Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

The Jim Crow era in the United States extended from the mid-1870s to the mid-1960s; consequently, most of the racist artifacts in the Ferris State University Jim Crow Museum were produced and distributed during that period.

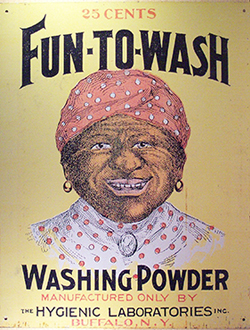

The museum's holdings include Jim Crow memorabilia, for example, a "Whites Only" sign and "Colored" theater tickets. These artifacts are the types of objects that most observers associate with Jim Crow laws and etiquette. Jim Crow was more, however, than de jure and de facto segregation reflected by insulting public signs and theater tickets. It was the systemic degrading of black people. This degradation was expressed in everyday items, including, but not limited to ashtrays, postcards, Halloween masks, incense burners, fishing lures, sheet music, detergent boxes, wall clocks, jewelry, and toys. Black men were depicted as slow talking, childlike servants; wide-eyed, big lipped buffoons; or menacing, subhuman brutes. Black women were portrayed as fat, ugly, desexed pretend-mothers or near-white, sex crazed, self-loathing victims. Black children were portrayed as nameless, naked, miniature buffoons.

Millions of anti-black items were produced during the Jim Crow period, and these items served to justify prejudice and discrimination against African Americans. If black adults were childlike, for example, then they should not be allowed to vote, serve on juries, or become police officers or teachers. The anti-black items both shaped and reflected attitudes toward black people.

Racist items are still being produced, distributed, and sold. These newly created objects may be categorized this way: counterfeit antiques, honest reproductions not designed to deceive, updated racist objects, new black caricatures, and white supremacy items. The purpose of this essay is to explore these new expressions of racism and to explain their inclusion in the Jim Crow Museum.

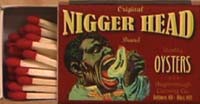

Racist collectibles are highly sought after by collectors. There are about fifty thousand collectors of "Black Memorabilia" -- an umbrella term which includes any object related to the African American experience.1 Black memorabilia, especially the older artifacts, include a disproportionately large number of racist anti-black collectibles. Since the 1970s there has been an upsurge in interest in black collectibles, especially blatantly racist objects. The high demand has led to an escalation of prices. Stacy Ayers, a college administrator and collector, has said, "Black memorabilia used to come a dime a dozen. Now there are so many collectors, many items have become hot commodities" (Alexander, 2000, p. 261). Black lawn jockeys, for example, were sold for less than $30 in the 1970s; however, these items now sell for as much as $500 each. Rose Echols, owner of Echols Antiques & Gifts in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, has said "Postcards that were priced at a half a cent to 3 cents are now selling for $5 to $30 and up. The little salt and pepper shakers that sold for 50 cents to $1 are selling for $30 to $50. Cookie jars that might have cost $5 -- now most of them are over $500" (Demski, 1998). Some black artifacts are very expensive, for example, an 1890s mechanical bank, "The DarkTown Battery," is valued at $5,700. An 1887 "Nigger Head" cap gun recently sold for $415; a Coon Chicken Inn dinner plate sold for $431; and a Little Black Sambo block sold for $305 (Deen, n.d.). Two of the largest auction houses, Christie's East and Sotheby's, have held Black Memorabilia auctions.

eBay, a leading Internet auction service, typically has 3,000-4,000 "Black Americana" auctions daily. On December 4, 2000, a 1968 copy of Agatha Christie's Ten Little Niggers sold for $76 on eBay. On December 6, 2000, a "lynching" scrapbook of newspaper clippings and photographs sold for $909. On December 13, 2000, a well worn 1897 book, Comical Coons, sold for $355; a 1930s sheet of music with a Ku Klux Klan theme sold for $100.19; and, a 1950s Golliwog clacker metal toy sold for $85. These prices are typical of the prices realized at other Internet auction services, and are much lower than the prices listed on the webpages of independent Internet dealers.

Recent Black Memorabilia shows have attracted thousands of buyers. Wyatt Houston Day promotes an annual show at the Swann Gallery in Manhattan, New York. In February, 2000, his show generated $261,556 in sales, including a 1931 Jim Crow sign,"We Serve Colored Carry Out Only," which sold for $805. Leonard Davis, the co-editor of a Black Memorabilia price guide, says that items like human branding irons have sold for $1,000 at the Bronx-based Black Memorabilia Collectors Association shows. He claims that Aunt Jemima cookie jars sell for as much as $1,800 each.

The increased demand for racist items has resulted in a proliferation of counterfeits. The Antique & Collectors Reproduction News reports that Gold Dust Soap boxes (showing two naked Black children) have been so frequently counterfeited that most of the boxes offered for sale are fakes.2 Almost all heavily coveted "black collectibles" have been reproduced, especially slavery-related items, segregation signs, advertising pieces, figurines, toys, and mechanical banks. In 2000, King Richard's Antique Center offered an early-1900s Jolly Nigger Bank for $649 through www.krantiques.com. The high price may explain the proliferation of counterfeit Jolly Nigger Banks and other black banks being sold in antique shops and on the Internet.

Anti-black ephemera seems particularly prone to forgery. Almost all black-related postcards, posters, and advertising signs have been counterfeited. Cream of Wheat advertisements, Coon Chicken Inn hand fans, Bull Durham posters, and Aunt Jemima ephemera have all been reproduced in great numbers. The counterfeit items are often put into smoke houses to color the paper, thereby giving the appearance of being aged. There are numerous counterfeit "Whites Only" and "Colored Served In Rear" signs offered for sale by Internet auction houses. These paper signs show brown edges, but the centers of the signs are not discolored.

Blatantly racist items are often reproduced. One of the most reproduced paper items is an 1890s picture of naked black children climbing a fence to get to a swimming hole. The caption reads: "Alligator Bait."3 Recent reproductions have changed the caption to "Last One In's A Nigger," and appear on postcards, prints, and posters. Items with the word "nigger" on them are highly sought after by collectors, generally bring high prices, and are frequently reproduced.

Black Enterprise magazine (Alexander, 2000, p. 261) and the Wall Street Journal (Hernandez, 1992, p. B1 (W), p. B1 (E), Column 4) have touted Black Memorabilia as worthwhile investments. Essence, a leading Black magazine, even gave a short tutorial on how to shop for these items (Greenwood, 1997, p. 16). Black people are now as likely as white people to collect black memorabilia -- including racist memorabilia -- and celebrities such as Oprah Winfrey and Spike Lee are avid collectors. Although some black people collect racist items as "investments," many black people, including Winfrey and Lee, collect the material to remind themselves and others of America's racist past. These collectors, regardless of their motivations, are exhausting the available supply of original black-related items. The price of authentic black-related memorabilia has escalated as fewer older pieces remain on the market. This escalation in prices has significant consequences: Jim Crow era artifacts are increasingly found in the elite collections of wealthy individuals or organizations, and the demand for cheaper Jim Crow styled items has spurred a flourishing reproductions market.

The Fiedler & Fiedler Tool and Die Company of Dayton, Ohio, made Aunt Jemima and Uncle Mose items in the late 1940s. These items -- cookie jars, salt and pepper shakers, condiment figures, and dolls -- were promotional giveaways from the Quaker Oats Company. They are highly collectible today, with many selling for hundreds of dollars. Their popularity has encouraged reproductions, both counterfeit and honest. The Fiedler & Fiedler Die Company also made advertising items for Luzianne Coffee, especially salt and pepper shakers. Reproductions are on the market and are recognized easily because the original plastic Luziannes have green skirts and the reproductions do not (Reno, 1986, p. 94). The Nelson McCoy Pottery Company produced many black mammy cookie jars beginning in the 1920s. These popular items are often fraudulently reproduced.

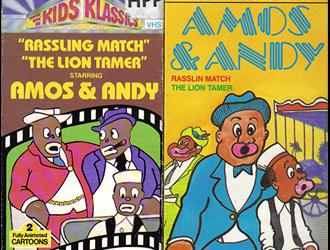

Reproductions, honest or not, bring Jim Crow images into the present. Today's children can watch videotapes of The Little Rascals and Amos 'n' Andy -- the same episodes their parents and grandparents watched. These videotapes are mass produced and sold by Big Lots discount stores, Cracker Barrel restaurants, and other mainstream businesses. Buckwheat memorabilia is popular with collectors. The obese, handkerchief-headed mammies and grinning, lazy Coons displayed on postcards, banks, ashtrays, detergent boxes, and toys during the Jim Crow period are being reproduced and distributed to a new generation. There is a Jolly Nigger Bank, for example, currently being produced in Taiwan for the American market. It is painted red, white, and black, unlike older variations of the bank. This cheaper bank sells for $15-25 dollars, making it more affordable than the original. Like its older counterparts, this newly reproduced bank is the bust of a caricatured black man: jet black skin, oversized white eyes, smiling clown-like lips.

In 1994 Mother Productions reproduced forty-two early 1900s postcards and marketed them as "Coloreds Only: Black Bashing Art." These are Jim Crow era images brought into the present.

Old racist images are often placed on new objects. Images of Sambos, Mammies, Toms, and Coons are reproduced on new wall clocks, posters, metal tins, watches, ashtrays, plates, and postcards. The AAA Sign Company of Coitsville, Ohio, makes and sells tin signs. These signs have anti-black images found originally on 1920s-1950s postcards, trade cards, game boards, and food labels. In 1940, All-Metals Products Company of Wyandotte, Michigan, marketed a "Sambo Target" for use with their toy pistol set. A gap-toothed, wide-eyed "picaninny" was the centerpiece of the brightly lithographed, metal target board (Mercier, n.d.). He is straddling a target. In 1994, the AAA Company reproduced the Sambo dart board as a decorative tin sign. It typically sells for $15 to $25 on Internet auctions -- and $25 to $45 in stores specializing in collectibles

One Texas dealer takes old anti-black trade cards, postcards, magazine advertisements, and food can labels and reproduces the images on the covers of wall clocks, watches, and keychains. This dealer also sells matchboxes in sets of three. On the cover of one set are old Cream of Wheat magazine advertisements, obviously, greatly reduced in size. Another set includes three matchboxes with Nigger Head Shrimp, Nigger Head Oysters, and Negro Head Oysters, respectively. These images were originally on food can labels. The dealer reproduced the images, reduced them, and put the images on matchboxes. This same dealer sells matchboxes with Mammy Brand Oranges on the cover.

Computer mousepads are a popular medium for old racist images. There are mousepads with images taken from the book Little Black Sambo, a poster advertising Uncle Tom's Cabin, and a magazine advertisement for Amos 'n' Andy. Any image originally produced on paper can be reproduced on mousepads.

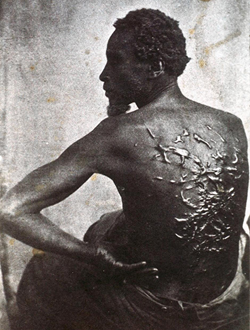

There is a well-known picture of a formerly enslaved man Gordon, his back covered with horrific scars, the result of many whippings. This image has been reproduced on metal tin signs. The back of the sign reads:

$39.95

Collector Metal

Photo-Advertising Signs

The Old Photo Chest of America

Concord, Massachusetts

Limited Edition

10,000 Worldwide

Black Slave with Whip Scars #35

Copyright 1994

The same company sells a tin sign which shows two black people lynched. Both images -- the scarred man and the lynching victims -- are also reproduced on keychains. These items were sold on eBay in 1999.

The Doped Rastafarian is another new anti-black caricature. This image, found mainly on tee shirts and beach towels, has two variations. One version has a very thin black man, his hair in dreadlocks, legs spread, eyes wild, and a marijuana cigarette in his mouth or hand. He is high but harmless. The second version shows a heinous figure, a combination Tasmanian devil and drug user. He is abnormally short, with fangs. Tee-shirts with both versions of the Doped Rastafarian are popular on college campuses.

New anti-black images are also found in the popular children's games Pokemon and Dragonball Z. The Pokemon character Jynx has jet-black skin, large protruding pink lips, gaping eyes, a straight blond mane, and a full figure, complete with cleavage and wiggly hips. Carole Boston Weatherford (2009), a cultural critic, described Jynx as "a dead ringer for an obese drag queen" (p. 9).

Mr. Popo, a Dragonball Z character, is a rotund genie, dwarfish, with pointed ears, jet-black skin, and large red lips. He is a loyal servant.

For further discussion on the Pokemon Jynx character, see September 2009 Question of the Month.

The Internet affords white supremacist organizations unparalleled opportunities to publicize their beliefs. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, there are more than 500 racist and neo-Nazi groups in the United States. (http://www.splcenter.org/) Don Black, a former Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan, established the first racist site on the World Wide Web, Stormfront, in 1995. Stormfront added a page counter on March 27, 1995. On December 17, 2000, the counter showed 3,577,849 hits (visits to the site).4 "We are simply a White pride site," he said. "We believe White people have the right to promote their interests and their values and their heritage just as other races have the same rights" (Marriott, 1999). Black said that, before the Internet, people who shared white power beliefs had to use leaflets, small newspapers, and local rallies to spread their ideas. But today, he noted, a relatively inexpensive Web site can reach millions. He spends about $1,000 a month to operate Stormfront. Black's organization owns its own computer servers and is, therefore, not dependent on Internet service providers. Stormfront offers for sale "White Power" products, for example books, videos, and jewelry.

Micetrap Distribution http://www.micetrap.net was another website which sells anti-black products. In addition to white power flags, books, and videos of Skinhead musical concerts, this organization also sells remakes of old racist songs. A Johnny Rebel CD, for example, includes these songs, "Some Niggers Never Die," "Coon Town," "Cowboys & Niggers," "We Don't Want Niggers In Our Schools," and "Move Them Niggers North." This site added a counter on May 15, 1996. On December 16, 2000, the counter indicated 2,588,980 visits to the site. Heritage Front, which billed itself as "Canada's Largest Racialist Group," sold magazines, musical videos, books, and business cards over the Internet. Most white supremacist organizations sell merchandise, and much of this merchandise dehumanizes or belittles minorities, especially black people and Jews.

Tee-shirts with the words, "Ain't RACIST Just Never Met a NIGGER I liked," or "Martin Luther Coon" are found at many white power sites. Many of these sites also include "nigger jokes" and anti-black cartoons.5 These cartoons are vulgar and portray traditional anti-black stereotypes. The cartoons on these websites are often reproduced on posters.

One consequence of the American Civil Rights Movement was that racist artifacts fell into disfavor. From the early 1960s to the mid-1970s, many Americans were embarrassed to own items which caricatured black people. Flea market and antique dealers hid anti-black items. In the late 1970s astute antique dealers recognized that once-plentiful anti-black items were increasingly rare -- a large number having been destroyed. These dealers, primarily but not exclusively white, began collecting Black Memorabilia, including the racist pieces. This trend was helped by the publication of several Black Memorabilia price guides in the 1980s. These price guides alerted the larger antique collecting public to the investment potential of anti-black items and segregation memorabilia. In 1984, Malinda Saunders, a black antique dealer, promoted the nation's first Black Memorabilia show. Most of the show's buyers were white. Saunders' shows continue; however, black people now constitute the majority of the show's buyers (Friz, 1997). By the late 1980s, a dozen additional price guides were on the market, and Black Memorabilia was being openly sought by thousands of collectors. Saunders and other elite collectors of Black Memorabilia were profiled in national magazines, on syndicated talk shows, and in local museums. Black Memorabilia became one of the fastest growing segments of the collecting community -- and racist artifacts were especially popular.

Reproductions -- whether counterfeits or legitimate -- and updated racist objects bring Jim Crow era images into the 21st century. These are nearly exact replicas of the Sambos, Mammies, Coons, Toms, and Brutes of pre-Civil Rights movement America. These images are included in the Jim Crow Museum because they are Jim Crow images. The modern caricatures continue the tradition of dehumanizing black people. These caricatures are often variants of Jim Crow era stereotypes, albeit mixed and updated. The Plain Brown Rapper, for example, may be seen as a Coon/Brute hybrid. White supremacist groups were also integral parts of the Jim Crow period -- their violence and threats of violence undergirded the Jim Crow system. Their products, sold on their websites, still promote white power while debasing black people and other minorities.

Clearly, there are several markets for anti-black products. Collectors can be divided into four categories. "Nostalgic Collectors" buy anti-black items because it reminds them of a happier time. The majority of these collectors are white. "Liberator Collectors" purchase racist memorabilia to destroy it. There are black and white members of this category. "Heritage Collectors" are black people who believe that all Black Memorabilia, even the derogatory objects, should be preserved. "Investor/Speculators" are profit-seeking buyers. Most of these collectors are white, but a growing number of black people fit into this category.

Books with racist jokes remain popular. Blanche Knott's Truly Tasteless Jokes series

and Maude Thickett's Outrageously Offensive Jokes series were bestsellers.6 The jokes are similar to the ones found on the Web pages of White supremacy groups,

previously at http://www.jeack.com.au/~jed/woodpile.htm.

Books with racist jokes remain popular. Blanche Knott's Truly Tasteless Jokes series

and Maude Thickett's Outrageously Offensive Jokes series were bestsellers.6 The jokes are similar to the ones found on the Web pages of White supremacy groups,

previously at http://www.jeack.com.au/~jed/woodpile.htm.

R. Crumb's comics7 include many racially stereotypical characters, including "Salty Dog Sam," a Coon

caricature, "Angelfood McSpade," an Amazon-Savage hybrid who talks like a Mammy, and

"Jockey boy," a dwarf Coon caricature dressed like the lawn ornament (Crumb, 1996).

Crumb's supporters claim that he is a satirist.8 Crumb's writings, many originally published in the 1960s and 1970s, are being reproduced.

His story, "When The Niggers Take Over America," is reminiscent of The Birth of a

Nation. In both, black people are portrayed as thugs, rapists, murderers desiring

to enslave white people (Crumb, 1995). For an excellent history of racism in comic

books, see From "Under Cork" to Overcoming: Black Images in the Comics.

The selling of anti-black items today sometimes resembles the selling of anti-black items during the period of segregation. Racist items are sold openly; they are sold nationally. Even the language used in the advertisements is reminiscent of 1950s sales. For example, some eBay dealers use the word nigger in their auction titles and descriptions, even when the word is not a part of the item's name. One item for sale was described by the dealer as a "black nigger boy eating watermelon figure." The dealer used nigger in the title to attract more potential buyers. eBay has a search engine which allows customers to search for specific items, for example, items with nigger in the title, like the Jolly Nigger Bank described earlier. "It has nothing to do with prejudice," said the dealer, "I did hesitate to do it, but I think it has drawn more attention to the auction."9

© Dr. David Pilgrim, Professor of Sociology

Ferris State University

Jan., 2001

Edited 2024

1 Some antique dealers define Black Memorabilia as antique items at least thirty years old, and label newer Black-related items as Black collectibles.

2 See Counterfeit Black Ephemera. Coxsackie Antique Center. Retrieved fromhttp://www.coxsackie.com. The ACRN webpage ishttp://antiqueandcollectible.com.

3 This print was copyrighted by McGrary & Branson in 1896. The copyright was often violated.

4 Obviously, not all the people who visit the site support Stormfront's views on race and racial relations.

5 See, for example,http://www.resist.com/politicalcartoons.html. This site is sponsored by the White Aryan Resistance organization. Their site includes both anti-Black and anti-Jew cartoons.

6 See, for example, Knott (1983) and Thickett (1984).

7 Crumb, the originator of the slogan, "Keep on Truckin', has appeared in Newsweek and People magazines. His work has been displayed in the Museum of Modern Art in New York and a movie was made about his life.

8 A good debate about whether Crumb is a racist or simply an unconventional cartoonist who satirizes racism is found athttp://archives.tcj.com/2_archives/i_spiegelman.html. Some of his supporters claim Crumb is a racist but it doesn't matter because he hates everyone. See, Matt Freestone, "Crumb -- Terry Zwigoff" athttp://www.furthermore.org.uk/static/phoenix/sffilm.htm.

9 This practice was common on Ebay. The item mentioned here was described in an Internet article (Gurnon, 1999). Ebay has since changed its policy and does not allow use of racial slurs. Seehttp://pages.ebay.com/help/policies/offensive.html.

Alexander, G. (2000, February). Collecting our history. Black Enterprise, 30(I7).

Crumb, R. (1995). R. Crumb's America. San Francisco, CA: Last Gasp.

Crumb, R. (1996). R. Crumb's Carload O' Comics. New York, NY: Belier Press.

Deen, E.R. (n.d.). Black memorabilia, Collectors News: Internet edition. Retrieved from http://publications.kaleden.com/articles/875.html.

Demski, J. K. (1998, May 10). Black collectibles: African-American memorabilia find many homes. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Friz, D. (1997, September). Black memorabilia & artifacts show. Maine Antique Digest. See https://ferris.edu/jimcrow/links/maine/.

Greenwood, M. (1997, February). Collecting Black memorabilia with Althea Burton. Essence, 27(10).

Gurnon, E. (1999, September 15). Racial items on Internet auction site raise questions. San Francisco Examiner.

Hernandez, C. (1992, August 10). Black memorabilia find big demand. The Wall Street Journal.

Knott, B. (1983). Truly tasteless jokes three. New York, NY: Ballantine Books.

Marriott, M. (1999, March 18). Rising tide: Sites born of hate. The New York Times On The Web. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/library/tech/99/03/circuits/articles/18hate.html.

Mercier, D. (n.d.). From hostility to reverence: 100 years of African-American imagery in games. See https://ferris.edu/jimcrow/links/games/.

Reno, D. E. (1986). Collecting Black Americana. New York, NY: Crown Publishers.

Thickett, M. (1984). Outrageously Offensive Jokes II. New York, NY: Pocket Books.

Weatherford, C. B. (2000, May 4). Japan's bigoted exports to kids. Opinion section. The Christian Science Monitor.