Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

There is a direct and strong link between the word nigger and anti-black caricatures. Although nigger has been used to refer to any person of known African ancestry2 it is usually directed against black people who supposedly have certain negative characteristics. The Coon caricature, for example, portrays black men as lazy, ignorant, and obsessively self-indulgent; these are also traits historically represented by the word nigger. The Brute caricature depicts black men as angry, physically strong, animalistic, and prone to wanton violence. This depiction is also implied in the word nigger. The Tom and Mammy caricatures are often portrayed as kind, loving "friends" of white people. They are also presented as intellectually childlike, physically unattractive, and neglectful of their biological families. These latter traits have been associated with black people, generally, and are implied in the word nigger. The word nigger was a shorthand way of saying that black people possessed the moral, intellectual, social, and physical characteristics of the Coon, Brute, Tom, Mammy, and other racial caricatures.

The etymology of nigger is often traced to the Latin niger, meaning black. The Latin niger became the noun negro (black person) in English, and simply the color black in Spanish and Portuguese. In Early Modern French niger became negre and, later, negress (black woman) was clearly a part of lexical history. One can compare to negre the derogatory nigger – and earlier English variants such as negar, neegar, neger, and niggor – which developed into a parallel lexico-semantic reality in English. It is likely that nigger is a phonetic spelling of the white Southern mispronunciation of Negro. Whatever its origins, by the early 1800s it was firmly established as a denigrative epithet. Almost two centuries later, it remains a chief symbol of white racism.

The word nigger carries with it much of the hatred and repulsion directed toward Africans and African Americans. Historically, nigger defined, limited, and mocked African Americans. It was a term of exclusion, a verbal justification for discrimination. Whether used as a noun, verb, or adjective, it reinforced the stereotype of the lazy, stupid, dirty, worthless parasite. No other American ethnophaulism carried so much purposeful venom, as the following representative list suggests:

Nigger has been used to describe a dark shade of color (nigger-brown, nigger-black), the status of white people who interacted with black people (nigger-breaker, -dealer, -driver, -killer, -stealer, -worshipper, and -looking), and anything belonging to or associated with African Americans (nigger-baby, -boy, -girl, -mouth, -feet, -preacher, -job, -love, -culture, -college, -music, and so forth).4 Nigger is the ultimate American insult; it is used to offend other ethnic groups, as when Jews are called white-niggers; Arabs, sandniggers; or Japanese, yellow-niggers.

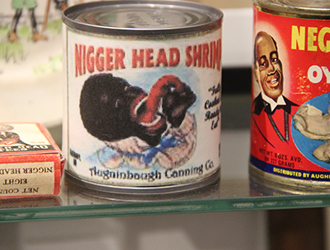

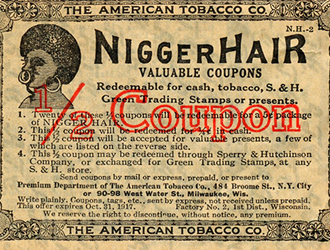

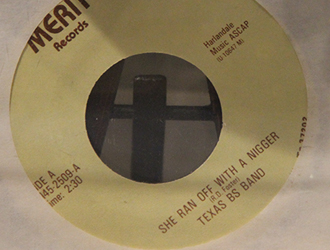

Both American slavery and the Jim Crow caste system which followed were undergirded by anti-black images. The negative portrayals of black people were both reflected in and shaped by everyday material objects: toys, postcards, ashtrays, detergent boxes, fishing lures, children's books. These items, and countless others, portrayed black people with bulging, darting eyes, fire-red and oversized lips, jet black skin, and either naked or poorly clothed. The majority of these objects did not use the word nigger; however, many did. In 1874, the McLoughlin Brothers of New York manufactured a puzzle game called "Chopped Up Niggers." Beginning in 1878, the B. Leidersdory Company of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, produced NiggerHair Smoking Tobacco - several decades later the name was changed to BiggerHair Smoking Tobacco. In 1917, the American Tobacco Company had a NiggerHair redemption promotion. NiggerHair coupons were redeemable for "cash, tobacco, S. & H. Green stamps, or presents."

A 1916 magazine advertisement, copyrighted by Morris & Bendien, showed a black child drinking ink. The caption read, "Nigger Milk."

The J. Millhoff Company of England produced a series of cards (circa 1930s), which were widely distributed in the United States. One of the cards shows ten small black dogs with the caption: "Ten Little Nigger Boys Went Out To Dine." This is the first line from the popular children's story The Ten Little Niggers.

Ten Little Nigger Boys went out to dine; One choked his little self, and then there

were Nine.

Nine Little Nigger Boys sat up very late; One overslept himself, and then there were

Eight.

Eight Little Nigger Boys traveling in Devon; One said he'd stay there, and then there

were Seven.

Seven Little Nigger Boys chopping up sticks; One chopped himself in halves, and then

there were Six.

Six Little Nigger Boys playing with a hive; A Bumble-Bee stung one, and then there

were Five.

Five Little Nigger Boys going in for Law; One got in Chancery, and then there were

Four.

Four Little Nigger Boys going out to Sea; A Red Herring swallowed one, and then there

were Three.

Three Little Nigger Boys walking in the Zoo; The big Bear hugged one, and then there

were Two.

Two Little Nigger Boys sitting in the Sun; One got frizzled up, and then there was

One.

One Little Nigger Boy living all alone; He got married, and then there were None.

(Jolly Jingles, n.d.)

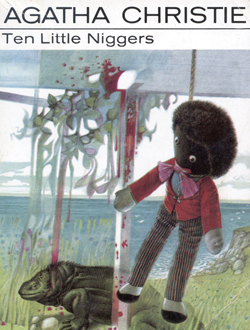

In 1939, Agatha Christie, the popular fiction writer, published a novel called Ten Little Niggers. Later editions sometimes changed the name to Ten Little Indians, or And Then There Were None, but as late as 1978, copies of the book with the original title were being produced

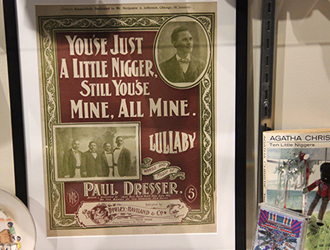

into the 1980s. It was not rare for sheet music produced in the first half of the

20th century to use the word nigger on the cover. The Howley, Haviland Company of New York, produced sheet music for

the songs "Hesitate Mr. Nigger, Hesitate," and "You'se Just A Little Nigger, Still

You'se Mine, All Mine." The latter was billed as a children's lullaby.

In 1939, Agatha Christie, the popular fiction writer, published a novel called Ten Little Niggers. Later editions sometimes changed the name to Ten Little Indians, or And Then There Were None, but as late as 1978, copies of the book with the original title were being produced

into the 1980s. It was not rare for sheet music produced in the first half of the

20th century to use the word nigger on the cover. The Howley, Haviland Company of New York, produced sheet music for

the songs "Hesitate Mr. Nigger, Hesitate," and "You'se Just A Little Nigger, Still

You'se Mine, All Mine." The latter was billed as a children's lullaby.

Some small towns used nigger in their names, for example, Nigger Run Fork, Virginia. Nigger was a common name for darkly colored pets, especially dogs, cats, and horses. So-called "Jolly Nigger Banks," first made in the 1800s, were widely distributed as late as the 1960s. Another common item - with many variants, produced on posters, postcards, and prints - is a picture of a dozen black children rushing for a swimming hole. The captions read, "Last One In's A Nigger."

One of the most interesting and perplexing phenomena in American speech is the use of nigger by African Americans. When used by black people, nigger refers to the following: all black people ("A nigger can't even get a break."); black men ("Sisters want niggers to work all day long."); black people who behave in a stereotypical, and sometimes mythical, manner ("He's a lazy, good-for-nothing nigger."); things ("This piece-of-shit car is such a nigger."); foes ("I'm sick and tired of those niggers bothering me!"); and friends ("Me and my niggers are tight.").

This final usage, as a term of endearment, is especially problematic. "Sup Niggah," has become an almost universal greeting among young urban black people. When pressed, black people who use nigger or its variants claim the following: it has to be understood contextually; continual use of the word by black people will make it less offensive; it is not really the same word because white people are saying nigger (and niggers) but black people are saying niggah (and niggaz); and, it is just a word and black people should not be prisoners of the past or the ugly words which originated in the past. These arguments are not convincing. Brother (Brotha) and Sister (Sistha or Sista) are terms of endearment. Nigger was and remains a term of derision. Moreover, the false dichotomy between black people or African Americans (respectable and middle-class) and niggers (disrespectable and lower class) should be opposed. No black people are niggers, irrespective of behavior, income, ambition, clothing, ability, morals, or skin color. Finally, if continued use of the word lessened its sting then nigger would by now have no sting. Black people, beginning in slavery, have internalized the negative images that white society cultivated and propagated about black skin and black people. This is reflected in periods of self- and same-race loathing. The use of the word nigger by black people reflects this loathing, even when the user is unaware of the psychological forces at play. Nigger is the ultimate expression of white racism and white superiority no matter how it is pronounced. It is a linguistic corruption, a corruption of civility. Nigger is the most infamous word in American culture. Some words carry more weight than others. At the risk of hyperbole, is genocide just another word? Pedophilia? Obviously, no: neither is nigger.

After a period of relative dormancy, the word nigger has been reborn in popular culture. It is hard-edged, streetwise, and it has crossed over into movies like Pulp Fiction (Bender & Tarantino, 1994) and Jackie Brown (Bender & Tarantino, 1997), where it became a symbol of "street authenticity" and hipness. Denzel Washington's character in Training Day (Newmyer, Silver & Fuqua, 2001) uses nigger frequently and harshly.

Richard Pryor long ago disavowed the use of the word in his comedy act, but Chris Rock and Chris Tucker, the new black male comedy kings, use nigger regularly - and not affectionately. Justin Driver (2001), a social critic, argued persuasively that both Rock and Tucker are modern minstrels - shucking, jiving, and grinning, in the tradition of Stepin Fetchit.

Poetry by African Americans is also instructive, as one finds nigger used in black poetry over and over again. Major and minor poets alike have used it, often with startling results: Imamu Amiri Baraka, one of the most gifted of our contemporary poets, uses nigger in one of his angriest poems, "I Don't Love You."

. . .and what was the world to the words of slick nigger fathers too depressed to explain why they could not appear to be men. (1969, p. 55)

One wonders: how are readers supposed to understand "nigger fathers"? Baraka's use of this imagery, regardless of his intention, reinforces the stereotype of the worthless, hedonistic Coon caricature. Ted Joans's use of nigger in "The Nice Colored Man" makes Baraka's comparatively harmless and innocent. Joans tells the story about how he came to write this unusual piece. He was, he says, asked to give a reading in London because he was a "nice colored man." Infuriated by the labels "nice" and "colored", Joans set down the quintessential truculent poem. While the poem should be read in its entirety, a few lines will suffice:

. . .Smart Black Nigger Smart Black Nigger Smart Black Nigger Smart Black Nigger Knife Carrying Nigger Gun Toting Nigger Military Nigger Clock Watching Nigger Poisoning Nigger Disgusting Nigger Black Ass Nigger. . . (Henderson, 1972, pp. 223-225)

This is the poem, with adjective upon adjective attached to the word nigger. The shocking reality is that many of these uses can be heard in contemporary American society. Herein lies part of the problem: the word nigger persists because it is used over and over again, even by the people it defames. Devorah Major, a poet and novelist, said, "It's hard for me to say what someone can or can't say, because I work with language all the time, and I don't want to be limited." Opal Palmer Adisa, a poet and professor, claims that the use of nigger or nigga is "the same as young people's obsession with cursing. A lot of their use of such language is an internalization of negativity about themselves" (Allen-Taylor, 1998).

Rap musicians, themselves poets, rap about niggers before mostly white audiences, some of whom see themselves as waggers (white niggers) and refer to one another as "my niggah." Snoop Doggy Dogg, in his single, "You Thought," raps, "Wanna grab a skinny nigha like Snoop Dogg/Cause you like it tall/and work it baby doll." Tupac Shakur (1991), one of the most talented and popular rap musicians, had a song called "Crooked Ass Nigga." The song's lyrics included, "Now I could be a crooked nigga too/When I'm rollin' with my crew/Watch what crooked niggers do/I got a nine millimeter Glock pistol/I'm ready to get with you at the tip of a whistle/So make your move and act like you wanna flip/I fired thirteen shots and popped another clip." Rap lyrics which debase women and glamorize violence reinforce the historical Brute caricature

Erdman Palmore (1962) researched ethnophaulisms and made the following observations: the number of ethnophaulisms used correlates positively with the amount of out-group prejudice; and ethnophaulisms express and support negative stereotypes about the most visible racial and cultural differences.

White supremacists have found the Internet an indispensable tool for spreading their message of hate. An Internet search of nigger locates many anti-black web pages: Niggers Must Die, Hang A Nigger For America, Nigger Joke Central, and literally thousands of others. Visitors to these sites know, like most black people know experientially, that nigger is an expression of anti-black antipathy. Is it surprising that nigger is the most commonly used racist slur during hate crimes?

No American minority group has been caricatured as often, in as many ways, as have black people. These caricatures combined distorted physical descriptions and negative cultural and behavior stereotypes. The Coon caricature, for example, was a tall, skinny, loose-jointed, dark-skinned male, often bald, with oversized, ruby-red lips. His clothing was either ragged and dirty or outlandishly gaudy. His slow, exaggerated gait suggested laziness. He was a pauper, lacking ambition and the skills necessary for upward social mobility. He was a buffoon. When frightened, the Coon's eyes bulged and darted. His speech was slurred, halted, and replete with malapropisms. His shrill, high-pitched voice made white people laugh. The Coon caricature dehumanized black people, and served as a justification for social, economic, and political discrimination.

Nigger may be viewed as an umbrella term - a way of saying that black people have the negative characteristics of the Coon, Buck, Tom, Mammy, Sambo, Picaninny, and other anti-black caricatures. Nigger, like the caricatures it encompasses and implies, belittles black people, and rationalizes their mistreatment. The use of the word or its variants by black people has not significantly lessened its sting. This is not surprising. The historical relationship between European Americans and African Americans was shaped by a racial hierarchy which spanned three centuries. Anti-black attitudes, values, and behavior were normative. Historically, nigger more than any word captured the personal antipathy and institutionalized racism directed toward black people. It still does.

© Dr. David Pilgrim, Professor of Sociology, and Dr. Phillip Middleton, Professor

of Languages and Literature,

Ferris State University.

Sept., 2001

Edited 2023

1 An earlier version of this paper, entitled "Purposeful Venom Revisited," was published in Matthews (1999, pp. 91-93). David Pilgrim is a sociologist; Phillip Middleton is a linguist.

2 Dictionaries typically defined nigger as a synonym for Negro, Black, or dark-skinned people. See, for example, Wentworth (1944, p. 412). Recent dictionaries are more likely to mention that nigger is a term of contempt. Please read Williams (2001).

3 Even innocent words - boy, girl, and uncle - took on racist meanings when applied to black people.

4 For a brief analysis of these terms see, Simpson (1989, pp. 401-405).

Allen-Taylor, J. D. (1998, April 9-15). New word order. Metro. Retrieved from http://www.metroactive.com/papers/metro/04.09.98/cover/nigger-9814.html.

Baraka, A. (1969). Black magic: Sabotage, Target study, Black art: Collected poetry, 1961-1967. 1969. New York, NY: Bobbs-Merrill.

Bender, L. (Producer), & Tarantino, Q. (Director). (1994). Pulp fiction [Motion picture]. United States: Miramax Films.

Bender, L. (Producer), & Tarantino, Q. (Director) (1997). Jackie Brown [Motion picture]. United States: Miramax Films.

Christie, A. (1982). Ten little niggers. Glasgow: Collins.

Driver, J. (2001, June 11). Black comedy's reactionary hipness: The mirth of a nation. The New Republic, 224, 29-33.

Ehrlich, H J. (1973). The social psychology of prejudice: A systematic theoretical review and propositional inventory of the American social psychological study of prejudice. New York, NY: Wiley.

Green, J. (1984). The dictionary of contemporary slang. New York, NY: Stein and Day.

Henderson, S. E. (1972). Understanding the new Black poetry: Black speech and Black music as poetic references. New York, NY: William Morrow and Company.

Jolly Jingles. (n.d.). Chicago, IL: M.A. Donohue & Company. Matthews, G. E. (Ed.) (1999). Journey towards nationalism: The implications of race and racism. New York, NY: Forbes.

Newmyer, R. F., & Silver, J. (Producers), & Fuqua, A. (Director). (2001). Training day [Motion picture]. United States: Warner Bros. Pictures.

Palmore, E. (1962, January). Ethnophaulisms and ethnocentrism. American Journal of Sociology 67, 442-445.

Schaefer, R. T. (2000). Racial and ethnic groups (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Shakur, T. (1991). Crooked ass nigga. Retrieved from http://lyrics.wikia.com/2Pac:Crooked_Ass_Nigga.

Simpson, J. A., & Weiner, E. S. C. (1989). The Oxford English dictionary. (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wentworth, H. (1944). American dialect dictionary. New York, NY: Thomas Y. Crowell Co.

Williams, C. M. (2001). Nigger. In Kim Pearson's dictionary of slurs. Retrieved from http://web.archive.org/web/20090223185954/http://kpearson.faculty.tcnj.edu/Dictionary/nigger.htm.