Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

Jefferson Parish deputies practice marksmanship by shooting paintballs at this handmade wooden target. Experts say that the image fits into a long American tradition of using images of blacks as targets -- and fear it will lead to more blacks being targeted on the streets.

By Katy Reckdahl

As she stood behind the Jefferson Parish Correctional Center last summer, the young filmmaker saw a homemade wooden target, its face painted with extra-large white eyes and big red lips.

She remembers trying to find an excuse for it. "I thought, maybe it was old and they were just throwing it out," she says. "Maybe it wasn't used anymore. Or maybe there was some other explanation that would make it less disturbing." Curious, she and her crew walked closer to film it and take some photographs.

By a strange coincidence, the filmmaker was Emily Kunstler, daughter of renowned civil rights attorney William Kunstler. "We grew up in a household that was very conscious of race and injustice," says Emily's sister and fellow filmmaker, Sarah Kunstler. Their late father had worked closely with many black leaders, including the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., whom Kunstler had met with at the Lorraine Motel the night before the civil rights leader's assassination. Over the years, he'd defended free speech and racial equality in many high-profile cases, with a client list that included Malcolm X, jailed Freedom Riders in Mississippi, rioting prisoners in Attica, and American Indian Movement leader Russell Means.

With their production company, Off Center Productions, the Kunstler sisters are continuing their father's advocacy but through a different path -- film. The Road to Justice, Off Center's current project, a collaborative effort with producer Julia Phillips, traces the wrongful conviction of a Jefferson Parish youth Ryan Matthews. By the time DNA evidence prompted Matthews' release last fall, they'd shot 100 hours of footage about the young man, who spent seven years in prison, most of them on Louisiana's death row.

Emily Kunstler stumbled onto the target last summer after attending a court hearing for Matthews, who that day had gotten one step closer to release. She was in a celebratory mood, she says, as she, Phillips and their cinematographer filmed the short walk from the Gretna courthouse to the Jefferson Parish Correctional Center. But, the Kunstlers say, the crudely made wooden target gave them a wake-up call -- a grim glimpse into how black defendants are viewed in Jefferson Parish.

"You practice using them as targets," says Sarah Kunstler, "and then, the implication is, you target them in real life."

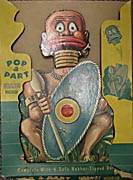

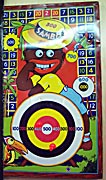

Racist target imagery through the years include a circa -1940s "Ubangi Warrior Pop-Up" game in which the warrior's head popped off when hit by suction darts, a circa-1940s "Sambo" game board that came with a toy pistol, a metal target used in the 1960s for practice in Kentucky before the Jim Crow Museum purchased it off eBay in 2003 (and which can still be found on white- power Web sites), and a photo target that is currently popular at gun shows.

Courtesy of the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Imagery

UNTIL LAST WEEK, Jefferson Parish Sheriff Harry Lee hadn't personally seen the wooden target. After being asked about it by Gambit Weekly, he ordered his deputies to haul the target over to his office.

He soon called back. "I'm looking at this thing that people say is offensive," he says. "I've looked at it, I don't find it offensive, and I have no interest in correcting it."

According to law-enforcement standards, the target is a little unconventional. Most law enforcement agencies, including the New Orleans Police Department, practice marksmanship on standard torso silhouettes, often colored black but sometimes green or purple.

According to Lee, his deputies -- who have to be qualified annually with their weapons -- built the target four years ago for hands-on training. They most often use paintballs the same size as standard-issue pepper balls, which contain pepper spray and are shot by Jeff Parish deputies to incapacitate suspects without using lethal force. All in all, the sheriff's department incurs very few expenses -- because the paintballs are inexpensive and so is the target, which they can just use and hose off.

Lee stands back to describe what he's seeing. "It's just a homemade thing," he says. The image that's worn overall, but is especially shot up in the middle of the chest, because that's where deputies aim. Its creators were also sparing with paint, he says, only applying it for eyes, lips and an orange prison jumpsuit.

"A critic could say that the painting is not representative of a Caucasian eye or a Caucasian mouth, but it doesn't look much like an African mouth either," said Lee. In fact, it could even be "a Chinaman," says the sheriff, who is Chinese. "No, wait," he says, "the eyes aren't slanted enough to be a Chinaman." That gets a big laugh from the deputies in his office.

One thing is clear -- this is no racist caricature, says Lee. "Everybody has red lips. You have red lips and I have red lips. It has two eyeballs, just two eyes." The plywood was black simply because it was a piece of 10-year-old wood that had been sitting outside for several years, getting darker. "So blame God, not me," he said.

The response is vintage Sheriff Harry Lee, who during his 25-year tenure has not shied away from controversy when it comes to questions about race. During the 1980s, Lee had ordered special scrutiny for any black people traveling in white sections of the parish. "It's obvious," he had said, "that two young blacks driving a rinky-dink car in a predominantly white neighborhood they'll be stopped." He later apologized for the comment.

In 1994, after two black men died in the Jefferson Parish Correctional Center within one week, Lee faced protests from the black community and responded by withdrawing his officers from a predominantly black neighborhood. "To hell with them," he'd said. "I haven't heard one word of support from one black person." He soon returned his officers to their regular patrol.

But as for the target, Lee had no apologies. When told that some black deputies, interviewed by Gambit, had grimaced about the target's design, Lee still didn't budge. "If anyone thinks it's a black person, that's the most ludicrous thing I've heard," he said.

The phone rang again about 30 minutes later. "This is Harry Lee again. I just talked to someone else about that silhouette." He chuckled. "And it was pointed out to me that blacks don't have red lips; blacks have brown lips. White people have red lips."

PUT A PHOTO OF THAT wooden target in front of museum curator David Pilgrim and he calls it a racist caricature -- immediately. "It's your typical Sambo or coon image," says Pilgrim, the founder of the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Imagery, a Michigan-based collection that houses more than 4,000 racist artifacts.

The wooden target would fit nicely into the museum's new building, he says, which will devote an entire room to what he calls "this country's long and sad history of using blacks as targets."

The Jefferson Parish target, he says, is rooted in games like "Hit the Coon" or "African Dodger," which were popular on fairgrounds and traveling carnival shows during the late 1800s. The game's operators usually set up an elaborately painted canvas, most often depicting a plantation scene. "Then a black man would stick his head through this canvas," Pilgrim explains, "and white patrons would throw balls, or even rocks, at the man's head to win prizes." Eventually, the game evolved so that the men would be wearing protective helmets covered with curly hair. Some manufacturers also created life-size "Negro Heads" made of wood, since it wasn't always easy to find live targets.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, the idea of using blacks as targets became more mainstream. "You'd be hard-pressed to name a major toy manufacturer that did not have some game at some point where you threw at blacks," Pilgrim says. There were games of ring-toss, bean-bag toss and bowling. There was "Hit Me Hard," where players threw wooden balls through a child's big smile and "Chuck," a game where contestants threw little watermelon-shaped discs into a kid's mouth.

Backyard pursuits mimicked what was on the market. "Deer hunters and other hunters, the targets they created for themselves often had black imagery on them," says Pilgrim.

At certain times, Pilgrim notes, children's games also caricatured Native Americans and different immigrant groups -- namely Italians, Irish, Chinese and Mexicans. "But there's been no group with as many variations as blacks. And no other group where the images have continued to the present this way," says Pilgrim.

Even today, rifle targets picturing blacks are not hard to find, he says. A few years ago, he went to a gun show in Michigan and asked a dealer for his most popular paper target. At first, the dealer looked up, saw Pilgrim was not white, and balked. Then, after Pilgrim talked with him, the dealer pulled out a target of a young black man, wearing a backward baseball cap, low-slung pants and a scowl.

"Is this your most popular target?" Pilgrim asked. "Yeah, by far," said the dealer.

The Internet is also filled with free, downloadable paper targets of squirrels, deer, grizzly bears, and images of Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein with bull's-eyes on their faces. There's been a resurgence in a downloadable image usually titled the "Runnin' Nigger Target," a silhouette of a sprinting man with a big Afro that has been circulating among certain groups since the 1960s. Today, it can be found on the Internet on a number of different white-power sites, sometimes showing up on a background of Confederate flags.

This particular target has been named in a few different lawsuits by African-American officers whose colleagues either used the target for practice or, in a St. Mary Parish case, sent the image as an email message to all members of the police department. The silhouette is often accompanied by captions like "Warning: bullets may ricochet when aiming at head" and "8-point bonus for head shot using armor-piercing ammo."

Vintage black target games are also still sold in flea markets, antique shops and on eBay, which typically has a large selection in its "black Americana" section. Pilgrim logs on to see what's there. He finds a "Jolly Little Darkie Game," where players throw a sack into the mouth of a black person, and a 1915 game called the Baby Rack, where contestants use a toy cannon to shoot at caricatured black babies made of tin.

Targets with babies on them -- the thought is obviously disturbing to Pilgrim. He takes a deep breath. "If all you knew about race relations was what you saw in these games, what would you think of white people's attitudes toward blacks?" he asks.

AROUND MIDNIGHT on a February evening in 1999, New York police officers saw Amadou Diallo, a 22-year-old West African immigrant standing in a doorway in the Bronx. They ordered him not to move and he reached for his pants pocket, prompting them to fire a total of 41 shots, 19 of which hit Diallo. What officers couldn't see was that Diallo had reached for nothing more than his wallet.

His death and others like it have sparked community protests and outrage. It also inspired more academic interest in research that tests the effects of race on shoot/don't shoot decisions.

Graduate student Joshua Correl and his colleagues at the University of Colorado at Boulder created photos of African-American and white targets, either holding two different guns or harmless objects such as a silver-colored Coke can, a silver camera, a black cell phone and a black wallet. Using a videogame, participants were instructed to shoot armed targets and to say "Don't shoot" for any unarmed targets. The study showed what Correl calls "a pattern of bias." Specifically, white participants shot an armed target more quickly if he was an African American and decided to "not shoot" more quickly when the target was white.

Correl explains what he would tell a participant with those results. "It's not that you want bad things for black people," he says. "But whether you endorse it personally or not, you have an association between the idea of black people and the idea of danger. And when you see a black person, for just a split second, the idea of danger pops to mind -- that prompts you to respond as if the target is a threat."

The University of Colorado study is titled "The Police Officer's Dilemma," even though the study's participants were often college students and people in the community. That's because these types of studies have special meaning for law-enforcement officers. "They're one of the few professions where split-second decisions may potentially be influenced by stereotypes," says Correl, noting that a team of researchers at Florida State University recently recruited police officers to participate in a similar study. Colorado's results were basically paralleled in Florida -- officers were more likely to shoot unarmed black suspects as compared with unarmed white suspects.

Those conclusions also mirror what Professor Anthony Greenwald found with a study he directed recently at the University of Washington, using college students as participants. Greenwald is not surprised that the findings match up. "We believe that police, like other people, don't realize the way that their minds work unconsciously."

The research does, perhaps, carry more significance for police officers because they need to take extra steps in training to make sure that police are aware of what Greenwald's study terms "automatic responses" -- reactions to the way that people's minds work unconsciously.

The National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives (NOBLE) addressed this issue in a 2001 report, which concludes that Diallo's death was the result of bias-based policing. The report notes that some law enforcement agencies address this issue by beefing up their firearm training. "This response would be effective if the nature of the problem were shooting skills," says the report. "But the nature of the problem is bias. Otherwise, these types of shootings would not predominately affect minority officers and suspects."

Greenwald currently oversees a Web site (Implicit.harvard.edu) where anyone can self-test biases by logging on and choosing the race-weapons test. Of the 30,000 to 40,000 people who have taken this test online, about 80 percent associate weapons more with blacks than whites. "African Americans show this bias themselves," says Greenwald. "This bias is much less than that of whites or Asians -- but it's still a bias." There's a lesson here for Jefferson Parish, says Greenwald. Officers who practice repeatedly with black targets -- or targets perceived to be black -- may be re-enforcing already-existing biases and stereotypes. "Practices like that do nothing to reverse automatic associations -- they only strengthen them," says Greenwald.