Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

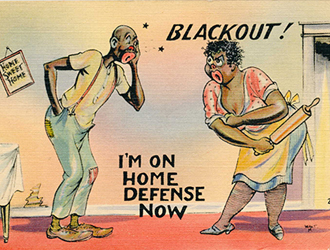

The Sapphire Caricature portrays black women as rude, loud, malicious, stubborn, and overbearing.1 This is the Angry Black Woman (ABW) popularized in the cinema and on television. She is tart-tongued and emasculating, one hand on a hip and the other pointing and jabbing (or arms akimbo), violently and rhythmically rocking her head, mocking African American men for offenses ranging from being unemployed to sexually pursuing white women. She is a shrill nagger with irrational states of anger and indignation and is often mean-spirited and abusive. Although African American men are her primary targets, she has venom for anyone who insults or disrespects her. The Sapphire's desire to dominate and her hyper-sensitivity to injustices make her a perpetual complainer, but she does not criticize to improve things; rather, she criticizes because she is unendingly bitter and wishes that unhappiness on others. The Sapphire Caricature is a harsh portrayal of African American women, but it is more than that; it is a social control mechanism that is employed to punish black women who violate the societal norms that encourage them to be passive, servile, non-threatening, and unseen.

From the 1800s through the mid-1900s, black women were often portrayed in popular culture as "Sassy Mammies" who ran their own homes with iron fists, including berating black husbands and children. These women were allowed, at least symbolically, to defy some racial norms. During the Jim Crow period, when real black people were often beaten, jailed, or killed for arguing with white people, fictional Mammies were allowed to pretend-chastise white people, including men. Their sassiness was supposed to indicate that they were accepted as members of the white family, and acceptance of that sassiness implied that slavery and segregation were not overly oppressive. A well-known example of a Sassy Mammy was Hattie McDaniel, a black actress who played feisty, quick-tempered mammies in many movies, including Judge Priest (Wurtzel & Ford, 1934), Music is Magic (Stone & Marshall, 1935), The Little Colonel (DeSylva & Butler, 1935), Alice Adams (Berman & Stevens, 1935), Saratoga (Hyman & Conway, 1937), The Mad Miss Manton (Wolfson & Jason, 1938), and Gone With the Wind (Selznick & Fleming, 1939). In these roles she was sassy (borderline impertinent) but always loyal. She was not a threat to the existing social order.

It was not until the Amos 'n' Andy radio show that the characterization of African American women as domineering, aggressive, and emasculating shrews became popularly associated with the name Sapphire. The show was conceived by Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, two white actors who portrayed the characters Amos Jones and Andy Brown by mimicking and mocking black behavior and dialect. At its best, Amos 'n' Andy was a situational comedy; at its worse, it was an auditory minstrel show.2 The show, with a mostly-white cast, aired on the radio from 1928 to 1960, with intermittent interruptions. The television version of the show, with network television's first all-black cast, aired on CBS from 1951-53, with syndicated reruns from 1954 to 1966. It was removed, in large part, through the efforts of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the civil rights movement. Both as a radio show3 and television show, Amos 'n' Andy was extremely popular, and this was unfortunate for African Americans because it popularized racial caricatures of black people. Americans learned that black people were comical, not as actors but as a race.

Amos 'n Andytold stories about the everyday foibles of the members of the Mystic Knights of the Sea, a black fraternal lodge. The lead characters were Amos Jones, a Harlem taxi driver and his gullible friend, Andy Brown. Starring in a nontitle lead role was the character George "Kingfish" Stevens, the leader of the lodge. Many of the stories revolved around Kingfish, a get-rich-quick schemer and a con artist who avoided work, and, when possible, took financial advantage of the ignorance and naivete of Andy and others (see, for example, the episode Kingfish Sells a Lot). Kingfish was the prototypical Coon, a lazy, easily confused, chronically unemployed, financially inept buffoon given to malapropisms. Kingfish was married to Sapphire Stevens who regularly berated him as a failure.

Kingfish represented the worst in racial stereotyping; there was little redemptive about the character. His ignorance was highlighted by his nonsensical misuse of words, for example, ""I deny the allegation, Your Honor, and I resents the alligator," or "I'se regusted." Kingfish was not a good thinker or speaker. Even worse, he was a crook without scruples. He was too lazy to work and not above exploiting his wife and friends.

In other words, he was a television embodiment of some of the unforgiving ideas that many Americans had about black men. Other characters, including Lightnin,' a Stepin Fetchit-like character on the show, had jobs and were honest, but Kingfish's worthlessness justified Sapphire's harsh critique of his life. It must be noted, that Sapphire Stevens directed her disgust at her husband; hers was not the generalized anger that is today associated with angry black women.

Sue Jewell (1993), a sociologist, opined that the Sapphire image necessitates the presence of an African American man; "It is the African American male that represents the point of contention, in an ongoing verbal dual between Sapphire and the African American male ... (His) lack of integrity and use of cunning and trickery provides her with an opportunity to emasculate him through her use of verbal put downs" (p. 45). In the all-black or mostly-black situational comedies that have appeared on television from the 1970s to the present, the Sapphire is a stock character. Like Sapphire Stevens, she demeans and belittles lazy, ignorant, or otherwise flawed black male characters.

Black people on television have been overrepresented in situational comedies and underrepresented in dramatic series; one problem with this imbalance is that black people in situational comedies are portrayed in racially stereotypical ways in order to get laughs. Canned laughter prompts the television audience to laugh as the angry black woman, the Sapphire, insults and mocks black males.

Aunt Esther (also called Aunt Anderson) was a Sapphire character on the television situational comedy Sanford and Son, which premiered on NBC in 1972, with a final episode in 1977, and is still running in syndication. She was the Bible-swinging, angry nemesis and sister-in-law of the main character, Fred. Theirs was a love-mostly hate relationship. Fred would call Aunt Esther ugly and she would call him a "fish-eyed fool," an "old sucka," or a "beady-eyed heathen." Then, they would threaten to hit each other. Aunt Esther dominated her husband Woodrow, a mild-mannered alcoholic. In this latter relationship, you have the idea of the aggressive black woman dominating a weak, morally defective black man.

The situational comedy Good Times aired between 1974 and 1979 on the CBS television network. The show followed the life of the Evans family in a Chicago housing project modeled on the infamous Cabrini-Green projects. This was one of the first times that a poor family had been highlighted in a weekly television series. Episodes of Good Times dealt with the Evans' attempts to survive despite living in suffocating poverty. There were several racial caricatures on the show, most notably the son, James Evans Jr. (also called J.J.), who devolved into a Coon-like minstrel. After the first season the episodes increasingly focused on J.J.'s stereotypically buffoonish behavior. Esther Rolle, the actress who played the role of Florida Evans, the mother, expressed her dislike for J.J.'s character in a 1975 interview with Ebony magazine: "He's eighteen and he doesn't work. He can't read or write. He doesn't think. The show didn't start out to be that...Little by little-with the help of the artist, I suppose, because they couldn't do that to me -- they have made J.J. more stupid and enlarged the role. Negative images have been slipped in on us through the character of the oldest child."("Bad Times" 1975) In black-themed situational comedies when there is a Coon character there is often a Sapphire character to mock him. In Good Times a character that bantered with and mocked J.J. was his sister, Thelma. A clearer example of a Sapphire, however, was the neighbor, Willona Woods, though she rarely targeted J.J. Instead, Willona belittled Nathan Bookman, the overweight superintendent, and she put down a series of worthless boyfriends, an ex-husband, politicians, and other men with questionable morals and work ethics.

In situational comedies with a primarily black cast, the black male does not have to be lazy, thick-witted, or financially unsuccessful for him to be taunted by a Sapphire character. The Jeffersons, which aired from 1975 to 1985, focused on an upper-middle class family that had climbed up from the working class -- in the show's theme song there is the line, "We finally got a piece of the pie." George and Louise Jefferson were making so much money from their dry-cleaning businesses that they hired a housekeeper, Florence Johnston. Her relationship with George was often antagonistic and the back-talking, wisecracking, housekeeper approximated a Sapphire. She often teased George about his short stature, balding head, and decisions.

Another example of a Sapphire was the character Pamela (Pam) James, who appeared on Martin, a situational comedy that aired from 1992 to 1997 on Fox. Pam was a badmouthed, wisecracking friend/foe of the lead character, Martin. Tichina Arnold, the actress who played Pam, plays Rochelle, a dominating, aggressive matriarch in the situational comedy, Everybody Hates Chris, which ran from 2005 to 2009, and is still aired on cable television. Arnold has mastered the role of the angry, black woman.

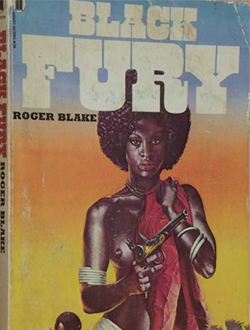

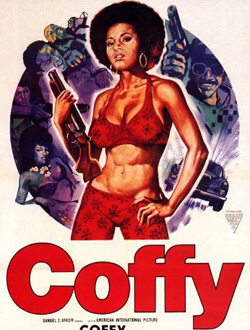

The film genre called blaxploitation emerged in the early 1970s. These movies, which targeted urban black audiences, exchanged one set of racial caricatures -- Mammy, Tom, Uncle, Picanninny -- for a new set of equally offensive racial caricatures -- Bucks (sex-crazed deviants) Brutes, (pimps, hit-men, and dope peddlers), and Nats (white people-haters). One old caricature, the Jezebel, was revamped. The portrayal of African American women as hyper-sexual temptresses was as old as American slavery, but during the blaxploitation period the Jezebel caricature and the Sapphire caricature merged into a hybrid: angry "whores" fighting injustice. Black actresses such as Pam Grier built careers starring in blaxploitation movies. Their characters resembled those of the black male superheroes: they were physically attractive and aggressive rebels, willing and able to use their bodies, brains, and guns to gain revenge against corrupt officials, drug dealers, and violent criminals. Their anger was not focused solely, or primarily, at black men; rather, it was focused at injustice and the perpetuators of injustice.

In the film Coffy (Papazian & Hill, 1973), Pam Grier (Coffy) plays a nurse by day and vigilante by night who conducts a brutal one-woman war on organized crime. In the movie, she pretends to be a "strung out whore" to get revenge on the drug dealers who got her little sister hooked on heroin. Coffy lures the culprits back to their room where she graphically shoots one in the head and gives the other a fatal dose of heroin. The remainder of the movie finds Coffy using guns and her body to punish King George, a flamboyant pimp, the sadistic mobster Arturo Vitroni, and every Mafioso and crooked cop who crosses her path.

Today, the Sapphire is one of the dominant portrayals of black woman. This is evident by the words of Cal Thomas, a commentator for FOX Television: "Look at the image of angry black women on television. Politically you have Maxine Waters of California, liberal Democrat. She's always angry every time she gets on television. Cynthia McKinney, another angry black woman. And who are the black women you see on the local news at night in cities all over the country. They're usually angry about something. They've had a son who has been shot in a drive-by shooting. They are angry at Bush. So you don't really have a profile of non-angry black women, of whom there are quite a few."("Transcript: Fox", 2008) Thomas, admittedly an untrained sociologist, expressed what many Americans see and internalize, namely, images of Sapphires: angry at black men, white men, white women, the federal government, racism, maybe life itself. Thomas, shortly after making his statements about black women, agreed with a co-panelist that Oprah Winfrey is not angry.

The portrayal of black women as angry Sapphires permeates this culture. A Google search of Angry Black Women or ABW will demonstrate how pervasive this caricature has become. She lives in most movies with an all-black or predominantly black cast. For example, there is Terri, cussing and insulting the "manhood" of black men in Barbershop (Brown, Teitel, Tillman & Story, 2002) and its sequel, Barbershop 2 (Gartner, Teitel, Tillman & Sullivan, 2004). There is the augmentative Angela in Why Did I Get Married (Cannon & Perry, 2007). The clip art description reads, "Royalty-free people clipart picture image of an angry african american woman in a purple dress and heels, standing with her arms crossed and tapping her foot with a stern expression on her face. She could be mad at her child, a colleague or husband." There are stock pictures of angry black women, such as those at www.gettyimages.com/photos/angry-black-woman. There are books devoted to angry black women, for example, The Angry Black Woman's Guide to Life (Millner, Burt-Murray, & Miller, 2004), and Web sites such as http://angryblackbitch.blogspot.com/where you can buy Angry Black Bitch cups, shirts, pillows, tile coasters, aprons, mouse pads, and Teddy Bears. There is even a pseudo-malady called, "Angry Black Woman Syndrome."

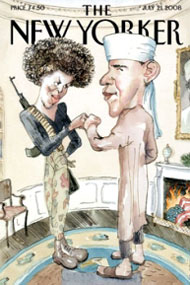

The tabloid talk shows that became popular in the 1990s: The Jerry Springer Show, The Jenny Jones Show, The Maury Povich Show, and The Ricki Lake Show, helped reinforce the racial stereotypes of African Americans, including the stereotype of black women as angry, castrating shrews. By the early 2000s, the "Trash Talk" shows had receded in popularity, in part because of the emergence of so-called "Reality Shows." Again, these shows served as vehicles for African American women to be portrayed as Sapphires. Vanessa E. Jones, from the Boston Globe, wrote of the Sapphire: "You see elements of her in Alicia Calaway of "Survivor: All-Stars," who indulged in a temperamental bout of finger wagging during an argument in 2001's "Survivor: The Australian Outback." Coral Smith, who rules with an iron tongue on MTV's "Real World/Road Rules Challenge: The Inferno," browbeat one female cast mate so badly a week ago that she challenged Smith to a fight. Then there's Omarosa Manigault-Stallworth of "The Apprentice," who rode the angry-black-woman stereotype to the covers of People and TV Guide magazines even as she made fellow African-American businesswomen wince."(Jones, 2004) Omarosa Manigault-Stallworth gained a great deal of national disdain and celebrity as a contestant on The Apprentice, Donald Trump's reality show. Manigault-Stallworth, who is almost always referred to by the single name Omarosa, was portrayed (and intentionally acted) as a cross between a Jezebel -- a hypersexual flirt and seductress -- and a bitter, aggressive Sapphire. Lorien Olive (2008), a political blogger, theorized on how white people saw Omarosa: "At least among white people, she was interpreted in various ways as conniving, lazy, selfish, a sham, overly-ambitious, uppity, ungrateful, and paranoid. I guess I was always less interested in whether Omarosa was actually any of those things or whether it was simply an effect of the distortion of the editing of reality television. I was more interested in the fact that Omarosa seemed to stand for something bigger in the eyes of many white people. Her constant accusations of racism directed toward her fellow contestants and the fact that she wore her alienation and distrust of her team-mates on her sleeve opened up a whole world of racial speculation and ridicule. I would say debate, but in all of my internet travels, I haven't found much of anyone who wanted to go out on a limb for Omarosa. The fact that so many white people felt justified in their hatred for Omarosa (a hatred that could be passed of as a benign over-investment in a guilty pleasure: a reality TV series) is telling. She became the symbol of everything that went wrong in the post-Civil Rights Era: paranoid "reverse racism"; the ungrateful and undeserving product of affirmative action; the "uppity" Black person who puts on airs; the beautiful, hyper-sexualized Black woman who pulled the wool over the powerful white man's eyes." Olive next makes a connection that many others are making on Internet sites, namely, that First Lady Michelle Obama is the new Omarosa: a bitter, selfish, uppity, ungrateful, overly-ambitious Sapphire. One of the derisive nicknames for Michelle Obama is "Omarosa Obama." This demonstrates how the Sapphire caricature has broadened from an emasculating hater of black men to a bitter woman who hates anyone who displeases her.

Sociologists often speak of how dominant groups praise a behavior when done by its members, but criticize a minority group for demonstrating that behavior. To use sociological jargon, this is an example of an in-group virtue becoming an out-group vice. According to the blogger abagond (2008), "Where white women are said to be 'independent,' black women are said to be 'emasculating,' robbing their men of their sense of manhood. Where white women are said to be standing up for themselves, black women are seen as wanting a fight. And so on. The same actions are read differently." Being an articulate foe of injustice may be seen as a praise-worthy trait among white people; however, black women with similar traits may be seen as bitter, selfish complainers.

Michelle Obama challenges the scripts that many Americans have for African American women. She is the antithesis of the Mammy caricature. The traditional portrayal of Mammy looked something like this: an obedient, loyal domestic servant, who cared more for the family members of her employer than she did for her own family; overweight and desexualized; and, most important to the portrait: not a threat to the social order. Michelle Obama is a Harvard-trained attorney, a conscientious mother, physically attractive, and she critiques and challenges the culture. She also does not fit the Jezebel image or its modern variant: the butt-shaking Hoogie Mama -- though FOX News tried to imply this when they referred to her in text as Senator Obama's "Baby Mama." Michelle Obama is not a Tragic Mulatto; she is a dark-skinned woman actively involved in civil rights and community activism. The so-called Tragic Mulatto was ashamed of her African heritage; Michelle Obama embraces her African American heritage and expresses her dissatisfaction with racial injustice.

So, if she does not fit one of the three dominant historical caricatures of African American women, what imagery is left? Ideally, she would be judged on her individual traits and not as a one-dimensional stereotype; however, there is little ideal about patterns of race relations in this country. Racial stereotyping, too often, is a convenient way to pigeonhole others into categories that make sense to us. Instead of allowing Michelle Obama to be central to a new cultural narrative of black women (and the black family) there is a growing tendency to view Michelle Obama's words and behaviors as examples of the black woman as Sapphire. When she said, while speaking at a Milwaukee, Wisconsin political rally, "for the first time in my adult life I am proud of my country because it feels like hope is finally making a comeback," she was accused of being an unpatriotic, ungrateful, and angry radical. In this portrait, she is more Pam Grier (sans the gun and the hypersexuality) than Sapphire Stevens; her supposed bitterness and hatred are directed toward her country -- and implicitly its white citizens -- and not toward black men. Finally, there was a label to stick to her. According to Erin Aubry Kaplan (2008), a journalist and blogger:> "It's worth noting how Michelle was admired as long as she filled the prescription of a successful black woman on paper -- college grad, married to an equally successful black man, a working but attentive mother, financially secure, immaculately turned out. But as soon as she began revealing herself as a person and airing her views a bit, she began shape-shifting in the public eye into another kind of black woman altogether: angry, obstinate, mouthy -- a stereotypical harpy lurking in all black women that a friend of mine calls 'Serpentina.' The consternation about Michelle suggested an old racist sentiment that you can take the girl out of the ghetto, but you can never take the ghetto out of the girl." Sean Hannity, Bill O'Reilly, Rush Limbaugh, Laura Ingraham and other conservative talkshow hosts rushed to paint her as the ultimate angry black woman, and they wondered aloud what she had to be angry about. Not all the lambasting came from white Americans. Mychal Massie (2008), chairman of the National Leadership Network of Black Conservatives-Project 21 -- a conservative black think tank, said: "I find it reprehensible that those like herself and her husband, being devoid of credible positions, are able only to blame America and castigate its citizens. And that is exactly what Michelle Obama did -- with one sentence, she attacked every American, regardless of party affiliation when she uttered those profane words...Many Americans contribute to the Obamas' extravagant lifestyle. From those who clean their floors to those who sweep their sidewalks. Her comments reveal ingratitude and were an insult to millions of hardworking Americans and legal immigrants who appreciate the freedom and opportunity America offers. This country has made it possible for Michelle Obama to enjoy every privilege she and her family enjoy. Compared to the eloquent grace of Jackie Kennedy, Nancy Reagan, Barbara Bush and yes, even Rosalind Carter, she portrays herself as just another angry black harridan who spits in the face of the nation that made her rich, famous and prestigious." Central to these "critiques" of Michelle Obama is the couched argument that a person who is a successful attorney and administrator living in a nice home has forfeited the right to talk about injustice and inequality. This argument is short-sighted and flawed. It implies that only poor people have the right to express concerns about poverty, only the sick and diseased have a right to complain about inadequate health care, only a victim of crime has the right to complain about high crime rates, and so forth. The day that the privileged in this country -- and that includes Sean Hannity, Bill O'Reilly, Rush Limbaugh, Laura Ingraham, Mychal Massie, and Michelle Obama -- are as disgusted with injustice and equality as is the poor black or brown or white single mother in Detroit, Michigan, is the day this country takes a living step toward realizing its potential as the "city on the top of the hill." Critiquing America is not the same as hating America.

How does her saying, "for the first time in my adult life I am proud of my country because it feels like hope is finally making a comeback," validate Massie's claim that Michelle Obama is "another black harridan?" A harridan is a "scolding (even vicious) old woman" ("Harridan", n.d.). Calling someone a harridan for expressing an opinion is an ad hominem argument that tries to dismiss the substance of their opinion. Members of society who express unpopular opinions are often dismissed with personal attacks.

Newt Gingrich and the Republican Party rode the anger of white men into political dominance in 1994. What were they angry about? Affirmative action? Multiculturalism? Liberalism? Few people, especially members of the dominant group, questioned whether white men had the right to be angry. After Senator Hillary Clinton lost her bid for the 2008 Democratic Presidential nomination, a great deal of media attention was given to Angry White Women, so angry they threatened to vote for the Republican candidate. Some of their anger was fueled by disappointment; that happens in every political campaign. Others were angry because Senator Clinton's campaign symbolized, for them, the struggles and promise of being women in this culture. Some were angry about the sexist slurs, both thinly-veiled and obvious and gross, that were directed against Senator Clinton. These angry white women had many reasons to be angry, but the point here is that their right to be angry was rarely questioned. However, when a strong-minded, high profile black woman expresses even a hint of displeasure at injustice in this culture she is treated like a non-patriotic, ungrateful Sapphire. The black woman who expresses anything short of a patriotism that borders on chauvinism is condemned.

With people of color, in this case black women, there is a tendency for labels to become enduring stereotypes. The Sapphire portrayal has been around for as long as black women have dared to critique their lives and treatment. Sojourner Truth was seen and treated as a Sapphire, as were Ida Bell Wells-Barnett, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Josephine Baker, Shirley Chisholm, Anita Hill, Alice Walker, Rita Dove, and bell hooks. But the Sapphire label has not been restricted to abolitionists, anti-lynching crusaders, civil rights activists, politicians, and black feminists/womanists. Black women executives who voice disapproval at company policies run the risk of being seen as Sapphires, especially when the policies involve race and race relations. Young African American women who show displeasure at being treated as potential thieves when they shop are treated as Sapphires. The black woman who expresses bitterness or rage about her mistreatment in intimate relationships is often seen as a Sapphire; indeed, black women who express any dissatisfaction and displeasure, especially if they express the discontentment with passion, are seen and treated as Sapphires. The Sapphire name is slur, insult, and a label designed to silence dissent and critique.

© Dr. David Pilgrim, Professor of Sociology

Ferris State University

August, 2008

Edited 2023

1 In Yarbrough, M. with Bennett, C. (2000), the authors use these words to describe the Sapphire, "evil, bitchy, stubborn and hateful."

2Here is an example from the episode, 1930. I'se Regusted [Radio series episode]. In Amos 'n' Andy. Victor 22393. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H_yIba70Xz4&feature=related (episode starts at approximately the 2:00 minute mark).

3 The peak of the show's popularity was 1930-31, when it attracted an audience of between 30 and 40 million people a night, six nights a week -- representing an astounding a third of the entire population of the United States.

Abagond (2008, March 7). The Sapphire stereotype. Abagond. Retrieved from http://abagond.wordpress.com/2008/03/07/the-sapphire-stereotype/.

Bad times on the Good Times set. (1975, September). Ebony.

Berman, P. S. (Producer), & Stevens, G. (Director). (1935). Alice Adams. [Motion picture]. United States: RKO Radio Pictures.

Brown, M., Teitel, R., & Tillman, G. Jr. (Producers), & Story, T. (Director). (2002). Barbershop [Motion picture]. United States: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Cannon, R., & Perry, T. (Producers), & Perry, T. (Director). (2007). Why did I get married? [Motion picture]. United States; Lions Gate Films.

DeSylva, B. G. (Producer), & Butler, D. (Director). (1935). The little Colonel [Motion picture]. United States: Fox Film Corporation.

Gartner, A., Teitel, R., & Tillman, G. Jr. (Producers), & Sullivan, K. R. (Director). (2004). Barbershop 2: Back in business [Motion picture]. United States: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Harridan. (n.d.). In The free dictionary. Retrieved from http://www.thefreedictionary.com/harridan.

Hyman, B. H. (Producer), & Conway, J. (Director). (1937). Saratoga [Motion picture]. United States: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Jewell, K. S. (1993). From mammy to Miss America and beyond: Cultural images and the shaping of US social policy. New York, NY: Routledge.

Jones, V. E. (2004, April 20). The angry black woman: Tart-tongued or driven and no-nonsense, she is a stereotype that amuses some and offends others. The Boston Globe. Retrieved from http://www.boston.com/news/globe/living/articles/2004/04/20/the_angry_black_woman (fee required).

Kaplan, E.A. (2008, June 24). Who's afraid of Michelle Obama? Salon. Retrieved from http://www.salon.com/mwt/feature/2008/06/24/michelle_obama/index.html.

Massie, M. (2008, February 26). Michelle Obama: Angry black harridan. WND commentary. Retrieved from http://www.worldnetdaily.com/index.php?fa=PAGE.view&pageId=57312.

Millner, D., Burt-Murray, A., & Miller, M. (2004). The angry black woman's guide to life. New York, NY: Plume.

Olive, L. (2008, April 15). Omarosa Obama: Sapphire lives. Roadkill politics: A white working class perspective on politics.

Papazian, R. (Producer), & Hill, J. (Director). (1973). Coffy [Motion picture]. United States: American International Pictures.

Selznick, D. O. (Producer), & Fleming, V. (Director). (1939). Gone with the wind [Motion picture]. United States: Selznick International Pictures.

Stone, J. (Associate Producer), & Marshall, G. (Director). (1935). Music is magic [Motion picture]. United States: Fox Film Corporation.

Transcript: 'Fox News Watch'. (2008, June 14). Retrieved from http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,367601,00.html.

Wolfson, P. J. (Associate Producer), & Jason, L. (Director). (1938). The mad Miss Manton [Motion picture]. United States: RKO Radio Pictures. Wurtzel, S. M. (Producer), & Ford, J. (Director). (1934). Judge Priest [Motion picture]. United States: Fox Film Corporation.

Yarbrough, M. with Bennett, C. (2000). Cassandra and the 'Sistahs': The peculiar treatment of African American women in the myth of women as liars. Journal of Gender, Race and Justice, Spring 2000, 626-657.