Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

Who was the "Jackie Robinson" of the NBA? Why doesn't he get any attention?

-- Travis Crosetti, Lemont, Illinois

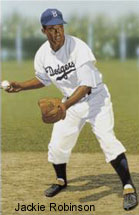

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson (1919-1972) made his debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers, making him the first African American to play major league baseball in the 20th century. Branch Rickey, the general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, wanted to break major league baseball's rigid but unwritten rule that barred Black players. He offered Robinson the chance to break the "color line" with this condition: Robinson could not respond angrily or aggressively to the expected racial abuse. Robinson agreed.

A fiercely proud man, Robinson endured racial taunts and threats from fans, reporters, and opposing players -- and, initially, his teammates. A group of Dodger players, most notably Dixie Walker, threatened to strike rather than play with a Black player. They relented after the Dodger management suggested they find positions with other teams. Pee Wee Reese, the team's shortstop and a native of Kentucky, supported Robinson and became his friend. Often, the opposing team would yell racist slurs at Robinson throughout the game and many pitchers threw at (and hit him); nevertheless, he excelled.

In his first season, Robinson played in 151 games, with a .297 batting average, and he led the National League with 29 stolen bases. He was awarded the Rookie of the Year award. In 1949 he was named the National League's Most Valuable Player after leading the league with a .342 batting average. He played his entire 10-year career (1947-56) with the Brooklyn Dodgers, setting fielding records and earning the reputation as a dynamic base stealer. In 1962 he became the first Black American inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. His career was relatively short but the role he played in changing major league sports and the larger society was enormous.

One could argue that Robinson's "dignified" response to racist taunts and threats foreshadowed the actions of civil rights protestors in the 1950s and 1960s. For the first two years of his major league career, Robinson responded to the racist attacks by excelling on the field. If a pitcher hit him with a pitch, he ran to first, and then stole second base -- and often third base. However, by 1949, Robinson had grown tired of the racial slurs, bean balls, and death threats. He began to speak publicly against racism in baseball and in the larger society. He would continue to speak against segregation until his death in 1972.

On April 26, 1950, Harold Hunter, from North Carolina College (now North Carolina Central University), became the first African American to sign a training camp contract with a team from the National Basketball Association (NBA). He was signed by the previously all-White Washington Capitols. Hunter, a 5-foot-9-inch point guard, had helped lead his college team to the championship of the Colored Intercollegiate Athletic Association. Unfortunately for him, the Capitols cut him during training camp, and he never played in an NBA game. Later, he excelled as a coach, becoming, in 1968, the first African American to coach the U.S. Olympic basketball team. Although he was the first Black to sign an "official" contract with an NBA team, he cannot be considered the "Jackie Robinson" of the NBA.

The NBA's color line was broken in 1950 by three Black men: Chuck Cooper, Earl Lloyd, and Nat "Sweetwater" Clifton. Cooper, a 6-foot-5-inch forward from Duquesne College, was the first African American to be drafted by an NBA team. He averaged 9.5 points and 8.5 rebounds for the Boston Celtics. In that same year, Earl Lloyd from West Virginia State was drafted by the Washington Capitols. Lloyd became the first African American to play in an NBA game when he played for the Capitols against the Rochester Royals on October 31, 1950. The Capitols folded during Lloyd's rookie season, but he joined the Syracuse Nationals the next season. During the 1954-55 season, Lloyd averaged 10.2 points and 7.7 rebounds, helping the Nationals win the NBA title. Lloyd retired in 1960 at the age of 32, ending his career with the Detroit Pistons, and finishing with career averages of 8.4 points and 6.4 rebounds. After spending a decade as a scout and assistant coach, Lloyd became the first Black coach of the Pistons during the 1971-72 season.

Sweetwater Clifton left the Harlem Globetrotters in 1950 to sign a contract with the New York Knicks. He helped the Knicks reach three consecutive NBA Finals and averaged 10 points and 8.4 rebounds. It was only because of the order in which the teams' season openers fell that Lloyd was the first to play in an NBA game. The date, October 31, 1950, was one day ahead of Charles Cooper's debut with the Boston Celtics and four days before Clifton played with the Knicks. Later that season, Hank DeZonie was signed by the Tri-Cities Black Hawks. He played in five games. He had previously played pro basketball in the semi-integrated National Basketball League -- one of the two leagues that merged to form the NBA.

The fact that several Blacks joined the NBA in the same year kept any one Black player from being the sole recipient of racial resentment. And there was some opposition: racial slurs, threats, spitting. There were also the reminders of Jim Crow laws and segregation. In Lloyd's words:

"I don't think my situation was anything like Jackie Robinson's -- a guy who played in a very hostile environment, where even some of his own teammates didn't want him around. In basketball, folks were used to seeing integrated teams at the college level. There was a different mentality. But of course, the team did stay and eat in some places where I wasn't welcome. I remember in Fort Wayne, Ind., we stayed at a hotel where they let me sleep, but they wouldn't let me eat. They didn't want anyone to see me. Heck, I figured if they let me sleep there, I was at least halfway home. You have to remember, I grew up in segregated Virginia, so I had seen this stuff before. Did it make me bitter? No. If you let yourself become bitter, it will eat away at you inside. If adversity doesn't kill you, it makes you a better person."

Cooper, Lloyd, and Clifton were solid players who paved the way for Allen Iverson, Kevin Garnett, Tim Duncan and all the Black athletes who play and will play in the NBA. Like Jackie Robinson, they endured racial abuse -- and they did not retaliate. Baseball was America's pastime, and Robinson's breaking of the color line had tremendous societal consequences, including opening the door for Blacks to enter the professional leagues of other sports.

December 2005 response by

David Pilgrim

Curator

Jim Crow Museum