Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

The Golliwog (originally spelled Golliwogg) is the least known of the major anti-black caricatures in the United States. Golliwogs are grotesque creatures,1 with very dark, often jet black skin, large white-rimmed eyes, red or white clown lips, and wild, frizzy hair.2 Typically, it's a male dressed in a jacket, trousers, bow tie, and stand-up collar in a combination of red, white, blue, and occasionally yellow colors. The golliwog image, popular in England and other European countries, is found on a variety of items, including postcards, jam jars, paperweights, brooches, wallets, perfume bottles, wooden puzzles, sheet music, wall paper, pottery, jewelry, greeting cards, clocks, and dolls. For the past four decades Europeans have debated whether the Golliwog is a lovable icon or a racist symbol.

The Golliwog began life as a story book character created by Florence Kate Upton. Upton was born in 1873 in Flushing, New York, to English parents who had emigrated to the United States in 1870. She was the second of four children. When Upton was fourteen, her father died and, shortly thereafter, the family returned to England. For several years she honed her skills as an artist. Unable to afford art school, Upton illustrated her own children's book in the hope of raising tuition money.

In 1895, her book, entitled The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls, was published in London. Upton drew the illustrations, and her mother, Bertha Upton, wrote the accompanying verse. The book's main characters were two Dutch dolls, Peg and Sarah Jane, and the Golliwogg. The story begins with Peg and Sara Jane, on the loose in a toy shop, encountering "a horrid sight, the blackest gnome." The little black "gnome" wore bright red trousers, a red bow tie on a high collared white shirt, and a blue swallow-tailed coat. He was a caricature of American black faced minstrels -- in effect, the caricature of a caricature. She named him Golliwogg.

The Golliwogg was based on a Black minstrel doll that Upton had played with as a small child in New York. The then-nameless "Negro minstrel doll" was treated roughly by the Upton children. Upton reminiscenced: "Seated upon a flowerpot in the garden, his kindly face was a target for rubber balls..., the game being to knock him over backwards. It pains me now to think of those little rag legs flying ignominiously over his head, yet that was a long time ago, and before he had become a personality.... We knew he was ugly!" (Johnson).

Upton's Golliwogg character, like the rag doll which inspired it, was ugly. He was often drawn with paws instead of hands and feet. He had a coal black face, thick lips, wide eyes, and a mass of long unruly hair.3 He was a cross between a dwarf-sized black minstrel and an animal. The appearance was distorted and frightening (MacGregor, p. 125).

Florence Upton's ugly little creation was embraced by the English public. The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls was immensely popular in England, and Golliwogg became a national star. The second printing of the book was retitled The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls and a Golliwogg. For the next fourteen years, Bertha and Florence Upton created twelve more books featuring the Golliwogg and his adventures, traveling to such "exotic" places as Africa and the North Pole, accompanied by his friends, the Dutch Dolls ("Golliwog History", n.d.). In those books the Uptons put the Golliwogg first in every title.

The Uptons did not copyright the Golliwogg, and the image entered into public domain. The Golliwogg name was changed to Golliwog, and he became a common toyland character in children's books. The Upton Golliwogg was adventurous and sometimes silly, but, in the main, gallant and "lovable," albeit, unsightly. Later Golliwogs were often unkind, mean-spirited, and even more visually hideous.

The earliest Golliwog dolls were rag dolls made by parents for their children. Many thousands were made. During the early twentieth century, many prominent doll manufacturers began producing Golliwog dolls. The major Golliwog producers were Steiff, Schuco, and Levin, all three Germany companies, and Merrythought and Deans, both from Great Britain. The Steiff Company is the most notable maker of Golliwog dolls. In 1908 Steiff became the first company to mass produce and distribute Golliwog dolls. Today, these early Steiff dolls sell for $10,000 to $15,000 each, making them the most expensive Golliwog collectibles. Some Steiff Golliwogs have been especially offensive, for example, in the 1970s they produced a Golliwog who looked like a wooly haired gorilla. In 1995, on the 100th anniversary of the Golliwog creation, Steiff produced two Golliwog dolls, including the company's first girl Golliwog.

James Robertson & Sons, a British manufacturer of jams and preserves, began using the Golliwog as its trademark in the early 1900s. According to the company's promotional literature, it was in the United States, just before World War I, that John Robertson (the owner's son) first encountered the Golly doll. He saw rural children playing with little black rag dolls with white eyes. The children's mothers made the dolls from discarded black skirts and blouses. John Robertson claimed that the children called the dolls "Golly" as a mispronunciation of "Dolly." He returned to England with the Golly name and image.

By 1910 the Golly appeared on Robertson's product labels, price lists, and advertising material. Its appeal led to an enormously popular mail-away campaign: in return for coupons from their marmalade, Robertson's sent brooches (also called pins or badges) of Gollies playing various sports. The first brooch was the Golly Golfer in 1928 ("Gollies Through History," n.d.). In 1932 a series of fruit badges (with Golly heads superimposed onto the berries) were distributed. In 1939 the popular brooch series was discontinued because the metal was needed for the war effort,4 but by 1946 the Golly returned. In 1999 a Robertson spokesperson said, "He's still very popular. Each year we get more than 340,000 requests for Golly badges. Since 1910 we have sent out more than 20 million" (Clark). The Robertson Golly has also appeared on pencils, knitting patterns, playing cards, aprons, and children's silverware sets.

Robertson pendant chains were introduced in 1956, and, soon after, the design of all Robertson Gollies changed from the Old Golly with pop eyes to the present Golly with eyes looking to the left. The words "Golden Shred" were removed from his waistcoat, his eyes were straightened, and his smile was broadened ("And There's Even More: history", n.d.).

During the first half of the twentieth century, the Golliwog doll was a favorite children's soft toy in Europe. Only the Teddy Bear exceeded the Golliwog in popularity. Small children slept with their black dolls. Many white Europeans still speak with nostalgic sentiment about their childhood gollies. Sir Kenneth Clark, the noted art historian, claimed that the Golliwogs of his childhood were, "examples of chivalry, far more persuasive than the unconvincing Knights of the Arthurian legend" (Johnson, n.d., p. 3). The French composer Claude Debussy was so enthralled by the Golliwogs in his daughter's books that one movement of his Children's Corner Suite is entitled "The Golliwog's Cakewalk" (Johnson, n.d., p. 3). The Golliwog was a mixture of bravery, adventurousness, and love -- for white children.

In the 1960s relations between black and white people in England were often characterized by conflict. This racial antagonism resulted from many factors, including: the arrival of increasing numbers of colored immigrants; minorities' unwillingness to accommodate themselves to old patterns of racial and ethnic subordination; and, the fear among many white people that England was losing its national character. British culture was also influenced by images -- often brutal -- of racial conflict occurring in the United States.

In this climate the Golliwog doll and other Golliwog emblems were seen as symbols of racial insensitivity. Many books containing Golliwogs were withdrawn from public libraries, and the manufacturing of Golliwog dolls dwindled as the demand for Golliwogs decreased. Many items with Golliwog images were destroyed. Despite much criticism, James Robertson & Sons did not discontinue its use of the Golliwog as a mascot. The Camden Committee for Community Relations led a petition drive for signatures to send to the Robertson Company. The National Committee on Racism in Children's Books also publicly criticized Robertson's use of the Golly in its advertising. Other organizations called for a boycott of Robertson's products; nevertheless, the company has continued to use the Golliwog as its trademark in many countries, including the United Kingdom, although it was removed from Robertson's packaging in the United States, Canada, and Hong Kong.

In many ways the campaign to ban Golliwogs was similar to the American campaign against Little Black Sambo. In both cases racial minorities and sympathetic white people argued that these images demeaned black people and hurt the psyches of minority children. Civil rights organizations led both campaigns, and white civic and political leaders eventually joined the effort to ban the offensive caricatures. In the anti-Golliwog campaign, numerous British parliamentarians publicly lambasted the Golliwog image as racist, including, Tony Benn, Shirley Williams, and David Owen (MacGregor, 1992, p. 29).

The claim that Golliwogs are racist is supported by literary depictions by writers such as Enid Blyton. Unlike Florence Upton's, Blyton's Golliwogs were often rude, mischievous, elfin villains. In Blyton's book, Here Comes Noddy Again (1951), a Golliwog asks the hero for help, then steals his car. Blyton, one of the most prolific European writers, included the Golliwogs in many stories, but she only wrote three books primarily about Golliwogs: The Three Golliwogs (1944), The Proud Golliwog (1951), and The Golliwog Grumbled (1955). Her depictions of Golliwogs are, by contemporary standards, racially insensitive. An excerpt from The Three Golliwogs is illustrative:

Once the three bold golliwogs, Golly, Woggie, and Nigger, decided to go for a walk to Bumble-Bee Common. Golly wasn't quite ready so Woggie and Nigger said they would start off without him, and Golly would catch them up as soon as he could. So off went Woogie and Nigger, arm-in-arm, singing merrily their favourite song -- which, as you may guess, was Ten Little Nigger Boys.(p. 51)

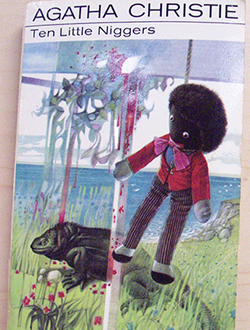

Ten Little Niggers is the name of a children's poem, sometimes set to music, which celebrates the deaths of ten Black children, one-by-one. The Three Golliwogs was reprinted as recently as 1968, and it still contained the above passage. Ten Little Niggers5 was also the name of a 1939 Agatha Christie novel, whose cover showed a Golliwog lynched, hanging from a noose.

The Golliwog's reputation and popularity were also hurt by the association with the word wog. Apparently derived from the word Golliwog,6 wog is an English slur against dark-skinned people, especially Middle or Far East foreigners. During World War II the word wog was used by the British Army in North Africa, mainly as a slur against dark-skinned Arabs. In the 1960s the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, one of the most noted regiments in the British Army, wore a Robertson's golly brooch for each Arab they had killed ("And There's Even More: Golly", n.d.) After the war, wog became a more general slur against brown-skinned people. As a racial epithet, it is comparable to nigger or spic, though its usage extends beyond any single ethnic group. Dark-skinned people in England, Germany, and Australia are derisively called wogs.7 In the year 2000, a British police officer was fired for referring to an Asian colleague as a wog ("British policeman", 2000). The association of wog with racial minorities is also seen with the word wog-box, which is slang for a large portable music box, the European counterpart of the ghetto blaster. The wog-box is also called a "Third World briefcase" (Green, 1984, p. 309).

Some Golliwog supporters tried to distance themselves from the wog slur by dropping it from the word golliwog. James Robertson & Sons, for example, has always referred to its golliwog as "Golly." In the late 1980s, when the anti-Golliwog campaign reached its height, many small manufacturers of the golliwogs began using the names Golly or Golli, instead of Golliwog. Not surprisingly, the words Golliwog, Golly, and Golli are now all used as racially descriptive terms, although they are not as demeaning as wog.

Golliwog is a racial slur in Germany, England, Ireland, Greece, and Australia. Interestingly, it is sometimes applied to dark-skinned white people, as well as brown-skinned persons. Golliwog is also a common name for black pets, especially dogs, in European countries -- much as nigger was once popular as a pet name. Golliwog was also the original name of the rock band Credence Clearwater Revival. They sometimes performed the song "Brown-Eyed Girl" (not the Van Morrison tune), dressed in white afros. This is not to suggest that they were racists, only to show that golliwogs were a part -- albeit, a small one -- in American culture ("Brief History", n.d.).

The Golliwog celebrated its 100 year anniversary in 1995. Golliwog collectibles, which always had a loyal following, again boomed on the secondary market. This popularity continues today and is evidenced by numerous eBay and Yahoo internet auctions and the presence of several international Golliwog organizations. A pro-Golliwog viewpoint can be found at the International Golliwog Collectors Club's website at www.teddybears.com/golliwog/direct.html. Many collectors, primarily though not exclusively white people, contend that the anti-Golliwog movement represents political correctness at its worst. They argue that the Golliwog is just a doll, and that the original Florence Upton creation was not racist, intentionally or unintentionally -- this is reminiscent of the claims about Helen Bannerman's Little Black Sambo (Read the Picaninny Caricature essay on this website for a more in-depth discussion of Little Black Sambo).

Critics of the Golliwog have launched a new attack. They are trying to get the image removed from all newly published children's books, and they are trying to force businesses to not use the Golliwog as a trademark. The black Trinidadian writer, Darcus Howe, said, "English [white] people never give up. Golliwogs have gone and should stay gone. They appeal to White English sentiment and will do so until the end of time." Gerry German, of the Working Group Against Racism in Children's Resources, was quoted in The Voice, a black newspaper, as saying: "I find it appalling that any organization in this day and age can produce anything which would commemorate the golliwog. It is an offensive caricature of Black people" (Clark, 1999).

The Golliwog was created during a racist era. He was drawn as a caricature of a minstrel

-- which itself represented a demeaning image of black people. There is racial stereotyping

of black people in Florence Upton's books, including The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls -- such as the black minstrel playing a banjo on page 45. It appears that the Golliwog

was another expression of Upton's racial insensitivity. Certainly later Golliwogs

often reflected negative beliefs about black people -- thieves, miscreants, incompetents.

There is little doubt that the words associated with Golliwog -- Golly, Golli, Wog,

and Golliwog, itself -- are often used as racial slurs. Finally, the resurgence of

interest in the Golliwog is not found primarily among children, but instead is found

among adults, some nostalgic, others with financial interests.

The Golliwog was created during a racist era. He was drawn as a caricature of a minstrel

-- which itself represented a demeaning image of black people. There is racial stereotyping

of black people in Florence Upton's books, including The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls -- such as the black minstrel playing a banjo on page 45. It appears that the Golliwog

was another expression of Upton's racial insensitivity. Certainly later Golliwogs

often reflected negative beliefs about black people -- thieves, miscreants, incompetents.

There is little doubt that the words associated with Golliwog -- Golly, Golli, Wog,

and Golliwog, itself -- are often used as racial slurs. Finally, the resurgence of

interest in the Golliwog is not found primarily among children, but instead is found

among adults, some nostalgic, others with financial interests.

© Dr. David Pilgrim, Professor of Sociology

Ferris State University

Nov., 2000

Edited 2012

1 The adjective grotesque reflects, of course, a subjective judgement; however, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (2011) defines Golliwog as a "doll fashioned in grotesque caricature of a black male."

2 Langenscheidt's New College German Dictionary (Brough & Messinger, 1995, p. 283) has this citation for golliwog: gol-li-wog (g) 1. gro'teske schwarze Puppe; 2. fig. Vogelscheuche' f (Person). The English translation is: 1. grotesque black doll; 2. fig. scarecrow' (person). Thanks to Maryanne Heidemann for translating the definition.

3This description is taken from MacGregor (1992, p. 124). MacGregor is one of the few scholars to offer a thorough examination of Golliwogs.

4Florence Upton donated her original Golliwoggs drawings for public auction to support the WW II British war effort.

5 The name was later changed to Ten Little Indians, then later to And Then There Were None. All of the books are still readily available on the secondary market.

6There is some speculation that wog is an acronym for one of the following: Western Oriental Gentleman, Worthy Oriental Gentleman, Wily Oriental Gentleman, Wonderful Oriental Gentleman, or Working On Government Service. The numerous variations and a lack of supporting evidence suggest that wog was not an acronym. See Wilton (2007).

7 Wog is also slang for non-Brits, and is used against the French and even the Danish. It is sometimes employed with a smug, patronizing tone of voice, rather than the snarl which usually accompanies the use of nigger, spic, and other racial ethnophaulisms. Wog is both an ethnic slur and a racial epithet.

The American heritage dictionary of the English language (2011). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Retrieved from http://ahdictionary.com/.

And there's even more: Golly is not politically correct (n.d.). Golly Corner Website. Retrieved from http://www.gollycorner.co.uk/.

And there's even more: The history of Golly (n.d.). Golly Corner Website. Retrieved from http://www.gollycorner.co.uk/.

Blyton, E. (1955). The golliwog grumbled. Leicester, England: Brockhampton Press.

Blyton, E. (1951). Here comes Noddy again. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co., Ltd.

Blyton, E. (1951). The proud golliwog. Leicester, England: Brockhampton Press.

Blyton, E. (1944). The three golliwogs. London: George Newnes.

A brief history of CCR. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://home1.swipnet.se/~w-17068/sida4.htm.

British policeman fired for racist remark in landmark case (2000, July 4). The Times of India.

Brough, S. & Messinger, H. (1995). Langenscheidt's new college German dictionary. New York, NY: Langenscheidt.

Christie, A. (1939). Ten little niggers. London: Collins.

Clark, J. (1999, June 22). A sticky end at last for Golly? Daily Mail.

Gollies through history. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.angelfire.com/wi/golly/aghist.htm.

Golliwog history. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.golliwogg.co.uk/history.htm.

Green, J. (1984). The dictionary of contemporary slang. New York, NY: Stein and Day, 1984.

Johnson, D. B. (n.d.). Nabokov's Golliwogs: Lodi reads English 1899-1909. Retrieved from http://www.libraries.psu.edu/nabokov/dbjgo1.htm.

MacGregor, R. M. (1992). The Golliwog: Innocent doll to symbol of racism. In Danna, S. R. (Ed.), Advertising and popular culture: Studies in variety and versatility. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press.

Upton, B., & Upton, F. K. (1895). The adventures of two Dutch dolls and a Golliwog. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

Wilton, D. (2007, February 24). Wog. Wordorigins.org. Retrieved from http://www.wordorigins.org/index.php/more/579.