Jim Crow Museum

1010 Campus Drive

Big Rapids, MI 49307

[email protected]

(231) 591-5873

The picaninny1 was the dominant racial caricature of black children for most of this country's history. They were "child coons," miniature versions of Stepin Fetchit (see Pilgrim (2000)). Picaninnies had bulging eyes, unkempt hair, red lips, and wide mouths into which they stuffed huge slices of watermelon. They were themselves tasty morsels for alligators. They were routinely shown on postcards, posters, and other ephemera being chased or eaten. Picaninnies were portrayed as nameless, shiftless natural buffoons running from alligators and toward fried chicken.

The first famous picaninny was Topsy -- a poorly dressed, disreputable, neglected enslaved girl. Topsy appeared in Harriet Beecher Stowe's anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. Topsy was created to show the evils of slavery. Here was an untamable "wild child" who had been indelibly corrupted by slavery.

She was one of the blackest of her race; and her round, shining eyes, glittering as glass beads, moved with quick and restless glances over everything in the room. Her mouth half open with astonishment at the wonders of the new Mas'r's parlor, displayed a white and brilliant set of teeth. Her woolly hair was braided in sundry little tails, which stuck out in every direction. The expression of her face was an odd mixture of shrewdness and cunning, over which was oddly drawn, like a veil, an expression of the most doleful gravity and solemnity. She was dressed in a single filthy, ragged garment, made of bagging; and stood with her hands demurely folded in front of her. Altogether, there was something odd and goblin-like about her appearance -- something as Miss Ophelia afterwards said, "so heathenish..." (p. 258)

Stowe hoped that readers would be heartbroken by the tribulations of Topsy, and would help end slavery -- which, she believed, produced many similar children. Her book, while leading some Americans to question the morality of slavery, was used by others to trivialize slavery's brutality. Topsy, for example, was soon a staple character in minstrel shows. The stage Topsy, unlike Stowe's version, was a happy, mirthful character who reveled in her misfortune. Topsy was still dirty, with kinky hair and ragged clothes, but these traits were transformed into comic props--as was her misuse of the English language. No longer a sympathetic figure, Topsy became, simply, a harmless coon. The stage Topsy and her imitators remained popular from the early 1850s well into the twentieth century (Turner, 1994, p. 14).

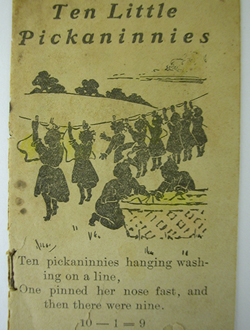

Black children were some of the earliest "stars" of the fledgling motion picture industry; albeit, as picaninnies (Bogle, 1994, p. 7). Thomas Alva Edison patented 1,093 inventions. In 1891 he invented the kinetoscope and the kinetograph, which laid the groundwork for modern motion picture technology. During his camera experiments in 1893, Edison photographed some black children as "interesting side effects." In 1904 he presented Ten Picaninnies, which showed those "side effects" running and playing. These nameless children were referred to as inky kids, smoky kids, black lambs, snowballs, chubbie ebonies, bad chillun, and coons.

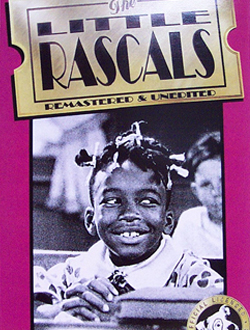

The Ten Picaninnies was a forerunner to Hal Roach's Our Gang series -- sometimes referred to as The Little Rascals. First produced in 1922, Our Gang continued into the "talkie era." Roach described the show as "comedies of child life." It included an interracial cast of children, including, at various times, these black characters: Sunshine Sammy, Pineapple, and Farina in the 1920s, and later, Stymie and Buckwheat. One or two black children appeared in each short episode.

Our Gang is often credited with being "one of Hollywood's few attempts...to do better by the Negro" (Leab, 1976, p. 46). All of the children, black and white, took turns playing nitwits. Donald Bogle (1994) wrote: "Indeed, the charming sense of Our Gang was that all of the children were buffoons, forever in scraps and scrapes, forever plagued by setbacks and sidetracks as they set out to have fun, and everyone had his turn at being outwitted" (p. 23). While this is true, the black characters were often buffoons in racially stereotypical ways. They spoke in dialect -- dis, dat, I is, you is, and we is. Farina, arguably the most famous picaninny of the 1920s, was on more than one occasion shown savagely eating watermelon or chicken. He was also terrified of ghosts -- this fear was a persistent theme for adult coons in later comedy films. Farina and Buckwheat wore tightly twisted "picaninny pigtails" and old patched gingham clothes which made their sex ambiguous. Why was this sexual ambiguity a necessary part of the show? Buckwheat, the quiet boy with big eyes, has an unenviable distinction: his name is now synonymous with picaninny. This is due, in large part, to Eddie Murphy's depiction of Buckwheat on Saturday Night Live in the 1980s. Indeed, the term picaninny is today rarely used as a racial slur; it has been replaced by the term buckwheat.

The picaninny caricature shows black children as either poorly dressed, wearing ragged, torn, old and oversized clothes, or, and worse, they are shown as nude or near-nude. This nudity suggests that black children, and by extension black parents, are not concerned with modesty. The nudity also implies that black parents neglect their children. A loving parent would provide clothing. The nudity of black children suggests that black people are less civilized than whites (who wear clothes).

The nudity is also problematic because it sexualizes these children. Black children are shown with exposed genitalia and buttocks -- often without apparent shame. Moreover, the buttocks are often exaggerated in size, that is, black children are shown with the buttocks of adults. The widespread depictions of nudity among black children normalizes their sexual objectification, and, by extension, justifies the sexual abuse of these children.

A disproportionately high number of African American children are poor, but the picaninny caricature suggests that all black children are impoverished. This poverty is evidenced by their ragged clothes. The children are hungry, therefore, they steal chickens and watermelon. Like wild animals, the picaninnies often must fend for themselves.

Picaninnies are portrayed in greeting cards, on-stage, and in physical objects as

insignificant beings. Stories like Ten Little Niggers show Black children being rolled over by boulders, chased by alligators, and set

on fire. Black children are shown on postcards being attacked by dogs, chickens, pigs

and other animals. This is consistent with the many 19th and 20th century pseudo-scientific

theories which claimed that black people were destined for extinction. William Smith,

a Tulane University professor, published The Color Line in 1905. He argued that black people would die off because the "doom that awaits

the Negro has been prepared in like measure for all inferior races" (Fredrickson,

1971, p. 257). George Fredrickson's The Black Image in the White Mind includes an excellent discussion of  the "black race will die" theories (pp. 71-164).

the "black race will die" theories (pp. 71-164).

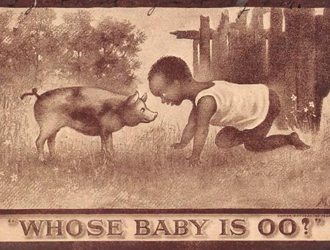

Picaninnies were often depicted side by side with animals. For example, a 1907 postcard, showed a Black child on his knees looking at a pig. The caption read, "Whose Baby is OO?" A 1930s bisque match holder showed a black baby emerging from an egg while a rooster looked on. On postcards black children were often referred to as coons, monkeys, crows, and opossums. A 1930s pinback2 showed a bird with the head of a black girl. Picaninnies were "shown crawling on the ground, climbing trees, straddled over logs, or in other ways assuming animal-like postures" (Turner, p. 15). The message was this: black children are more animal than human.

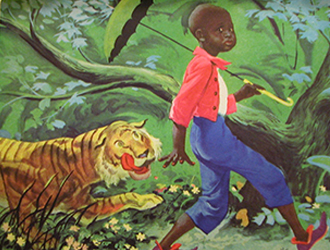

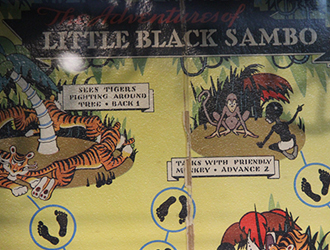

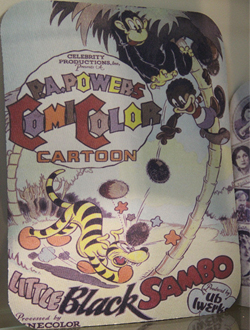

Arguably, the most controversial picaninny image is the one created by Helen Bannerman. Born Brodie Cowie Watson, the daughter of a Scottish minister, she married Will Bannerman, a surgeon in the British Army of India. She spent thirty years of her life in India. She regularly wrote illustrated letters with fantasy storylines to entertain their children. In 1898 there "came into her head, evolved by the moving of a train," the entertaining story of a little black boy, beautifully clothed, who outwits a succession of tigers, and not only saves his own life but gets a stack of tiger-striped pancakes (Bader, 1996, p. 536). The story eventually became Little Black Sambo. The book appeared in England in 1899 and was an immediate success. The next year it was published in the United States by Frederick A. Stokes, a mainstream publisher. It was even more successful than it had been in England. The book's success led to many imitators -- and controversies. Barbara Bader (1996), a book critic, summarized the events.

All American children did not see the same book, however. Though the authorized Stokes edition sold well and never went out of print, a host of other versions quickly began to appear from mass-market publishers, from reprint houses, from small, outlying firms unconstrained by the mutual courtesies of the major publishers. A few are straight knock-offs of the book that Bannerman made, without her name on the title page; the majority were reillustrated -- with gross, degrading caricatures that set Sambo down on the old plantation or, with equal distortiveness, deposited him in Darkest Africa. Libraries stocked the Stokes edition, and a few others selectively. But overall the bootleg Sambos were much cheaper, more widely distributed, and vastly more numerous.(pp. 537-538)

The illustrations were racially offensive, and so was the name Sambo. At the time that the book was originally published Sambo was an established anti-black epithet, a generic degrading reference. It symbolized the lazy, grinning, docile, childlike, good-for-little servant. Maybe Bannerman was unfamiliar with Sambo's American meaning. For many African Americans Little Black Sambo was an entertaining story ruined by racist pictures and racist names. Julius Lester (1997), who has recently co-authored Sam and the Tigers (Lester, Bannerman, Pinkney, & Bierhorst, 1996), an updated Afrocentric version of Little Black Sambo, wrote:

When I read Little Black Sambo as a child, I had no choice but to identify with him because I am black and so was he. Even as I sit here and write the feelings of shame, embarrassment and hurt come back. And there was a bit of confusion because I liked the story and I especially liked all those pancakes, but the illustrations exaggerated the racial features society had made it clear to me represented my racial inferiority -- the black, black skin, the eyes shining white, the red protruding lips. I did not feel good about myself as a black child looking at those pictures.

It is likely that Bannerman did not intentionally write Little Black Sambo to offend any group; after all, the story was conceived as a private fantasy tale to share with her children. It is also likely that she did not understand the racist overtones of the book. She tried to write an "exotic" tale. The book reflects, but does not exceed, the prevailing anti-black imaging of her time. Nevertheless, illustrations in Little Black Sambo are caricatures. She also depicted dark-skinned people in caricature form in her other books, including, Little Black Mingo (1902) and Little Black Quibba (1902). She used realistic, non-caricatured drawings of white characters in her books such as Pat and the Spider (1904), and Little White Squibba (1966).

Little Black Sambo served as the boiler plate for a spate of other versions, many of which used mean-spirited racist drawings and dialogue. The vulgar reprint versions were symbolic of black-white relations. Little Black Sambo's popularity coincided with the crystallization of Jim Crow laws and etiquette. Black people were denied basic human and civil rights, discriminated against in the labor market, barred from many public schools and libraries, harassed at voting booths, subjected to physical violence, and generally treated as second class citizens. The year that Little Black Sambo came to America a white-initiated race riot occurred in New Orleans. It was effectively a pogrom -- black people were beaten, their schools and homes destroyed. Little Black Sambo did not, of course, cause riots, but it entered America during a period of strained and harsh race relations. It was, simply, another insult in the daily lives of African Americans.

The anti-Little Black Sambo movement started in the 1930s and continued into the 1970s. Black educators and civil rights leaders organized numerous campaigns to get the book banned from public libraries, especially in elementary schools. In 1932 Langston Hughes said Little Black Sambo exemplified the "pickaninny variety" of storybook, "amusing undoubtedly to the white child, but like an unkind word to one who has known too many hurts to enjoy the additional pain of being laughed at" (Von Drasek, 2009). In the 1940s and 1950s the book was dropped from many lists of "Recommended Books." By the 1960s the book was seen as a remnant of a racist past.

Little Black Sambo was again popular by the mid-1990s. Its recent popularity is a result of many factors, including a white backlash against perceived political correctness. This is evident in internet discussions. Americans, black and white, are rereading the original book (and some of the unauthorized reprints). There is agreement that Bannerman's book is entertaining. However, there is little agreement regarding whether it is racist. White readers tend to focus on Bannerman's non-racist intentions and the unfairness of judging yesterday's "classics" by today's standards of racial equality. Black people find the book's title and the illustrations offensive. Most of the debate centers on Bannerman's version; there is no debating the racism explicit in later editions of the book produced by other writers and publishers.

In 1996 two readaptions of Little Black Sambo were published. The Story of Little Babaji, by Fred Marcellino (Bannerman & Marcellino), set the story in India, not Africa.

Also, the characters' names were changed to Babaji, Mamaji, and Papaji. It used the

Bannerman text but Marcellino drew non-caricatured illustrations. The book is uncontroversial.

Sam and the Tigers (Lester et al.), written by Julius Lester and illustrated by Jerry Pinkney, is a

retelling of the story in a folksy, southern black voice. The story's setting is not

Africa or India, but a mythical southern town "where the animals and the people lived

and worked together like they didn't know they weren't supposed to." There are still

tigers that Sam must outwit, but Lester's tale is contemporary. For example, after

one tiger threatens to eat him, Sam says, "If you do it'll send your cholesterol way

up." If Bannerman had used different names for the book and characters, and had used

realistic, not caricatured, illustrations, there would be little need for the Marcellino

or Lester adaptations.

© Dr. David Pilgrim, Professor of Sociology

Ferris State University

Oct., 2000

Edited 2024

1 It is also spelled pickaninny and piccaninny.

2A pinback is similar to a brooch, but it has a flat face to display an advertisement or other image.

Bader, B. (1996, September-October). Sambo, Babaji, and Sam. The Horn Book Magazine 72 (5), 536-547.

Bannerman, H. (1904). Pat and the spider: The biter bit. London: James Nisbet & Co.

Bannerman, H. (1902). The story of little black Mingo. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co.

Bannerman, H. (1902). The story of little black Quibba. London: James Nisbet & Co.

Bannerman, H. (1900). The story of little black Sambo. New York: F. A. Stokes.

Bannerman, H. (1966). The story of little white Squibba. London: Chatto & Windus.

Bannerman, H., & Marcellino, F. (1996). The story of little Babaji. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers.

Bogle, D. (1994). Toms, coons, mulattoes, mammies, and bucks: An interpretive history of Blacks in American films (New 3rd ed.). New York, NY: Continuum.

Fredrickson, G. M. (1971). The black image in the white mind: The debate on Afro-American character and destiny, 1817-1914. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Leab, D. J. (1975/1976). From Sambo to Superspade: The black experience in motion pictures. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co.

Lester, J., Bannerman, H., Pinkney, J., & Bierhorst, J. B. (1996). Sam and the tigers: A new telling of Little Black Sambo. New York, NY: Dial Books for Young Readers.

Lester, J. (1997). Little Black Sambo discussion from Child-Lit Listserv in November, 1997. Retrieved from http://ruby.fgcu.edu/courses/spillman/sambo.htm.

Pilgrim, D. (2000). The coon caricature. Retrieved from https://ferris.edu/jimcrow/coon/.

Selznick, D. O. (Producer), & Fleming, V. (Director). (1939). Gone with the wind [Motion picture]. United States: Selznick International Pictures.

Smith, W. B. (1905). The color line: a brief in behalf of the unborn. New York, NY: McClure, Phillips & Co.

Stowe, H.B. (1966). Uncle Tom's Cabin. New York, NY: New American Library.

Turner, P.A. (1994). Ceramic uncles & celluloid mammies: Black images and their influence on culture. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Von Drasek, L. (2009, February 13). Picturing Langston Hughes. Barnes and Noble Review. Retrieved from http://bnreview.barnesandnoble.com/t5/Reviews-Essays/Picturing-Langston-Hughes/ba-p/907.