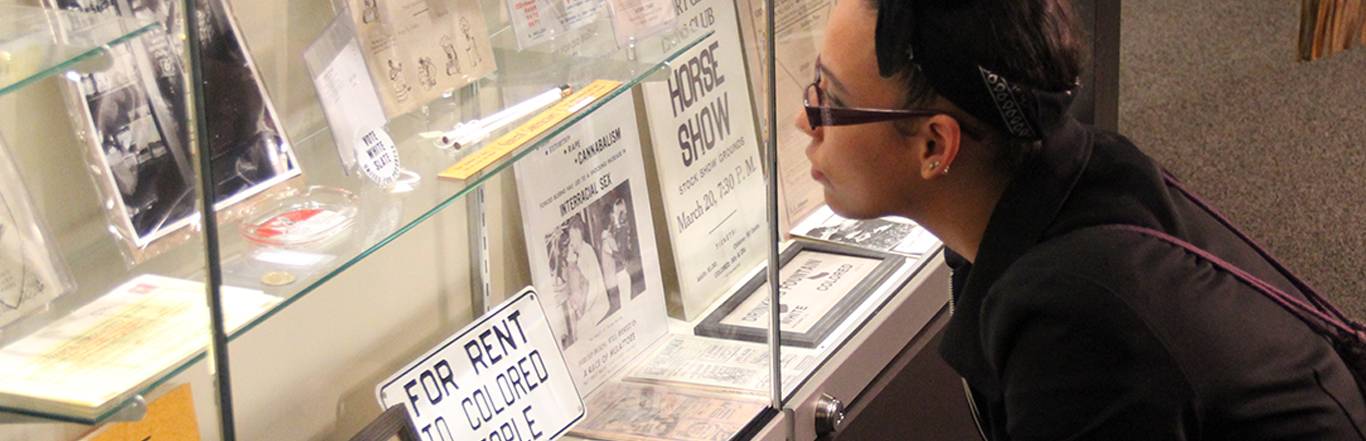

Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

Lydia Maria Child introduced the literary character that we call the tragic mulatto1 in two short stories: "The Quadroons" (1842) and "Slavery's Pleasant Homes" (1843). She portrayed this light skinned woman as the offspring of a white slaveholder and an enslaved black female. This mulatto's life was indeed tragic. She was ignorant of both her mother's race and her own. She believed herself to be white and free. Her heart was pure, her manners impeccable, her language polished, and her face beautiful. Her father died; her "negro blood" discovered, she was remanded to slavery, deserted by her white lover, and died a victim of slavery and white male violence. A similar portrayal of the near-white mulatto appeared in Clotel (1853), a novel written by black abolitionist William Wells Brown.

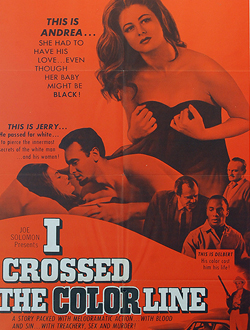

A century later literary and cinematic portrayals of the tragic mulatto emphasized her personal pathologies: self-hatred, depression, alcoholism, sexual perversion, and suicide attempts being the most common. If light enough to "pass" as white, she did, but passing led to deeper self-loathing. She pitied or despised black people and the "blackness" in herself; she hated or feared white people yet desperately sought their approval. In a race-based society, the tragic mulatto found peace only in death. She evoked pity or scorn, not sympathy. Sterling Brown summarized the treatment of the tragic mulatto by white writers:

White writers insist upon the mulatto's unhappiness for other reasons. To them he is the anguished victim of divided inheritance. Mathematically they work it out that his intellectual strivings and self-control come from his white blood, and his emotional urgings, indolence and potential savagery come from his Negro blood. Their favorite character, the octoroon, wretched because of the "single drop of midnight in her veins," desires a white lover above all else, and must therefore go down to a tragic end.(Brown, 1969, p. 145)

Vara Caspary's novel The White Girl (1929) told the story of Solaria, a beautiful mulatto who passes for white. Her secret is revealed by the appearance of her brown-skinned brother. Depressed, and believing that her skin is becoming darker, Solaria drinks poison. A more realistic but equally depressing mulatto character is found in Geoffrey Barnes' novel Dark Lustre (1932). Alpine, the light-skinned "heroine," dies in childbirth, but her white baby lives to continue "a cycle of pain." Both Solaria and Alpine are repulsed by black people, especially black suitors.

Most tragic mulattoes were women, although the self-loathing Sergeant Waters in A Soldier's Story (Jewison, 1984) clearly fits the tragic mulatto stereotype. The troubled mulatto is portrayed as a selfish woman who will give up all, including her black family, in order to live as a white person. These words are illustrative:

Don't come for me. If you see me in the street, don't speak to me. From this moment on I'm White. I am not colored. You have to give me up.

These words were spoken by Peola, a tortured, self-hating black girl in the movie Imitation of Life (Laemmle & Stahl, 1934). Peola, played adeptly by Fredi Washington, had skin that looked white. But she was not socially white. She was a mulatto. Peola was tired of being treated as a second-class citizen; tired, that is, of being treated like a 1930s black American. She passed for white and begged her mother to understand.

Imitation of Life, based on Fannie Hurst's best selling novel, traces the lives of two widows, one white and the employer, the other black and the servant. Each woman has one daughter. The white woman, Beatrice Pullman (played by Claudette Colbert), hires the black woman, Delilah, (played by Louise Beavers) as a live-in cook and housekeeper. It is the depression, and the two women and their daughters live in poverty -- even a financially struggling white woman can afford a mammy. Their economic salvation comes when Delilah shares a secret pancake recipe with her boss. Beatrice opens a restaurant, markets the recipe, and soon becomes wealthy. She offers Delilah, the restaurant's cook, a twenty percent share of the profits. Regarding the recipe, Delilah, a true cinematic mammy, delivers two of the most pathetic lines ever from a black character: "I gives it to you, honey. I makes you a present of it." While Delilah is keeping her mistress's family intact, her relationship with Peola, her daughter, disintegrates.

Peola is the antithesis of the mammy caricature. Delilah knows her place in the Jim Crow hierarchy: the bottom rung. Hers is an accommodating resignation, bordering on contentment. Peola hates her life, wants more, wants to live as a white person, to have the opportunities that white people enjoy. Delilah hopes that her daughter will accept her racial heritage. "He [God] made you black, honey. Don't be telling Him his business. Accept it, honey." Peola wants to be loved by a white man, to marry a white man. She is beautiful, sensual, a potential wife to any white man who does not know her secret. Peola wants to live without the stigma of being black -- and in the 1930s that stigma was real and measurable. Ultimately and inevitably, Peola rejects her mother, runs away, and passes for white. Delilah dies of a broken heart. A repentant and tearful Peola returns to her mother's funeral.

Audiences, black and white (and they were separate), hated what Peola did to her mother -- and they hated Peola. She is often portrayed as the epitome of selfishness. In many academic discussions about tragic mulattoes the name Peola is included. From the mid-1930s through the late 1970s, Peola was an epithet used by black people against light-skinned black women who identified with mainstream white society. A Peola looked white and wanted to be white. During the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power Movement, the name Peola was an insult comparable to Uncle Tom, albeit a light-skinned female version.

Fredi Washington, the black actress who played Peola, was light enough to pass for white. Rumor has it that in later movies makeup was used to "blacken" her skin so white audiences would know her race. She had sharply defined features; long, dark, and straight hair, and green eyes; this limited the roles she was offered. She could not play mammy roles, and though she looked white, no acknowledged black was allowed to play a white person from the 1930's through the 1950's.

Imitation of Life was remade in 1959 (Hunter & Sirk). The plot is essentially the same; however, Peola is called Sara Jane, and she is played by Susan Kohner, a white actress. Delilah is now Annie Johnson. The pancake storyline is gone. Instead, the white mistress is a struggling actress. The crux of the story remains the light-skinned girl's attempts to pass for white. She runs away and becomes a chorus girl in a sleazy nightclub. Her dark skinned mother (played by Juanita Moore) follows her. She begs her mother to leave her alone. Sara Jane does not want to marry a "colored chauffeur"; she wants a white boyfriend. She gets a white boyfriend, but, when he discovers her secret, he savagely beats her and leaves her in a gutter. As in the original, Sara Jane's mother dies from a broken heart, and the repentant child tearfully returns to the funeral.

Peola and Sara Jane were cinematic tragic mulattoes. They were big screen testaments to the commonly held belief that "mixed blood" brought sorrow. If only they did not have a "drop of Negro blood." Many audience members nodded agreement when Annie Johnson asked rhetorically, "How do you explain to your daughter that she was born to hurt?"

Were real mulattoes born to hurt? All racial minorities in the United States have been victimized by the dominant group, although the expressions of that oppression vary. Mulattoes were considered black; therefore, they were enslaved along with their darker kinsmen. It was said, all slaves were "born to hurt," but some writers have argued that mulattoes were privileged, relative to dark-skinned black people. E.B. Reuter (1919), a historian, wrote:

In slavery days, they were most frequently the trained servants and had the advantages of daily contact with cultured men and women. Many of them were free and so enjoyed whatever advantages went with that superior status. They were considered by the white people to be superior in intelligence to the black Negroes, and came to take great pride in the fact of their white blood....When possible, they formed a sort of mixed-blood caste and held themselves aloof from the black Negroes and the slaves of lower status. (p. 378)

Reuter's claim that mulattoes were held in higher regard and treated better than "pure blacks" must be examined closely. American slavery lasted for more than two centuries; therefore, it is difficult to generalize about the institution. The interactions between slaveholder and the enslaved varied across decades--and from plantation to plantation. Nevertheless, there are clues regarding the status of mulattoes. In a variety of public statements and laws, the offspring of white-black sexual relations were referred to as "mongrels" or "spurious" (Nash, 1974, p. 287). Also, these interracial children were always legally defined as pure black people, which was different from how they were handled in other New World countries. A slaveholder claimed that there was "not an old plantation in which the grandchildren of the owner [therefore mulattos] are not whipped in the field by his overseer" (Furnas, 1956, p. 142). Further, it seems that mulatto women were sometimes targeted for sexual abuse.

According to the historian J. C. Furnas (1956), in some slave markets, mulattoes and quadroons brought higher prices, because of their use as sexual objects (p. 149). Some slavers found dark skin vulgar and repulsive. The mulatto approximated the white ideal of female attractiveness. All enslaved women (and men and children) were vulnerable to being raped, but the mulatto afforded the slave owner the opportunity to rape, with impunity, a woman who was physically white (or near-white) but legally black. A greater likelihood of being raped is certainly not an indication of favored status.

The mulatto woman was depicted as a seductress whose beauty drove white men to rape her. This is an obvious and flawed attempt to reconcile the prohibitions against miscegenation (interracial sexual relations) with the reality that white people routinely used black people as sexual objects. One slaver noted, "There is not a likely looking girl in this State that is not the concubine of a White man..." (Furnas, 1956, p. 142). Every mulatto was proof that the color line had been crossed. In this regard, mulattoes were symbols of rape and concubinage. Gary B. Nash (1974) summarized the slavery-era relationship between the rape of black women, the handling of mulattoes, and white dominance:

Though skin color came to assume importance through generations of association with slavery, white colonists developed few qualms about intimate contact with black women. But raising the social status of those who labored at the bottom of society and who were defined as abysmally inferior was a matter of serious concern. It was resolved by insuring that the mulatto would not occupy a position midway between white and black. Any black blood classified a person as black; and to be black was to be a slave.... By prohibiting racial intermarriage, winking at interracial sex, and defining all mixed offspring as black, white society found the ideal answer to its labor needs, its extracurricular and inadmissible sexual desires, its compulsion to maintain its culture purebred, and the problem of maintaining, at least in theory, absolute social control. (pp. 289-290)

George M. Fredrickson (1971), author of The Black Image in the White Mind, claimed that many white Americans believed that mulattoes were a degenerate race because they had "White blood" which made them ambitious and power hungry combined with "Black blood" which made them animalistic and savage. The attributing of personality and morality traits to "blood" seems foolish today, but it was taken seriously in the past. Charles Carroll, author of The Negro a Beast (1900), described black people as apelike. Regarding mulattoes, the offspring of "unnatural relationships," they did not have "the right to live," because, Carroll said, they were the majority of rapists and killers (Fredrickson, 1971, p. 277). His claim was untrue but widely believed. In 1899 a southern white woman, L. H. Harris, wrote to the editor of the Independent that the "negro brute" who rapes white women was "nearly always a mulatto," with "enough white blood in him to replace native humility and cowardice with Caucasian audacity" (Fredrickson, 1971, p. 277). Mulatto women were depicted as emotionally troubled seducers and mulatto men as power hungry criminals. Nowhere are these depictions more evident than in D. W. Griffith's film The Birth of a Nation (1915).

The Birth of a Nation is arguably the most racist mainstream movie produced in the United States. This melodrama of the Civil War and Reconstruction justified and glorified the Ku Klux Klan. Indeed, the Klan of the 1920s owes its existence to William Joseph Simmons, an itinerant Methodist preacher who watched the film a dozen times, then felt divinely inspired to resurrect the Klan which had been dormant since 1871. D. W. Griffith based the film on Thomas Dixon's anti-black novel The Clansman (1905) (also the original title of the movie). Griffith, following Dixon's lead, depicted his black characters as either "loyal darkies" or brutes and beasts lusting for power and, worse yet, lusting for white women.

The Birth of a Nation tells the story of two families, the Stonemans of Pennsylvania, and the Camerons of South Carolina. The Stonemans, headed by politician Austin Stoneman, and the Camerons, headed by slaveholder "Little Colonel" Ben Cameron, have their longtime friendship divided by the Civil War. The Civil War exacts a terrible toll on both families: both have sons die in the war. The Camerons, like many slaveholders, suffer "ruin, devastation, rapine, and pillage." The Birth of a Nation depicts Radical Reconstruction as a time when black people dominate and oppress white people. The film shows black people pushing white people off sidewalks, snatching the possessions of white people, attempting to rape a white teenager, and killing black people who are loyal to white people (Leab, 1976, p. 28). Stoneman, a carpetbagger, moves his family to the South. He falls under the influence of Lydia, his mulatto housekeeper and mistress.

Austin Stoneman is portrayed as a naive politician who betrays his people: white people. Lydia, his lover, is described in a subtitle as the "weakness that is to blight a nation." Stoneman sends another mulatto, Silas Lynch, to "aid the carpetbaggers in organizing and wielding the power of the vote." Lynch, owing to his "white blood," becomes ambitious. He and his agents rile the local black people. They attack white people and pillage. Lynch becomes lieutenant governor, and his black co-conspirators are voted into statewide political offices. The Birth of a Nation shows black legislators debating a bill to legalize interracial marriage -- their legs propped on tables, eating chicken, and drinking whiskey.

Silas Lynch proposes marriage to Stoneman's daughter, Elsie. He says, "I will build a black empire and you as my queen shall rule by my side." When she refuses, he binds her and decides on a "forced marriage." Lynch informs Stoneman that he wants to marry a white woman. Stoneman approves until he discovers that the white woman is his daughter. While this drama unfolds, black people attack white people. It looks hopeless until the newly formed Ku Klux Klan arrives to reestablish white rule.

The Birth of a Nation set the standard for cinematic technical innovation -- the imaginative use of cross-cutting, lighting, editing, and close-ups. It also set the standard for cinematic anti-black images. All of the major black caricatures are in the movie, including, mammies, sambos, toms, picaninnies, coons, beasts, and tragic mulattoes. The depictions of Lydia -- a cold-hearted, hateful seductress -- and Silas Lynch -- a power hungry, sex-obsessed criminal -- were early examples of the pathologies supposedly inherent in the tragic mulatto stereotype.

Mulattoes did not fare better in other books and movies, especially those who passed for white. In Nella Larsen's novel Passing (1929), Clare, a mulatto passing for white, frequently is drawn to black people in Harlem. Her bigoted white husband finds her there. Her problems are solved when she falls to her death from a sixth story window. In the movie Show Boat (Laemmle & Whale, 1936), a beautiful young entertainer, Julie, discovers that she has "Negro blood." Existing laws held that "one drop of Negro blood makes you a Negro." Her husband (and the movie's writers and producer) take this "one drop rule" literally. The husband cuts her hand with a knife and sucks her blood. This supposedly makes him a Negro. Afterward Julie and her newly-mulattoed husband walk hand-in-hand. Nevertheless, she is a screen mulatto, so the movie ends with this one-time cheerful "white" woman, now a Negro alcoholic.

Lost Boundaries is a book by William L. White (1948), made into a movie in 1949 (de Rochemont & Werker). It tells the story of a troubled mulatto couple, the Johnsons. The husband is a physician, but he cannot get a job in a southern black hospital because he "looks white," and no southern white hospital will hire him. The Johnsons move to New England and pass for white. They become pillars of their local community -- all the while terrified of being discredited. Years later, when their secret is discovered, the townspeople turn against them. The town's white minister delivers a sermon on racial tolerance which leads the locals, shamefaced and guilt-ridden, to befriend again the mulatto couple. Lost Boundaries, despite the white minister's sermon, blames the mulatto couple, not a racist culture, for the discrimination and personal conflicts faced by the Johnsons.

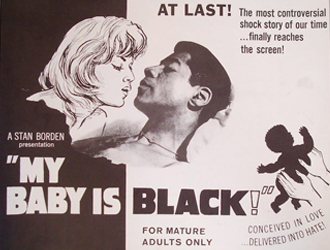

In 1958 Natalie Wood starred in Kings Go Forth (Ross & Daves), the story of a young French mulatto who passes for white. She becomes involved with two American soldiers on leave from World War II. They are both infatuated with her until they discover that her father is black. Both men desert her. She attempts suicide unsuccessfully. Given another chance to live, she turns her family's large home into a hostel for war orphans, "those just as deprived of love as herself" (Bogle, 1994, p. 192). At the movie's end, one of the soldiers is dead; the other, missing an arm, returns to the mulatto woman. They are comparable, both damaged, and it is implied that they will marry.

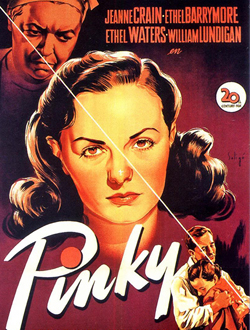

The mulatto women portrayed in Show Boat, Lost Boundaries, and Kings Go Forth were portrayed by white actresses. It was a common practice. Producers felt that white audiences would feel sympathy for a tortured white woman, even if she was portraying a mulatto character. The audience knew she was really white. In Pinky (Zanuck & Kazan, 1949), Jeanne Crain, a well-known actress, played the role of the troubled mulatto. Her dark-skinned grandmother was played by Ethel Waters. When audiences saw Ethel Waters doing menial labor, it was consistent with their understanding of a mammy's life, but when Jeanne Crain was shown washing other people's clothes audiences cried.

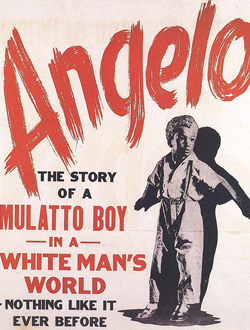

Even black filmmakers like Oscar Micheaux made movies with tragic mulattoes. Within Our Gates (Micheaux, 1920) tells the story of a mulatto woman who is hit by a car, menaced by a con man, nearly raped by a white man, and witnesses the lynching of her entire family. God's Step Children (Micheaux, 1938) tells the story of Naomi, a mulatto who leaves her black husband and child and passes for white. Later, consumed by guilt, she commits suicide. Mulatto actresses played these roles.

Fredi Washington, the star of Imitation of Life, was one of the first cinematic tragic mulattoes. She was followed by women like

Dorothy Dandridge and Nina Mae McKinney. Dandridge deserves special attention because

she not only portrayed doomed, unfulfilled women, but she was the embodiment of the

tragic mulatto in real life. Her role as the lead character in Carmen Jones (Preminger, 1954) helped make her a star. She was the first black featured on the

cover of Life magazine. In Island in the Sun (Zanuck & Rossen, 1957) she was the first black woman to be held -- lovingly -- in

the arms of a white man in an American movie. She was a beautiful and talented actress,

but Hollywood was not ready for a black leading lady; the only roles offered to her

were variants of the tragic mulatto theme. Her personal life was filled with failed

relationships. Disillusioned by roles that limited her to exotic, self-destructive

mulatto types, she went to Europe, where she fared worse. She died in 1965, at the

age of forty-two, from an overdose of anti-depressants.

Fredi Washington, the star of Imitation of Life, was one of the first cinematic tragic mulattoes. She was followed by women like

Dorothy Dandridge and Nina Mae McKinney. Dandridge deserves special attention because

she not only portrayed doomed, unfulfilled women, but she was the embodiment of the

tragic mulatto in real life. Her role as the lead character in Carmen Jones (Preminger, 1954) helped make her a star. She was the first black featured on the

cover of Life magazine. In Island in the Sun (Zanuck & Rossen, 1957) she was the first black woman to be held -- lovingly -- in

the arms of a white man in an American movie. She was a beautiful and talented actress,

but Hollywood was not ready for a black leading lady; the only roles offered to her

were variants of the tragic mulatto theme. Her personal life was filled with failed

relationships. Disillusioned by roles that limited her to exotic, self-destructive

mulatto types, she went to Europe, where she fared worse. She died in 1965, at the

age of forty-two, from an overdose of anti-depressants.

Today's successful mulatto actresses -- for example, Halle Berry, Lisa Bonet and Jasmine Guy -- owe a debt to the pioneering efforts of Dandridge. These women have great wealth and fame. They are bi-racial, but their statuses and circumstances are not tragic. They are not marginalized; they are mainstream celebrities. Dark-skinned actress -- Whoopi Goldberg, Angela Bassett, Alfre Woodard, and Joie Lee -- have enjoyed comparable success. They, too, benefit from Dandridge's path clearing.

The tragic mulatto was more myth than reality; Dandridge was an exception. The mulatto was made tragic in the minds of white people who reasoned that the greatest tragedy was to be near-white: so close, yet a racial gulf away. The near-white was to be pitied -- and shunned. There were undoubtedly light skinned black people, male and female, who felt marginalized in this race conscious culture. This was true for many people of color, including dark skinned black people. Self-hatred and intraracial hatred are not limited to light skinned black people. There is evidence that all racial minorities in the United States have battled feelings of inferiority and in-group animosity; those are, unfortunately, the costs of being a minority.

The tragic mulatto stereotype claims that mulattoes occupy the margins of two worlds, fitting into neither, accepted by neither. This is not true of real life mulattoes. Historically, mulattoes were not only accepted into the black community, but were often its leaders and spokespersons, both nationally and at neighborhood levels. Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. DuBois, Booker T. Washington, Elizabeth Ross Hayes,2 Mary Church Terrell,3 Thurgood Marshall, Malcolm X, and Louis Farrakhan were all mulattoes. Walter White, the former head of the NAACP, and Adam Clayton Powell, an outspoken Congressman, were both light enough to pass for white. Other notable mulattoes include Langston Hughes, Billie Holiday, and Jean Toomer, author of Cane (1923), and the grandson of mulatto Reconstruction politician P.B.S. Pinchback.

There was tragedy in the lives of light skinned black women -- there was also tragedy in the lives of most dark skinned black women -- and men and children. The tragedy was not that they were black, or had a drop of "Negro blood," although white people saw that as a tragedy. Rather, the real tragedy was the way race was used to limit the chances of people of color. The 21st century finds an America increasingly more tolerant of interracial unions and the resulting offspring.

© Dr. David Pilgrim, Professor of Sociology

Ferris State University

Nov., 2000

Edited 2024

1 A mulatto is defined as: the first general offspring of a black and white parent; or, an individual with both white and black ancestors. Generally, mulattoes are light-skinned, though dark enough to be excluded from the white race.

2 Elizabeth Ross Hayes was a social worker, sociologist, and a pioneer in the YWCA movement.

3 Mary Church Terrell was a feminist, civil rights activist, and the first president of the National Association of Colored Women.

Barnes, G. (1932). Dark lustre. New York, NY: A. H. King.

Bogle. D. (1994). Toms, coons, mulattoes, mammies, & bucks: An interpretive history of Blacks in American films. New York, NY: Continuum.

Brown, S. (1969). Negro poetry and drama and the Negro in American fiction. New York, NY: Atheneum.

Brown, W. W. (1853). Clotel, or, The President's daughter: a narrative of slave life in the United States. London: Partridge & Oakley.

Carroll, C. (1900). "The Negro a beast"; or, "In the image of God". St. Louis, MO: American Book and Bible House.

Caspary, V. (1929). The white girl. New York, NY: J. H. Sears & Co.

De Rochemont, L. (Producer), & Werker, A. L. (Director). (1949). Lost boundaries [Motion picture]. United States: Louis De Rochemont Associates.

Dixon, T. (1905). The clansman: an historical romance of the Ku Klux Klan. New York, NY: Grosset & Dunlap.

Fredrickson, G. M. (1971). The Black Image in the White Mind: The Debate on Afro-American Character and Destiny 1817-1914. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Furnas, J. C. (1956). Goodbye to Uncle Tom. New York, NY: Apollo, 1956.

Griffith, D.W. (Producer/Director) (1915). The birth of a nation [Motion picture]. United States: David W. Griffith Corp.

Hunter, R. (Producer), & Sirk, D. (Director). (1959). Imitation of life [Motion picture]. United States: Universal International Pictures.

Hurst. F. (1933). Imitation of life, a novel. New York, NY: Harper & Bros.

Jewison, N. (Producer/Director). (1984). A soldier's story [Motion picture]. United States: Columbia Pictures Corporation.

Laemmle, C. Jr. (Producer), & Stahl, J. M. (Director). (1934). Imitation of life [Motion picture]. United States: Universal Pictures.

Laemmle, C. Jr. (Producer), & Whale, J. (Director). (1936). Show boat [Motion picture]. United States: Universal Pictures.

Larsen, N. (1929). Passing. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Leab, D. (1976). From Sambo to Superspade: The black experience in motion pictures. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Micheaux, O. (Producer/Director). (1938). God's step children [Motion picture]. United States: Micheaux Film.

Micheaux, O. (Producer/Director). (1920). Within our gates [Motion picture]. United States: Micheaux Book & Film Company.

Nash, G. B. (1974). Red, white, and black: The peoples of early America. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Preminger, O. (Producer/Director). (1954). Carmen Jones [Motion picture]. United States: Carlyle Productions.

Reuter, E. B. (1918). The mulatto in the United States. Boston, MA: Badger.

Ross, F. (Producer), & Daves, D. (Director). (1958). Kings go forth [Motion picture]. United States: Frank Ross-Eton Productions.

Toomer, J. (1923). Cane. New York, NY: Boni and Liveright.

White, W. L. (1948). Lost boundaries. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace.

Zanuck, D. F. (Producer), & Kazan, E. (Director). (1949). Pinky [Motion picture]. United States: Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation.

Zanuck, D. F. (Producer), & Rossen, R. (Director). (1957). Island in the sun [Motion picture]. United States: Darryl F. Zanuck Productions.