster Dictionary is: "one of a class of medieval musical entertainers; especially: a singer of verses to the accompaniment of a harp." In other words, a musician. It is only when minstrel groups began their blackface performances that the term took on its more unsavory connotation in today's lexicon.

Unfortunately, the minstrel show became the most popular and distinctive product of the American entertainment scene and reached a new peak of popularity after the Civil War. Much to our embarrassment now, when the English were introduced to Rice's music and performances by the Virginia Minstrels in 1843, they viewed the music and performances as characteristic American music. Perhaps the most ironic thing about that is that many of the early minstrel songs, including the lauded Jim Crow, were actually based on the melodic foundations of English folk songs!! After these early beginnings, the Minstrel show settled in as an American Institution and coon songs flourished. By 1880, the term was used as a disparagement of Blacks in general and the songs took on a rather ugly tone also. Some mocked Black's social aspirations such as The Full Moon Union (1880) by Edward Harrigan and David Braham in which they said:

Dere isn't a coon

But what am a luminary in

A half a quarter moon.

A political song from the same year Ef de Party Wins points out the Black's loss of political and social influence at the end of Reconstruction. A flood of songs poured into the popular repertoire from this period on with titles such as The Dandy Coon's Parade, Oh Mr. Coon and The Coons Are On Parade. Composers capitalized on the fad by adding words typical of coon songs to previously published songs and rags. According to the New Grove Dictionary of American Music, though the ragtime elements of syncopation and harmony were borrowed for the coon song style, it is incorrect to consider them synonymous. We can clearly see fundamental differences in form, style and most of all, mood, that separates the two.

In Vaudeville, coon songs also flourished and a rather odd performance convention emerged; white females became the favored deliverers and were called "coon shouters." Foremost among the coon shouters was one May Irwin. Her performance of the Charles Trevathan hit The Bully Song (1896) was influential in establishing the stereotype of the razor toting, jealously belligerent black male. Also, this song has perhaps the worst racist lyrics of any song I have seen for a while. Once this level of ugliness was reached, it seemed that composers piled it on higher and deeper. Other coon songs soon exploited every conceivable black characteristic, real or imagined, for its comic possibilities. African-American aspirations to a place in society, food preferences, the imagined inclination for crime, and gambling all were exploited. The final insult was a number of songs where there was an imagined desire by all African Americans to become white as in the song, She's Gettin' Mo' Like The White Folks Every Day.

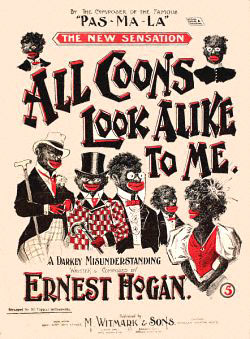

Sadly, even black songwriters produced songs as fully demeaning of their own race as those by white composers. The worst of these was Ernest Hogan's All Coons Look Alike To Me. The most prolific of the black composers to join in was Bob Cole who wrote dozens of songs such as No Coons Allowed and I Wonder What The Coon's Game Is?

Just as with the earlier minstrel shows, skits, entertainers and entire shows were developed from the coon song and many coon songs found their way into the legitimate theater as a part of productions. Even the great John Philip Sousa's famous band popularized some of the melodies and performed a number of them both at home and abroad. One of Sousa's assistants, Arthur Pryor, even composed some coon songs himself to keep the supply coming to the band. At the peak of its popularity, the coon song was everywhere and just about every songwriter in the country worked to fill the seemingly insatiable demand.

In their time, coon songs spoke volumes about white attitudes towards African Americans. Unfortunately, in many cases they also spoke volumes about some black composers' sense of personal pride and self image. They are an historical document that clearly shows white attitudes and the terribly oppressive social world that African Americans had to cope with. There seemed to be a piling-on mentality that simply escalated what started as a cute novelty song into a national obsession that in the end is a complete and abject embarrassment. How we could ever let a musical fad reach the levels it did is hard to even begin to understand in today's society. (Yet, the trend today of some Rap "music" is in many respects even worse. Coon songs were written in ignorance, much of today's Rap is written with malice, forethought and pure hatred in mind). Because of the lyrics in Coon songs, none of these songs are seen or performed today as they were originally written. It is even with some trepidation that we have dared to perform a few of them here at ParlorSongs. But, we do believe it is a chapter in our musical history that should not and cannot be swept under the rug. It seems a shame to have an entire genre of song lost to today because of the words, yet we could not tolerate a resurgence. (Let us hope the same happens with today's "hate songs"). The loss for us is certainly not in the lyrics but in losing the incredible musical richness of some of the songs that for a time, were the most popular and hottest selling hits in American popular music.

May 2005 response by

The Parlor Songs Association, Inc.

Richard A. Reublin and Robert L. Maine