Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

The rooster crows tomorrow at 6:33, and I have been looking for civility for a long time.

On the playground the children chanted: "U-G-L-Y. You don't have an alibi. You're ugly, yeah, yeah, you're ugly." A seven year old claimed that "pimping ain't easy." I was looking for civility but I found children who told their parents to shut up—and parents who shut up. School children who played hide-and-go-seek with real killers, boogey men with guns, and journalists who stuck microphones near the faces of grieving mothers and asked, "How does it feel to lose your daughter? Tell our viewers how it feels."

Like Jeremiah from the Old Testament I desperately needed to find righteous people.

A man in the airport, my brother born of different parents, wore a shirt that read, "Don't make me pull an O.J. on you." I told him to take it off; it gives offense. He said, "Mind your own business!" I said, "It is my business, Brother." He said, "Shut up!" I said, "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere." From his mouth came an F Train: "You flipping, flying, freaking, faking, frigging, flakey..." or something like that. The airport security guard told me that I "talk funny" and “leave that man alone.”

I went looking for civility.

A student belched loud and long, like a horn announcing the arrival of royalty, coarse and vulgar, like the frat boys at Animal House. From the back of the room a voice yelled, "Good one," and the class erupted in laughter. I have students who come to class late, with cell phones ringing, no books, no pencils, leaving warm beds to sleep in my class, demanding, asserting their right to not know, not sacrifice, not commune, demanding their customers' rights, legs open, minds closed, lips profane, leaving early. Rudeness is a lack of respect for others. It is selfishness and the man in my mirror is victim and offender.

I went looking for civility.

I found supervisors who walk out during employee's presentations and office managers who find their perfect love with pink slips. And, workers who steal time, steal product, and curse their supervisors in public spaces. Everywhere there is anger, disgust, folks nursing a bitter pill—and everywhere the chorus: "What about me? What about mine?"

It is easy to see incivility in others.

At D&W an elderly man picked his nose, a teenager talked on her cell phone, a woman cut in line, and a boy made a sandwich with the store's food. At the office, a man with bad breath, Marlboros and coffee, wanted to tell me a secret: gossip that tears down—and, alas, I gave him an audience—another explained why he hasn’t spoken to several colleagues since 2013. At church, the preacher reminisced that he grew up in a family without Christians—a Catholic aunt and uncle—but no Christians. A colleague forwarded "blonde jokes." The doctor was late for an appointment he made. On a television talk show guests fought, cursed, and degraded themselves, their families and us for their 15 minutes of fame/infamy. I watched.

Political elites use incivility to rile audiences, to remind them whom to hate, red meat for their base. For years I told audiences that the United States is more egalitarian, more democratic than it has ever been. I stopped saying that three years ago. The rhetoric that I hear today—especially when race is involved—sounds a lot like what I heard as a child growing up in Alabama, where George Wallace was governor.

Where is civility?

If you say, "Good morning. How are you? Have a pleasant day," and then use your position to hurt others that is not civility; that is hypocrisy. Not cursing does not make one civil. If a man never says the S-word, but treats people like the S-word, he is a hypocrite and he makes my stomach hurt.

A man threw a cup from his car window, another parked in a "handicap zone," another stopped his car in the middle of the road to talk, another cut through a parking lot to avoid a traffic light, then yelled to a woman, "Hey, girl, gimme that sweater." I found road rage, horns blaring, middle fingers waving, fists flailing, criminal trial dates.

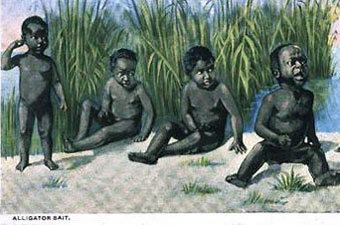

And then I found something. I lectured to Phil Middleton's class. I took his students to the Jim Crow Museum. I showed them the ugliness, the Mammy, the Sambo, the Picaninny, the caricatured sores foisted on us—the propaganda directed against us. I showed them. Showed it all. And we went deep, deeper than ever, deeper than I meant to go. After three hours they had left, all but two—a young black woman and a middle-aged white man. The woman sat, paralyzed, transfixed, and stunned before a picture of nude black children. At the bottom of the picture were these words, "Alligator Bait." She sat there, watching it, trying to understand the hands that made it, the mind that conceived it. She didn't say a word, but her eyes, her frown, the hand at her forehead all said, "Why, Sweet Jesus, why?"

This story is really about the white man. He stopped staring at the items and instead stared at me. He was crying, not a sob, a single tear stream. I wanted to say something, to be the teacher, the make-it-right teacher, you know, the master teacher. Before I could fix it, he said, "I am sorry, Mr. Pilgrim. Forgive me."

All the my years of collecting racist garbage I never realized how much I needed to hear some white person, any sincere white person, say, "I am sorry." Not because it was the politically right thing to say—the hell with that; and not because it seemed like the socially right thing to do, no, no, I needed a real apology, not a religious apology, nor a liberal one, just a real one, the kind of apology where both people know that they won't be the same afterward. I explained to him that he didn't make any of the objects; therefore he didn't owe me an apology.

On my way home I cried. It was the first time I cried about the objects in the Jim Crow Museum. It sounds corny but I cried like someone had died, like someone had been born: cleansed myself of other people's hatred with a stranger’s tears. And then I knew what civility was. Civility is treating others with respect, it is sharing pain, it is being broken, broken down, then put together again, not haughty, but humble servitude. Civility is more than "enduring others," it is this: "Whatsoever you would that others do unto you do that unto them."

Do me a favor, please before the cock crows again, tell someone, someone not me, that you are sorry, not about an abstraction, not about a deed done by others, but say you are sorry about something that you did, some wrong that you did. And when you say that you are sorry, please, mean it. Say it with a sincerity that changes two lives. That is civility. A commitment to social justice and social activism ought to begin with our everyday relationships.

The rooster crows at 6:33 tomorrow morning.

David Pilgrim

Curator, Jim Crow Museum

March 30, 2006

Edited 2019